Plasmablastic Lymphoma

editPREVIOUS EDITIONThis page from the 4th edition of Haematolymphoid Tumours is being updated. See 5th edition Table of Contents.

Primary Author(s)*

Mark Evans, MD (University of California, Irvine)

Fabiola Quintero-Rivera, MD (University of California, Irvine)

Cancer Category/Type

Mature B-cell neoplasm

Cancer Sub-Classification / Subtype

Plasma cell neoplasm

Definition / Description of Disease

In 1997, Delecluse et al. described a series of large B-cell lymphomas occurring within the jaw and oral cavities of HIV-positive individuals[1]. The cells were blastic in appearance and did not express CD20, but did demonstrate plasmacytic antigens. Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an aggressive proliferation of large B cells with immunoblastic or plasmablastic morphology and plasmacytic phenotype[2]. This entity is distinguished from other large B-cell lymphomas with similar immunoprofiles, such as ALK-positive large B-cell lymphoma and HHV-8-associated lymphoproliferative disorders.

Synonyms / Terminology

Monomorphic plasmablastic lymphoma; plasmablastic lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation

Epidemiology / Prevalence

- Plasmablastic lymphoma typically occurs in adults with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (approximately 73% of cases)[3].

- It is also seen in the setting of iatrogenic immunosuppression (autoimmune disease or post-transplant)[4].

- PBL has been observed in older immunocompetent adults and in children, typically with HIV or immunodeficiency[5][6].

Clinical Features

An extranodal mass is the most typical presentation, and nodal disease is more common in post-transplant PBL[3]. Paraproteins may be detected in some cases[7]. Greater than 50% of cases associated with some form of immunodeficiency present with stage III/IV disease with bone marrow involvement[3][5].

Sites of Involvement

Typically head and neck regions, particularly the oral cavity. Other less commonly involved sites include the gastrointestinal tract, skin, soft tissue, lung, bone, and rarely lymph nodes[8].

