Plasmablastic lymphoma

Haematolymphoid Tumours (WHO Classification, 5th ed.)

| This page is under construction |

editContent Update To WHO 5th Edition Classification Is In Process; Content Below is Based on WHO 4th Edition ClassificationThis page was converted to the new template on 2023-12-07. The original page can be found at HAEM4:Plasmablastic Lymphoma.

(General Instructions – The focus of these pages is the clinically significant genetic alterations in each disease type. This is based on up-to-date knowledge from multiple resources such as PubMed and the WHO classification books. The CCGA is meant to be a supplemental resource to the WHO classification books; the CCGA captures in a continually updated wiki-stye manner the current genetics/genomics knowledge of each disease, which evolves more rapidly than books can be revised and published. If the same disease is described in multiple WHO classification books, the genetics-related information for that disease will be consolidated into a single main page that has this template (other pages would only contain a link to this main page). Use HUGO-approved gene names and symbols (italicized when appropriate), HGVS-based nomenclature for variants, as well as generic names of drugs and testing platforms or assays if applicable. Please complete tables whenever possible and do not delete them (add N/A if not applicable in the table and delete the examples); to add (or move) a row or column in a table, click nearby within the table and select the > symbol that appears. Please do not delete or alter the section headings. The use of bullet points alongside short blocks of text rather than only large paragraphs is encouraged. Additional instructions below in italicized blue text should not be included in the final page content. Please also see Author_Instructions and FAQs as well as contact your Associate Editor or Technical Support.)

Primary Author(s)*

Mark Evans, MD (University of California, Irvine)

Fabiola Quintero-Rivera, MD (University of California, Irvine)

WHO Classification of Disease

| Structure | Disease |

|---|---|

| Book | Haematolymphoid Tumours (5th ed.) |

| Category | B-cell lymphoid proliferations and lymphomas |

| Family | Mature B-cell neoplasms |

| Type | Large B-cell lymphomas |

| Subtype(s) | Plasmablastic lymphoma |

WHO Essential and Desirable Genetic Diagnostic Criteria

(Instructions: The table will have the diagnostic criteria from the WHO book autocompleted; remove any non-genetics related criteria. If applicable, add text about other classification systems that define this entity and specify how the genetics-related criteria differ.)

| WHO Essential Criteria (Genetics)* | |

| WHO Desirable Criteria (Genetics)* | |

| Other Classification |

*Note: These are only the genetic/genomic criteria. Additional diagnostic criteria can be found in the WHO Classification of Tumours.

Related Terminology

(Instructions: The table will have the related terminology from the WHO autocompleted.)

| Acceptable | |

| Not Recommended |

Gene Rearrangements

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: Details on clinical significance such as prognosis and other important information can be provided in the notes section. Please include references throughout the table. Do not delete the table.)

| Driver Gene | Fusion(s) and Common Partner Genes | Molecular Pathogenesis | Typical Chromosomal Alteration(s) | Prevalence -Common >20%, Recurrent 5-20% or Rare <5% (Disease) | Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Significance - D, P, T | Established Clinical Significance Per Guidelines - Yes or No (Source) | Clinical Relevance Details/Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE: ABL1 | EXAMPLE: BCR::ABL1 | EXAMPLE: The pathogenic derivative is the der(22) resulting in fusion of 5’ BCR and 3’ABL1. | EXAMPLE: t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) | EXAMPLE: Common (CML) | EXAMPLE: D, P, T | EXAMPLE: Yes (WHO, NCCN) | EXAMPLE:

The t(9;22) is diagnostic of CML in the appropriate morphology and clinical context (add reference). This fusion is responsive to targeted therapy such as Imatinib (Gleevec) (add reference). BCR::ABL1 is generally favorable in CML (add reference). |

| EXAMPLE: CIC | EXAMPLE: CIC::DUX4 | EXAMPLE: Typically, the last exon of CIC is fused to DUX4. The fusion breakpoint in CIC is usually intra-exonic and removes an inhibitory sequence, upregulating PEA3 genes downstream of CIC including ETV1, ETV4, and ETV5. | EXAMPLE: t(4;19)(q25;q13) | EXAMPLE: Common (CIC-rearranged sarcoma) | EXAMPLE: D | EXAMPLE:

DUX4 has many homologous genes; an alternate translocation in a minority of cases is t(10;19), but this is usually indistinguishable from t(4;19) by short-read sequencing (add references). | |

| EXAMPLE: ALK | EXAMPLE: ELM4::ALK

|

EXAMPLE: Fusions result in constitutive activation of the ALK tyrosine kinase. The most common ALK fusion is EML4::ALK, with breakpoints in intron 19 of ALK. At the transcript level, a variable (5’) partner gene is fused to 3’ ALK at exon 20. Rarely, ALK fusions contain exon 19 due to breakpoints in intron 18. | EXAMPLE: N/A | EXAMPLE: Rare (Lung adenocarcinoma) | EXAMPLE: T | EXAMPLE:

Both balanced and unbalanced forms are observed by FISH (add references). | |

| EXAMPLE: ABL1 | EXAMPLE: N/A | EXAMPLE: Intragenic deletion of exons 2–7 in EGFR removes the ligand-binding domain, resulting in a constitutively active tyrosine kinase with downstream activation of multiple oncogenic pathways. | EXAMPLE: N/A | EXAMPLE: Recurrent (IDH-wildtype Glioblastoma) | EXAMPLE: D, P, T | ||

editv4:Chromosomal Rearrangements (Gene Fusions)The content below was from the old template. Please incorporate above.

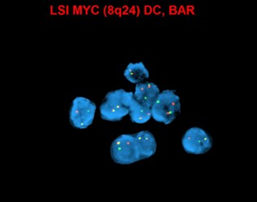

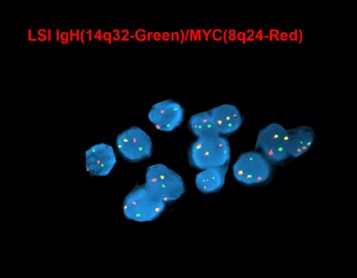

MYC (8q24) up-regulation occurs via translocations, frequently between MYC and immunoglobulin (IG) heavy chain [t(8;14)] and immunoglobulin light chain genes [t(2;8) or t(8;22)], which are also seen in Burkitt lymphoma. These translocations are more common in EBV-positive tumors (74%), and have been associated with poorer prognosis[1][2].

End of V4 Section

editv4:Clinical Significance (Diagnosis, Prognosis and Therapeutic Implications).Please incorporate this section into the relevant tables found in:

- Chromosomal Rearrangements (Gene Fusions)

- Individual Region Genomic Gain/Loss/LOH

- Characteristic Chromosomal Patterns

- Gene Mutations (SNV/INDEL)

- The prognosis of PBL is very poor, with three quarters of patients dying with a median survival of 6-11 months[3][4].

- There is currently no standard therapy for PBL. CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) have been generally considered inadequate, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) favors Hyper-CVAD-MA (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, and high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine), CODOX-M/IVAC (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, and high-dose cytarabine), COMB (cyclophosphamide, Oncovin, methyl-CCNU, and bleomycin), and infusional EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin)[2][5][6].

- Patients with localized disease have a better prognosis, and these individuals can be managed by radiotherapy and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy with radiation therapy[7][8].

- Polychemotherapy is required for patients with disseminated disease; more than 50% achieve complete remissions (CRs), but approximately 70% die of progressive disease, with an event-free survival of 22 months, and an overall survival of 32 months[9].

End of V4 Section

Individual Region Genomic Gain/Loss/LOH

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: Includes aberrations not involving gene rearrangements. Details on clinical significance such as prognosis and other important information can be provided in the notes section. Can refer to CGC workgroup tables as linked on the homepage if applicable. Please include references throughout the table. Do not delete the table.)

| Chr # | Gain, Loss, Amp, LOH | Minimal Region Cytoband and/or Genomic Coordinates [Genome Build; Size] | Relevant Gene(s) | Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Significance - D, P, T | Established Clinical Significance Per Guidelines - Yes or No (Source) | Clinical Relevance Details/Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE:

7 |

EXAMPLE: Loss | EXAMPLE:

chr7 |

EXAMPLE:

Unknown |

EXAMPLE: D, P | EXAMPLE: No | EXAMPLE:

Presence of monosomy 7 (or 7q deletion) is sufficient for a diagnosis of AML with MDS-related changes when there is ≥20% blasts and no prior therapy (add reference). Monosomy 7/7q deletion is associated with a poor prognosis in AML (add references). |

| EXAMPLE:

8 |

EXAMPLE: Gain | EXAMPLE:

chr8 |

EXAMPLE:

Unknown |

EXAMPLE: D, P | EXAMPLE:

Common recurrent secondary finding for t(8;21) (add references). | |

| EXAMPLE:

17 |

EXAMPLE: Amp | EXAMPLE:

17q12; chr17:39,700,064-39,728,658 [hg38; 28.6 kb] |

EXAMPLE:

ERBB2 |

EXAMPLE: D, P, T | EXAMPLE:

Amplification of ERBB2 is associated with HER2 overexpression in HER2 positive breast cancer (add references). Add criteria for how amplification is defined. | |

editv4:Genomic Gain/Loss/LOHThe content below was from the old template. Please incorporate above.

One study of 12 PBL cases showed recurrent gains of 1q31.1q44, 5p15.33p13.1, 7q11.2q11.23, 8q24.13q24.3, 11p and 11q terminal regions, 15q15q26.3, 19p13.3p13.12 and chromosomes 3, 7, 11, and 15, as well as losses of 1p36.33p35.1, 6q25.1q27, 8p23.3p22.14 and 18q21.32q23. Additionally, 54% of the cases had either deletion or copy neutral loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH) involving the tumor suppressor gene CDKN2C at 1p32.3. Furthermore, recurrent copy number losses involving the immunoglobulin genes IGH and IGKV were documented[10].

End of V4 Section

Characteristic Chromosomal or Other Global Mutational Patterns

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: Included in this category are alterations such as hyperdiploid; gain of odd number chromosomes including typically chromosome 1, 3, 5, 7, 11, and 17; co-deletion of 1p and 19q; complex karyotypes without characteristic genetic findings; chromothripsis; microsatellite instability; homologous recombination deficiency; mutational signature pattern; etc. Details on clinical significance such as prognosis and other important information can be provided in the notes section. Please include references throughout the table. Do not delete the table.)

| Chromosomal Pattern | Molecular Pathogenesis | Prevalence -

Common >20%, Recurrent 5-20% or Rare <5% (Disease) |

Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Significance - D, P, T | Established Clinical Significance Per Guidelines - Yes or No (Source) | Clinical Relevance Details/Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE:

Co-deletion of 1p and 18q |

EXAMPLE: See chromosomal rearrangements table as this pattern is due to an unbalanced derivative translocation associated with oligodendroglioma (add reference). | EXAMPLE: Common (Oligodendroglioma) | EXAMPLE: D, P | ||

| EXAMPLE:

Microsatellite instability - hypermutated |

EXAMPLE: Common (Endometrial carcinoma) | EXAMPLE: P, T | |||

editv4:Characteristic Chromosomal Aberrations / PatternsThe content below was from the old template. Please incorporate above.

In addition to the MYC/IG rearrangements, complex karyotypes are also frequently observed. PBL often demonstrates chromosomal changes seen in plasma cell myeloma, including gain of 1q, loss of 1p, deletions 13q and/or 17p, and gains of odd-numbered chromosomes, such as +3, +5, +7, +9, +11, and/or +15[11][12].

End of V4 Section

Gene Mutations (SNV/INDEL)

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: This table is not meant to be an exhaustive list; please include only genes/alterations that are recurrent or common as well either disease defining and/or clinically significant. If a gene has multiple mechanisms depending on the type or site of the alteration, add multiple entries in the table. For clinical significance, denote associations with FDA-approved therapy (not an extensive list of applicable drugs) and NCCN or other national guidelines if applicable; Can also refer to CGC workgroup tables as linked on the homepage if applicable as well as any high impact papers or reviews of gene mutations in this entity. Details on clinical significance such as prognosis and other important information such as concomitant and mutually exclusive mutations can be provided in the notes section. Please include references throughout the table. Do not delete the table.)

| Gene | Genetic Alteration | Tumor Suppressor Gene, Oncogene, Other | Prevalence -

