B-lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma with iAMP21

Haematolymphoid Tumours (WHO Classification, 5th ed.)

Primary Author(s)*

Holli M. Drendel, PhD, FACMGG, Carolinas Pathology Group, Charlotte

WHO Classification of Disease

| Structure | Disease |

|---|---|

| Book | Haematolymphoid Tumours (5th ed.) |

| Category | B-cell lymphoid proliferations and lymphomas |

| Family | Precursor B-cell neoplasms |

| Type | B-lymphoblastic leukaemias/lymphomas |

| Subtype(s) | B-lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma with iAMP21 |

Definition / Description of Disease

Intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21 (iAMP21) is a neoplasm of lymphoblasts that are of the B-cell lineage. It is characterized by amplification of the RUNX1 gene at 21q22.3 on a structurally abnormal chromosome 21. Amplification is defined as ≥5 copies of RUNX1 detected by FISH or ≥3 copies of RUNX1 on a single abnormal chromosome 21.[1]

Synonyms / Terminology

Put your text here

Epidemiology / Prevalence

iAMP21 is observed most often in the older pediatric group (median age of 9 years, with a range of 2-30 years). It accounts for ~2% of B-ALL cases including ~2% of standard-risk and 3% of high-risk patients. The incidence in adult B-ALL has not been established; however, it appears to be less prevalent than in the pediatric population.[2]

Further, patients carrying a rob(15;21)(q10;q10) have an ~2700-fold increased risk of developing iAMP21 ALL compared to the general population. Additionally, patients with a constitutional ring chromosome 21, r(21), may potentially be predisposed to iAMP21 ALL.[2]

Clinical Features

~50% of cases are classified as high-risk based on an age of ≥10 years.[3] Pediatric iAMP21 has been associated with a poor outcome. It displays an increased rate of relapse when treated on standard protocols. Further, the event-free survival and overall survival were significantly worse for individuals with the iAMP21 and standard-risk B-ALL, but not significant in individuals with iAMP21 and high-risk B-ALL.

| Signs and Symptoms | N/A |

| Laboratory Findings | Low platelet count

Low WBC count (<50,000/μl) |

Sites of Involvement

Bone Marrow and peripheral blood

Morphologic Features

There are no unique morphological or cytochemical features that distinguish this entity from other types of ALL.[1]