Morphologic Features

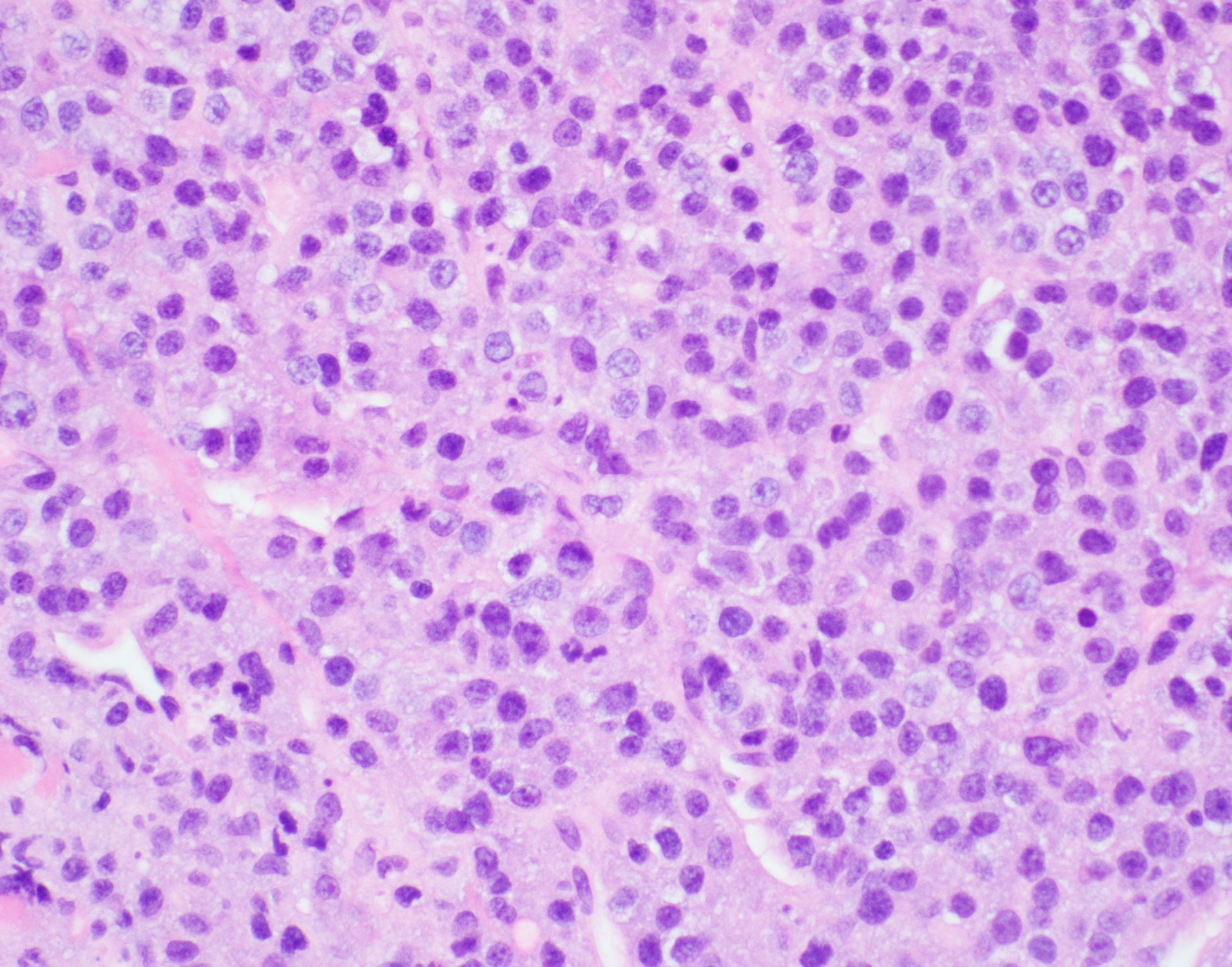

Two histologic variants have been described:

- The monomorphic variant features large immunoblast-like cells with fine nuclear chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and little or no plasmacytic differentiation; a starry sky pattern is common.

- The variant with plasmacytic differentiation is composed of cells with course nuclear chromatin, basophilic cytoplasm, eccentric nuclei, and paranuclear hof.

- Some cases demonstrate features of both variants[2].