Common >20%, Recurrent 5-20% or Rare <5% (Disease) |

Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Significance - D, P, T | Established Clinical Significance Per Guidelines - Yes or No (Source) | Clinical Relevance Details/Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE:EGFR

|

EXAMPLE: Exon 18-21 activating mutations | EXAMPLE: Oncogene | EXAMPLE: Common (lung cancer) | EXAMPLE: T | EXAMPLE: Yes (NCCN) | EXAMPLE: Exons 18, 19, and 21 mutations are targetable for therapy. Exon 20 T790M variants cause resistance to first generation TKI therapy and are targetable by second and third generation TKIs (add references). |

| EXAMPLE: TP53; Variable LOF mutations

|

EXAMPLE: Variable LOF mutations | EXAMPLE: Tumor Supressor Gene | EXAMPLE: Common (breast cancer) | EXAMPLE: P | EXAMPLE: >90% are somatic; rare germline alterations associated with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (add reference). Denotes a poor prognosis in breast cancer. | |

| EXAMPLE: BRAF; Activating mutations | EXAMPLE: Activating mutations | EXAMPLE: Oncogene | EXAMPLE: Common (melanoma) | EXAMPLE: T | ||

Note: A more extensive list of mutations can be found in cBioportal, COSMIC, and/or other databases. When applicable, gene-specific pages within the CCGA site directly link to pertinent external content.

editv4:Gene Mutations (SNV/INDEL)The content below was from the old template. Please incorporate above.

- IGHV may be unmutated or demonstrate somatic hypermutation[13].

- Montes-Moreno et al. demonstrated somatic mutations in PRDM1(BLIMP1) in 50% of cases[14].

- The largest series of transplant-associated PBL analyzed by next-generation sequencing detected genetic aberrations of the RAS/MAPK, TP53, and NOTCH signaling pathways[15].

End of V4 Section

Epigenomic Alterations

Hypermethylation of p16 has been reported in a case of PBL[4].

Genes and Main Pathways Involved

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: Please include references throughout the table. Do not delete the table.)

| Gene; Genetic Alteration | Pathway | Pathophysiologic Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE: BRAF and MAP2K1; Activating mutations | EXAMPLE: MAPK signaling | EXAMPLE: Increased cell growth and proliferation |

| EXAMPLE: CDKN2A; Inactivating mutations | EXAMPLE: Cell cycle regulation | EXAMPLE: Unregulated cell division |

| EXAMPLE: KMT2C and ARID1A; Inactivating mutations | EXAMPLE: Histone modification, chromatin remodeling | EXAMPLE: Abnormal gene expression program |

editv4:Genes and Main Pathways InvolvedThe content below was from the old template. Please incorporate above.

- MYC expression is suppressed by PRDM1 (BLIMP1) in terminally differentiated B cells; BLIMP1 encodes a transcriptional factor responsible for plasma cell differentiation[2].

- The MYC activation present in PBL (by gene amplification or translocation) results in cellular proliferation and survival upon overcoming PRDM1 (BLIMP1) repression.

End of V4 Section

Genetic Diagnostic Testing Methods

- Diagnosis is usually dependent on morphologic examination and immunohistochemistry demonstrating expression for plasmacytic antigens.

- Conventional cytogenetics has utility in detecting MYC rearrangement and amplification. Most common translocation involves MYC -IGH.

- Next-generation sequencing is helpful for identifying single nucleotide variants of PRDM1 and of genes in the of the RAS/MAPK, TP53, and NOTCH signaling pathways.

Familial Forms

Not applicable.

Additional Information

Put your text here

Links

HAEM4:Lymphomas Associated with HIV Infection

MYC in COSMIC (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cell_lines/gene/analysis?ln=MYC)

References

(use the "Cite" icon at the top of the page) (Instructions: Add each reference into the text above by clicking where you want to insert the reference, selecting the “Cite” icon at the top of the wiki page, and using the “Automatic” tab option to search by PMID to select the reference to insert. If a PMID is not available, such as for a book, please use the “Cite” icon, select “Manual” and then “Basic Form”, and include the entire reference. To insert the same reference again later in the page, select the “Cite” icon and “Re-use” to find the reference; DO NOT insert the same reference twice using the “Automatic” tab as it will be treated as two separate references. The reference list in this section will be automatically generated and sorted.)

- ↑ Bogusz, Agata M.; et al. (2009). "Plasmablastic lymphomas with MYC/IgH rearrangement: report of three cases and review of the literature". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 132 (4): 597–605. doi:10.1309/AJCPFUR1BK0UODTS. ISSN 1943-7722. PMID 19762538.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 Valera, Alexandra; et al. (2010). "IG/MYC rearrangements are the main cytogenetic alteration in plasmablastic lymphomas". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 34 (11): 1686–1694. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f3e29f. ISSN 1532-0979. PMC 2982261. PMID 20962620.