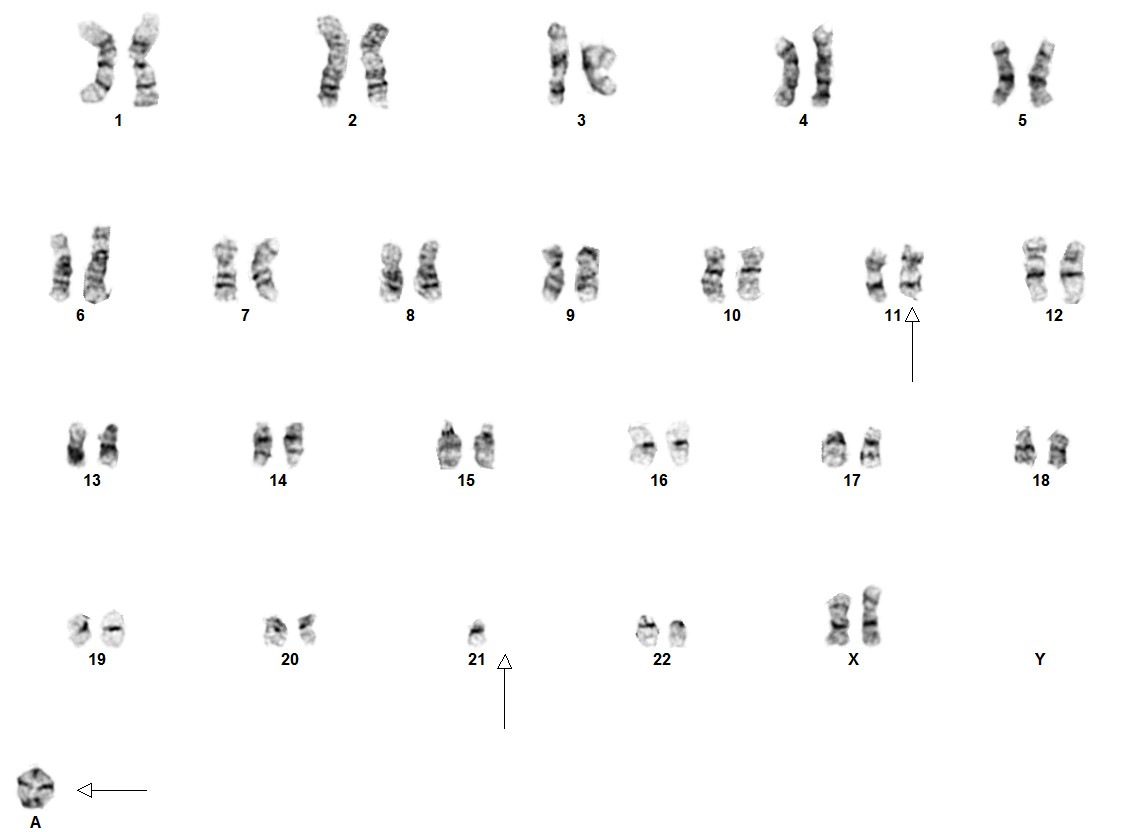

Cytogenetic morphology of the abnormal chromosome 21 can vary markedly between patients.[4]

Immunophenotype

No detailed information is known, other than these cases occur exclusively in B-ALL.[1]

| Finding | Marker |

|---|---|

| Positive (universal) | N/A |

| Positive (subset) | N/A |

| Negative (universal) | N/A |

| Negative (subset) | N/A |

Chromosomal Rearrangements (Gene Fusions)

Some rearrangements have been seen as secondary abnormalities.

| Chromosomal Rearrangement | Genes in Fusion (5’ or 3’ Segments) | Pathogenic Derivative | Prevalence | Diagnostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Prognostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Therapeutic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| del(X)(p22.33p22.33)/del(Y)(p11.32p11.32) | P2RY8-CRLF2 | der(X)/der(Y) | Because of the unique nature of the iAMP21 abnormality, cases that present with additional genomic lesions that may suggest another category, such as a CRLF2 rearrangement, should still be classified as B-ALL with iAMP21. | ||||

| t(12;21)(p13.2;q22.1) | ETV6-RUNX1 | der(21) | |||||

| t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) | BCR-ABL1 | der(22) |

Individual Region Genomic Gain/Loss/LOH

In ~80% of iAMP21 B-ALL cases, recurrent secondary abnormalities, both chromosomal and molecular, have been documented. Deletions involving particular genes such as; IKZF1, CDKN2A/B, PAX5, SH2B3, ETV6 and RB1 have also been observed.

| Chr # | Gain / Loss / Amp / LOH | Minimal Region Genomic Coordinates [Genome Build] | Minimal Region Cytoband | Diagnostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Prognostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Therapeutic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Gain | EXAMPLE:

chr7:1- 159,335,973 [hg38] |

EXAMPLE:

chr7 |

Yes | Yes | No | EXAMPLE:

Presence of monosomy 7 (or 7q deletion) is sufficient for a diagnosis of AML with MDS-related changes when there is ≥20% blasts and no prior therapy (add reference). Monosomy 7/7q deletion is associated with a poor prognosis in AML (add reference). |

| 10 | Gain | EXAMPLE:

chr8:1-145,138,636 [hg38] |

EXAMPLE:

chr8 |

No | No | No | EXAMPLE:

Common recurrent secondary finding for t(8;21) (add reference). |

| 14 | Gain | ||||||

| 7/7q | Loss | ||||||

| 11q | Loss |

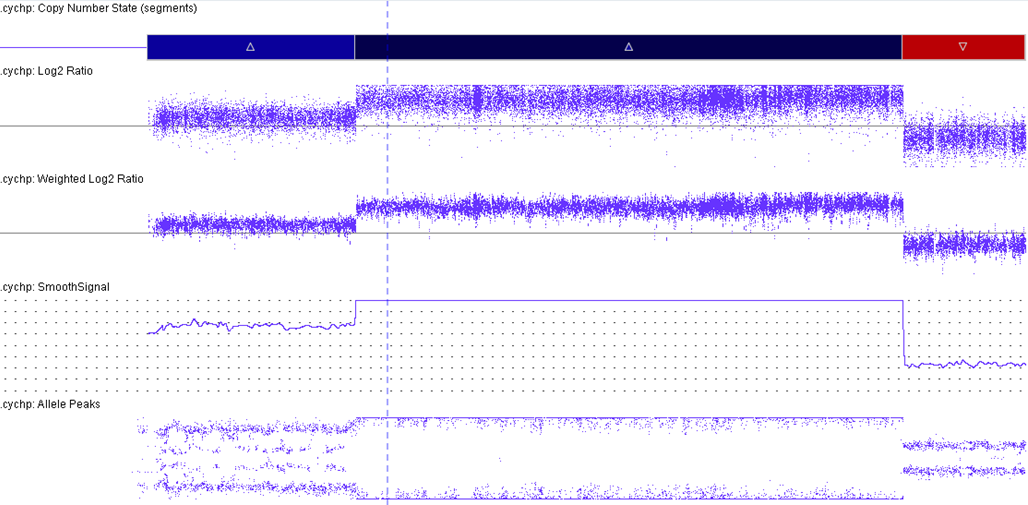

Characteristic Chromosomal Patterns

iAMP21 cases have a characteristic pattern that is both complex and variable. This pattern comprises multiple regions of gain, amplification and deletion. Interestingly, RUNX1 amplification is not always intrachromosomal.[5][6] The formation of iAMP21 is considered to be due to breakage-fusion-bridge cycles followed by chromothripsis and other complex structural rearrangements of chromosome 21. Studies, molecular and cytogenetic, have elucidated a common 5.1 Mb region that includes the RUNX1 gene. However, even though RUNX1 is included in the amplified region, there has not yet been any conclusive evidence that RUNX1 is critical in the pathogenesis of disease given that it is not overexpressed in some individuals with this abnormality.[2][7][8]

| Chromosomal Pattern | Diagnostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Prognostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Therapeutic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification of RUNX1 | See CMA image displaying the amplification of RUNX1. This is part of the critical region consistently amplified: chr21:32.8-37.9 Mb (hg19). | |||

| Terminal deletion of 21q |

Gene Mutations (SNV/INDEL)

In a 2016 paper, it was shown that in the iAMP21-ALL exome, the mutations were more commonly transitions (for example: C>T) than transversions or indels.[2][9] Frequently, mutations in the RAS signaling pathway have been observed. Interestingly, these mutations were observed to coexist in patterns ranging from 2-3 mutated genes to 2-4 mutations in the same gene in one sample. Further, the FLT3-ITD was more prevalent in iAMP21-ALL.[9]

| Gene; Genetic Alteration | Presumed Mechanism (Tumor Suppressor Gene [TSG] / Oncogene / Other) | Prevalence (COSMIC / TCGA / Other) | Concomitant Mutations | Mutually Exclusive Mutations | Diagnostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Prognostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Therapeutic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRAS | EXAMPLE: TSG | 45% | EXAMPLE: IDH1 R123H | EXAMPLE: EGFR amplification | EXAMPLE: Excludes hairy cell leukemia (HCL) (add reference). | |||

| KRAS | 18% | |||||||

| FLT3 | 20% | |||||||

| PTPN11 | 11% | |||||||

| BRAF | 2% | |||||||

| NF1 | 2% |

Note: A more extensive list of mutations can be found in cBioportal (https://www.cbioportal.org/), COSMIC (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), ICGC (https://dcc.icgc.org/) and/or other databases. When applicable, gene-specific pages within the CCGA site directly link to pertinent external content.