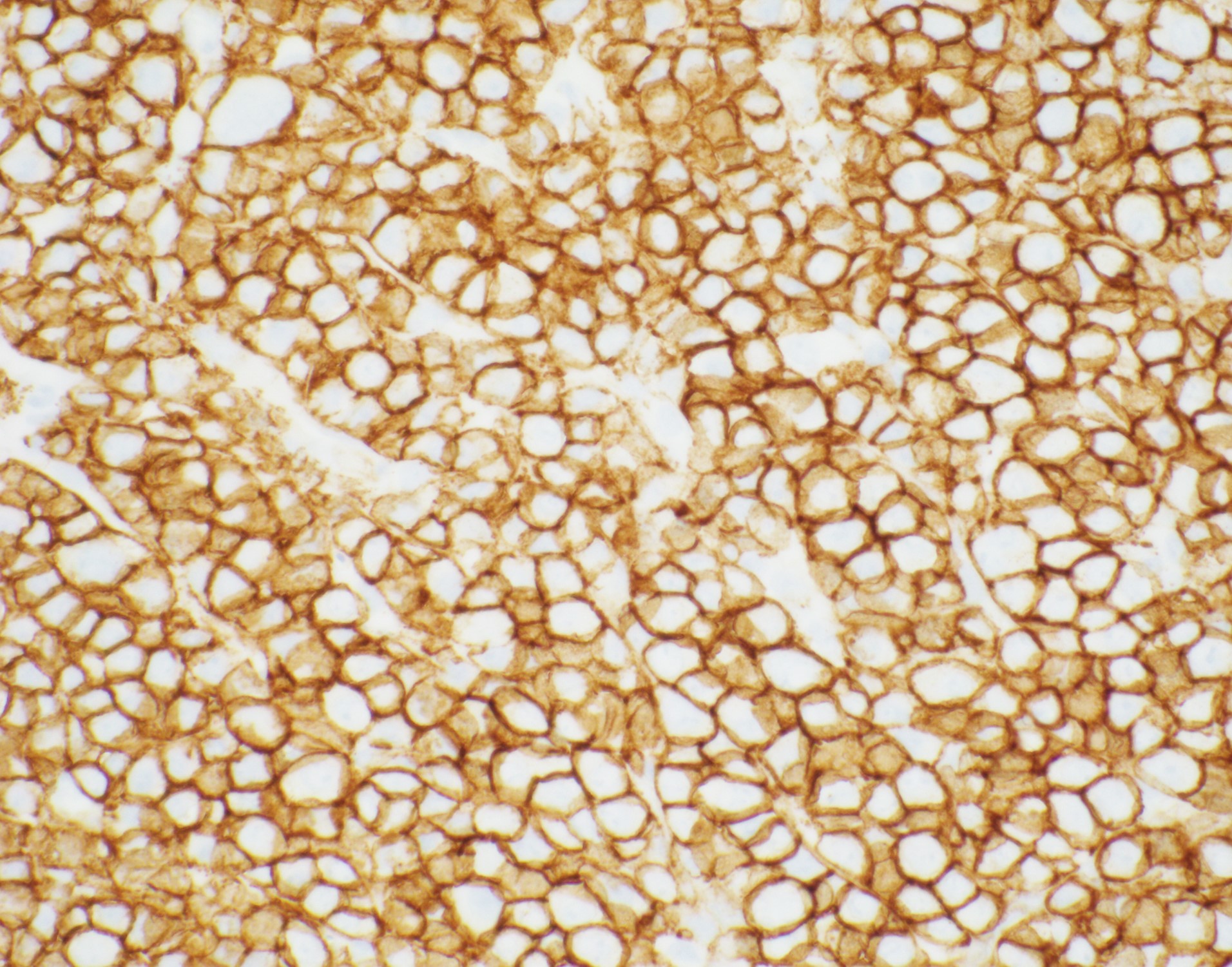

Immunophenotype

The cells express plasmacytic antigens (CD138, VS38c, IRF4/MUM1, BLIMP1, XBP1, and CD38). CD45, PAX-5, and CD20 are typically negative or weakly positive. Cytoplasmic IgG, as well as kappa and lambda light chains are common. CD79a is present in approximately 40% of cases, and CD56 in about 25%. The cells are typically positive for Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA (EBER). Ki-67 proliferation index is usually >90%[8][9].

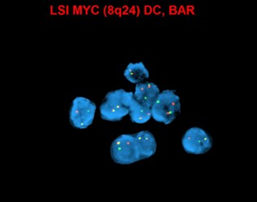

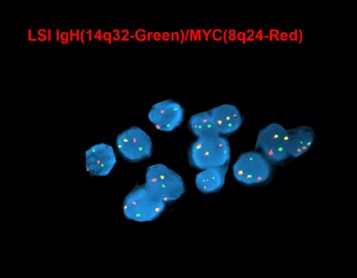

Chromosomal Rearrangements (Gene Fusions)

MYC (8q24) up-regulation occurs via translocations, frequently between MYC and immunoglobulin (IG) heavy chain [t(8;14)] and immunoglobulin light chain genes [t(2;8) or t(8;22)], which are also seen in Burkitt lymphoma. These translocations are more common in EBV-positive tumors (74%), and have been associated with poorer prognosis[10][11].

Characteristic Chromosomal Aberrations / Patterns

In addition to the MYC/IG rearrangements, complex karyotypes are also frequently observed. PBL often demonstrates chromosomal changes seen in plasma cell myeloma, including gain of 1q, loss of 1p, deletions 13q and/or 17p, and gains of odd-numbered chromosomes, such as +3, +5, +7, +9, +11, and/or +15[7][12].

Genomic Gain/Loss/LOH

One study of 12 PBL cases showed recurrent gains of 1q31.1q44, 5p15.33p13.1, 7q11.2q11.23, 8q24.13q24.3, 11p and 11q terminal regions, 15q15q26.3, 19p13.3p13.12 and chromosomes 3, 7, 11, and 15, as well as losses of 1p36.33p35.1, 6q25.1q27, 8p23.3p22.14 and 18q21.32q23. Additionally, 54% of the cases had either deletion or copy neutral loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH) involving the tumor suppressor gene CDKN2C at 1p32.3. Furthermore, recurrent copy number losses involving the immunoglobulin genes IGH and IGKV were documented[13].

Gene Mutations (SNV/INDEL)

- IGHV may be unmutated or demonstrate somatic hypermutation[14].