- ↑ Castillo, Jorge J.; et al. (2015). "The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma". Blood. 125 (15): 2323–2330. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-10-567479. ISSN 1528-0020. PMID 25636338.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Morscio, Julie; et al. (2014). "Clinicopathologic comparison of plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV-positive, immunocompetent, and posttransplant patients: single-center series of 25 cases and meta-analysis of 277 reported cases". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 38 (7): 875–886. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000234. ISSN 1532-0979. PMID 24832164.

- ↑ Zelenetz, Andrew D.; et al. (2011). "Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas". Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN. 9 (5): 484–560. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2011.0046. ISSN 1540-1413. PMID 21550968.

- ↑ Koizumi, Yusuke; et al. (2016). "Clinical and pathological aspects of human immunodeficiency virus-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: analysis of 24 cases". International Journal of Hematology. 104 (6): 669–681. doi:10.1007/s12185-016-2082-3. ISSN 1865-3774. PMID 27604616.

- ↑ Phipps, C.; et al. (2017). "Durable remission is achievable with localized treatment and reduction of immunosuppression in limited stage EBV-related plasmablastic lymphoma". Annals of Hematology. 96 (11): 1959–1960. doi:10.1007/s00277-017-3109-4. ISSN 1432-0584. PMID 28831541.

- ↑ Pinnix, Chelsea C.; et al. (2016). "Doxorubicin-Based Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy Produces Favorable Outcomes in Limited-Stage Plasmablastic Lymphoma: A Single-Institution Review". Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia. 16 (3): 122–128. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2015.12.008. ISSN 2152-2669. PMID 26795083.

- ↑ Tchernonog, E.; et al. (2017). "Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of plasmablastic lymphoma patients: analysis of 135 patients from the LYSA group". Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 28 (4): 843–848. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdw684. ISSN 1569-8041. PMID 28031174.

- ↑ Ji, Jianling; et al. (2016-06). "Genomic Profiling of Plasmablastic Lymphoma Reveals Recurrent Copy Number Alterations and MYC Rearrangement as Common Genetic Abnormalities". Cancer Genetics. 209 (6): 290. doi:10.1016/j.cancergen.2016.04.021. ISSN 2210-7762. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Taddesse-Heath, Lekidelu; et al. (2010). "Plasmablastic lymphoma with MYC translocation: evidence for a common pathway in the generation of plasmablastic features". Modern Pathology: An Official Journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 23 (7): 991–999. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2010.72. ISSN 1530-0285. PMC 6344124. PMID 20348882.

- ↑ Meloni-Ehrig, Aurelia; et al. (2017). “Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL)”. Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol. 21 (2): 67-70.

- ↑ Gaidano, Gianluca; et al. (2002). "Molecular histogenesis of plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity". British Journal of Haematology. 119 (3): 622–628. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03872.x. ISSN 0007-1048. PMID 12437635.

- ↑ Montes-Moreno, Santiago; et al. (2017). "Plasmablastic lymphoma phenotype is determined by genetic alterations in MYC and PRDM1". Modern Pathology: An Official Journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 30 (1): 85–94. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2016.162. ISSN 1530-0285. PMID 27687004.

- ↑ Bhagat, Govind; et al. (2017). "Molecular Characterization of Post-Transplant Plasmablastic Lymphomas Implicates RAS, TP53, and NOTCH Mutations and MYC Deregulation in Disease Pathogenesis". Blood. 130 (Supplement 1): 4014–4014. doi:10.1182/blood.V130.Suppl_1.4014.4014. ISSN 0006-4971.

Notes

*Primary authors will typically be those that initially create and complete the content of a page. If a subsequent user modifies the content and feels the effort put forth is of high enough significance to warrant listing in the authorship section, please contact the Associate Editor or other CCGA representative. When pages have a major update, the new author will be acknowledged at the beginning of the page, and those who contributed previously will be acknowledged below as a prior author.

Prior Author(s):

*Citation of this Page: “Plasmablastic lymphoma”. Compendium of Cancer Genome Aberrations (CCGA), Cancer Genomics Consortium (CGC), updated 03/24/2025, https://ccga.io/index.php/HAEM5:Plasmablastic_lymphoma.