Epigenomic Alterations

N/A

Genes and Main Pathways Involved

Put your text here and fill in the table

| Gene; Genetic Alteration | Pathway | Pathophysiologic Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| RUNX1 | RAS pathway[9] | EXAMPLE: Increased cell growth and proliferation |

| EXAMPLE: CDKN2A; Inactivating mutations | EXAMPLE: Cell cycle regulation | EXAMPLE: Unregulated cell division |

| EXAMPLE: KMT2C and ARID1A; Inactivating mutations | EXAMPLE: Histone modification, chromatin remodeling | EXAMPLE: Abnormal gene expression program |

Genetic Diagnostic Testing Methods

Different methodologies are able to detect the iAMP21, such as:

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) utilizing the probe set for the t(12;21)

- Conventional chromosome analysis

- Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA)

- Chromosomal microarray (CMA)

- Next generation sequencing (NGS).

Familial Forms

N/A

Additional Information

N/A

Links

References

(use the "Cite" icon at the top of the page) (Instructions: Add each reference into the text above by clicking on where you want to insert the reference, selecting the “Cite” icon at the top of the page, and using the “Automatic” tab option to search such as by PMID to select the reference to insert. The reference list in this section will be automatically generated and sorted. If a PMID is not available, such as for a book, please use the “Cite” icon, select “Manual” and then “Basic Form”, and include the entire reference.)

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Borowitz MJ, et al., (2017). B-Lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma with recurrent genetic abnormalities, in World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Revised 4th edition. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Arber DA, Hasserjian RP, Le Beau MM, Orazi A, and Siebert R, Editors. IARC Press: Lyon, France.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Akkari, Yassmine M. N.; et al. (2020-05). "Evidence-based review of genomic aberrations in B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma: Report from the cancer genomics consortium working group for lymphoblastic leukemia". Cancer Genetics. 243: 52–72. doi:10.1016/j.cancergen.2020.03.001. ISSN 2210-7762. PMID 32302940 Check

|pmid=value (help). Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ Harrison, Christine J. (2015-02-26). "Blood Spotlight on iAMP21 acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), a high-risk pediatric disease". Blood. 125 (9): 1383–1386. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-08-569228. ISSN 1528-0020. PMID 25608562.

- ↑ Harewood, L.; et al. (2003-03). "Amplification of AML1 on a duplicated chromosome 21 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a study of 20 cases". Leukemia. 17 (3): 547–553. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2402849. ISSN 0887-6924. PMID 12646943. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Arber, Daniel A. (04 2019). "The 2016 WHO classification of acute myeloid leukemia: What the practicing clinician needs to know". Seminars in Hematology. 56 (2): 90–95. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2018.08.002. ISSN 1532-8686. PMID 30926096. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Johnson, Ryan C.; et al. (2015-07). "Cytogenetic Variation of B-Lymphoblastic Leukemia With Intrachromosomal Amplification of Chromosome 21 (iAMP21): A Multi-Institutional Series Review". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 144 (1): 103–112. doi:10.1309/AJCPLUYF11HQBYRB. ISSN 1943-7722. PMID 26071468. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Rand, Vikki; et al. (2011-06-23). "Genomic characterization implicates iAMP21 as a likely primary genetic event in childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Blood. 117 (25): 6848–6855. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-01-329961. ISSN 1528-0020. PMID 21527530.

- ↑ Hunger, Stephen P.; et al. (2012-05-10). "Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: a report from the children's oncology group". Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 30 (14): 1663–1669. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8018. ISSN 1527-7755. PMC 3383113. PMID 22412151.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Ryan, S. L.; et al. (09 2016). "The role of the RAS pathway in iAMP21-ALL". Leukemia. 30 (9): 1824–1831. doi:10.1038/leu.2016.80. ISSN 1476-5551. PMC 5017527. PMID 27168466. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

Notes

*Primary authors will typically be those that initially create and complete the content of a page. If a subsequent user modifies the content and feels the effort put forth is of high enough significance to warrant listing in the authorship section, please contact the CCGA coordinators (contact information provided on the homepage). Additional global feedback or concerns are also welcome. *Citation of this Page: “B-lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma with iAMP21”. Compendium of Cancer Genome Aberrations (CCGA), Cancer Genomics Consortium (CGC), updated 09/6/2024, https://ccga.io/index.php/HAEM5:B-lymphoblastic_leukaemia/lymphoma_with_iAMP21.