- Montes-Moreno et al. demonstrated somatic mutations in PRDM1(BLIMP1) in 50% of cases[15].

- The largest series of transplant-associated PBL analyzed by next-generation sequencing detected genetic aberrations of the RAS/MAPK, TP53, and NOTCH signaling pathways[16].

Epigenomics (Methylation)

Hypermethylation of p16 has been reported in a case of PBL[17].

Genes and Main Pathways Involved

- MYC expression is suppressed by PRDM1 (BLIMP1) in terminally differentiated B cells; BLIMP1 encodes a transcriptional factor responsible for plasma cell differentiation[11].

- The MYC activation present in PBL (by gene amplification or translocation) results in cellular proliferation and survival upon overcoming PRDM1 (BLIMP1) repression.

Diagnostic Testing Methods

- Diagnosis is usually dependent on morphologic examination and immunohistochemistry demonstrating expression for plasmacytic antigens.

- Conventional cytogenetics has utility in detecting MYC rearrangement and amplification. Most common translocation involves MYC -IGH.

- Next-generation sequencing is helpful for identifying single nucleotide variants of PRDM1 and of genes in the of the RAS/MAPK, TP53, and NOTCH signaling pathways.

Clinical Significance (Diagnosis, Prognosis and Therapeutic Implications)

- The prognosis of PBL is very poor, with three quarters of patients dying with a median survival of 6-11 months[3][17].

- There is currently no standard therapy for PBL. CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) have been generally considered inadequate, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) favors Hyper-CVAD-MA (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, and high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine), CODOX-M/IVAC (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, and high-dose cytarabine), COMB (cyclophosphamide, Oncovin, methyl-CCNU, and bleomycin), and infusional EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin)[11][18][19].

- Patients with localized disease have a better prognosis, and these individuals can be managed by radiotherapy and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy with radiation therapy[20][21].

- Polychemotherapy is required for patients with disseminated disease; more than 50% achieve complete remissions (CRs), but approximately 70% die of progressive disease, with an event-free survival of 22 months, and an overall survival of 32 months[22].

Familial Forms

Not applicable.

Links

HAEM4:Lymphomas Associated with HIV Infection

MYC in COSMIC (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cell_lines/gene/analysis?ln=MYC)

References

- ↑ Delecluse, H. J.; et al. (1997). "Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection". Blood. 89 (4): 1413–1420. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 9028965.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Campo, E.; et al. (2016). Plasmablastic lymphoma. in World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Revised 4th edition. Swerdlow, S.H.; Campo, E.; Harris, N.L.; Jaffe, E.S.; et al. Editors. IARC Press: Lyon, France. p 321-322.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Castillo, Jorge J.; et al. (2015). "The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma". Blood. 125 (15): 2323–2330. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-10-567479. ISSN 1528-0020. PMID 25636338.

- ↑ Borenstein, J.; et al. (2007). "Plasmablastic lymphomas may occur as post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders". Histopathology. 51 (6): 774–777. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02870.x. ISSN 0309-0167. PMID 17944927.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Colomo, Lluís; et al. (2004). "Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with plasmablastic differentiation represent a heterogeneous group of disease entities". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 28 (6): 736–747. doi:10.1097/01.pas.0000126781.87158.e3. ISSN 0147-5185. PMID 15166665.

- ↑ Liu, Fang; et al. (2012). "Plasmablastic lymphoma of the elderly: a clinicopathological comparison with age-related Epstein-Barr virus-associated B cell lymphoproliferative disorder". Histopathology. 61 (6): 1183–1197. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04339.x. ISSN 1365-2559. PMID 22958176.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Taddesse-Heath, Lekidelu; et al. (2010). "Plasmablastic lymphoma with MYC translocation: evidence for a common pathway in the generation of plasmablastic features". Modern Pathology: An Official Journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 23 (7): 991–999. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2010.72. ISSN 1530-0285. PMC 6344124. PMID 20348882.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Campo, E. (2017). Plasmablastic neoplasms other than plasma cell myeloma. in Hematopathology. 2nd edition. Jaffe, E.S.; Arber, D.A.; Campo, E.; et al. Editors. Elsevier: Philadelphia. p 465-472.

- ↑ Montes-Moreno, Santiago; et al. (2010). "Aggressive large B-cell lymphoma with plasma cell differentiation: immunohistochemical characterization of plasmablastic lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with partial plasmablastic phenotype". Haematologica. 95 (8): 1342–1349. doi:10.3324/haematol.2009.016113. ISSN 1592-8721. PMC 2913083. PMID 20418245.

- ↑ Bogusz, Agata M.; et al. (2009). "Plasmablastic lymphomas with MYC/IgH rearrangement: report of three cases and review of the literature". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 132 (4): 597–605. doi:10.1309/AJCPFUR1BK0UODTS. ISSN 1943-7722. PMID 19762538.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Valera, Alexandra; et al. (2010). "IG/MYC rearrangements are the main cytogenetic alteration in plasmablastic lymphomas". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 34 (11): 1686–1694. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f3e29f. ISSN 1532-0979. PMC 2982261. PMID 20962620.

- ↑ Meloni-Ehrig, Aurelia; et al. (2017). “Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL)”. Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol. 21 (2): 67-70.

- ↑ Ji, Jianling; et al. (2016-06). "Genomic Profiling of Plasmablastic Lymphoma Reveals Recurrent Copy Number Alterations and MYC Rearrangement as Common Genetic Abnormalities". Cancer Genetics. 209 (6): 290. doi:10.1016/j.cancergen.2016.04.021. ISSN 2210-7762. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Gaidano, Gianluca; et al. (2002). "Molecular histogenesis of plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity". British Journal of Haematology. 119 (3): 622–628. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03872.x. ISSN 0007-1048. PMID 12437635.

- ↑ Montes-Moreno, Santiago; et al. (2017). "Plasmablastic lymphoma phenotype is determined by genetic alterations in MYC and PRDM1". Modern Pathology: An Official Journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 30 (1): 85–94. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2016.162. ISSN 1530-0285. PMID 27687004.

- ↑ Bhagat, Govind; et al. (2017). "Molecular Characterization of Post-Transplant Plasmablastic Lymphomas Implicates RAS, TP53, and NOTCH Mutations and MYC Deregulation in Disease Pathogenesis". Blood. 130 (Supplement 1): 4014–4014. doi:10.1182/blood.V130.Suppl_1.4014.4014. ISSN 0006-4971.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Morscio, Julie; et al. (2014). "Clinicopathologic comparison of plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV-positive, immunocompetent, and posttransplant patients: single-center series of 25 cases and meta-analysis of 277 reported cases". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 38 (7): 875–886. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000234. ISSN 1532-0979. PMID 24832164.

- ↑ Zelenetz, Andrew D.; et al. (2011). "Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas". Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN. 9 (5): 484–560. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2011.0046. ISSN 1540-1413. PMID 21550968.

- ↑ Koizumi, Yusuke; et al. (2016). "Clinical and pathological aspects of human immunodeficiency virus-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: analysis of 24 cases". International Journal of Hematology. 104 (6): 669–681. doi:10.1007/s12185-016-2082-3. ISSN 1865-3774. PMID 27604616.

- ↑ Phipps, C.; et al. (2017). "Durable remission is achievable with localized treatment and reduction of immunosuppression in limited stage EBV-related plasmablastic lymphoma". Annals of Hematology. 96 (11): 1959–1960. doi:10.1007/s00277-017-3109-4. ISSN 1432-0584. PMID 28831541.

- ↑ Pinnix, Chelsea C.; et al. (2016). "Doxorubicin-Based Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy Produces Favorable Outcomes in Limited-Stage Plasmablastic Lymphoma: A Single-Institution Review". Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia. 16 (3): 122–128. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2015.12.008. ISSN 2152-2669. PMID 26795083.

- ↑ Tchernonog, E.; et al. (2017). "Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of plasmablastic lymphoma patients: analysis of 135 patients from the LYSA group". Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 28 (4): 843–848. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdw684. ISSN 1569-8041. PMID 28031174.

Notes

*Primary authors will typically be those that initially create and complete the content of a page. If a subsequent user modifies the content and feels the effort put forth is of high enough significance to warrant listing in the authorship section, please contact the CCGA coordinators (contact information provided on the homepage). Additional global feedback or concerns are also welcome.