Acute myeloid leukaemia with BCR::ABL1 fusion

Haematolymphoid Tumours (WHO Classification, 5th ed.)

| This page is under construction |

editContent Update To WHO 5th Edition Classification Is In Process; Content Below is Based on WHO 4th Edition ClassificationThis page was converted to the new template on 2023-12-07. The original page can be found at HAEM4:Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) with BCR-ABL1.

(General Instructions – The focus of these pages is the clinically significant genetic alterations in each disease type. This is based on up-to-date knowledge from multiple resources such as PubMed and the WHO classification books. The CCGA is meant to be a supplemental resource to the WHO classification books; the CCGA captures in a continually updated wiki-stye manner the current genetics/genomics knowledge of each disease, which evolves more rapidly than books can be revised and published. If the same disease is described in multiple WHO classification books, the genetics-related information for that disease will be consolidated into a single main page that has this template (other pages would only contain a link to this main page). Use HUGO-approved gene names and symbols (italicized when appropriate), HGVS-based nomenclature for variants, as well as generic names of drugs and testing platforms or assays if applicable. Please complete tables whenever possible and do not delete them (add N/A if not applicable in the table and delete the examples); to add (or move) a row or column in a table, click nearby within the table and select the > symbol that appears. Please do not delete or alter the section headings. The use of bullet points alongside short blocks of text rather than only large paragraphs is encouraged. Additional instructions below in italicized blue text should not be included in the final page content. Please also see Author_Instructions and FAQs as well as contact your Associate Editor or Technical Support.)

Primary Author(s)*

Kay Weng Choy MBBS, Monash Medical Centre

WHO Classification of Disease

| Structure | Disease |

|---|---|

| Book | Haematolymphoid Tumours (5th ed.) |

| Category | Myeloid proliferations and neoplasms |

| Family | Acute myeloid leukaemia |

| Type | Acute myeloid leukaemia with defining genetic abnormalities |

| Subtype(s) | Acute myeloid leukaemia with BCR::ABL1 fusion |

WHO Essential and Desirable Genetic Diagnostic Criteria

(Instructions: The table will have the diagnostic criteria from the WHO book autocompleted; remove any non-genetics related criteria. If applicable, add text about other classification systems that define this entity and specify how the genetics-related criteria differ.)

| WHO Essential Criteria (Genetics)* | |

| WHO Desirable Criteria (Genetics)* | |

| Other Classification |

*Note: These are only the genetic/genomic criteria. Additional diagnostic criteria can be found in the WHO Classification of Tumours.

Related Terminology

(Instructions: The table will have the related terminology from the WHO autocompleted.)

| Acceptable | |

| Not Recommended |

Gene Rearrangements

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: Details on clinical significance such as prognosis and other important information can be provided in the notes section. Please include references throughout the table. Do not delete the table.)

| Driver Gene | Fusion(s) and Common Partner Genes | Molecular Pathogenesis | Typical Chromosomal Alteration(s) | Prevalence -Common >20%, Recurrent 5-20% or Rare <5% (Disease) | Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Significance - D, P, T | Established Clinical Significance Per Guidelines - Yes or No (Source) | Clinical Relevance Details/Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE: ABL1 | EXAMPLE: BCR::ABL1 | EXAMPLE: The pathogenic derivative is the der(22) resulting in fusion of 5’ BCR and 3’ABL1. | EXAMPLE: t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) | EXAMPLE: Common (CML) | EXAMPLE: D, P, T | EXAMPLE: Yes (WHO, NCCN) | EXAMPLE:

The t(9;22) is diagnostic of CML in the appropriate morphology and clinical context (add reference). This fusion is responsive to targeted therapy such as Imatinib (Gleevec) (add reference). BCR::ABL1 is generally favorable in CML (add reference). |

| EXAMPLE: CIC | EXAMPLE: CIC::DUX4 | EXAMPLE: Typically, the last exon of CIC is fused to DUX4. The fusion breakpoint in CIC is usually intra-exonic and removes an inhibitory sequence, upregulating PEA3 genes downstream of CIC including ETV1, ETV4, and ETV5. | EXAMPLE: t(4;19)(q25;q13) | EXAMPLE: Common (CIC-rearranged sarcoma) | EXAMPLE: D | EXAMPLE:

DUX4 has many homologous genes; an alternate translocation in a minority of cases is t(10;19), but this is usually indistinguishable from t(4;19) by short-read sequencing (add references). | |

| EXAMPLE: ALK | EXAMPLE: ELM4::ALK

|

EXAMPLE: Fusions result in constitutive activation of the ALK tyrosine kinase. The most common ALK fusion is EML4::ALK, with breakpoints in intron 19 of ALK. At the transcript level, a variable (5’) partner gene is fused to 3’ ALK at exon 20. Rarely, ALK fusions contain exon 19 due to breakpoints in intron 18. | EXAMPLE: N/A | EXAMPLE: Rare (Lung adenocarcinoma) | EXAMPLE: T | EXAMPLE:

Both balanced and unbalanced forms are observed by FISH (add references). | |

| EXAMPLE: ABL1 | EXAMPLE: N/A | EXAMPLE: Intragenic deletion of exons 2–7 in EGFR removes the ligand-binding domain, resulting in a constitutively active tyrosine kinase with downstream activation of multiple oncogenic pathways. | EXAMPLE: N/A | EXAMPLE: Recurrent (IDH-wildtype Glioblastoma) | EXAMPLE: D, P, T | ||

editv4:Chromosomal Rearrangements (Gene Fusions)The content below was from the old template. Please incorporate above.

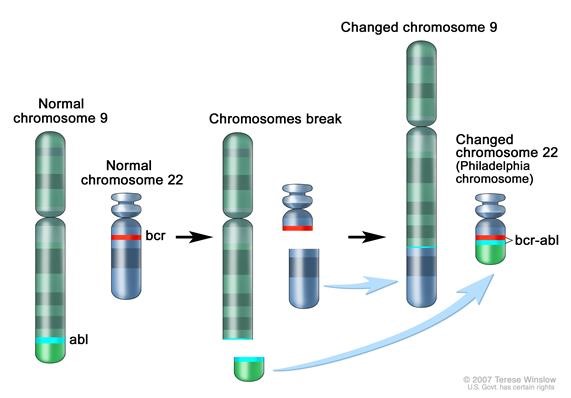

The t(9:22)(q34.1;q11.2) results in the formation of the Ph chromosome and the chimeric BCR-ABL1 fusion gene. In AML, the most common BCR-ABL1 transcripts p190 and p210 have been detected in nearly equal distribution[1]. Since p190 is very rare in CML (p210 transcripts in >99% of cases), the presentation with a p190 transcript is in favour of the diagnosis of AML rather than CML[2].

| Chromosomal Rearrangement | Genes in Fusion (5’ or 3’ Segments) | Pathogenic Derivative | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) | 3'ABL1 / 5'BCR | der(22) | <3% of AML |

End of V4 Section

editv4:Clinical Significance (Diagnosis, Prognosis and Therapeutic Implications).Please incorporate this section into the relevant tables found in:

- Chromosomal Rearrangements (Gene Fusions)

- Individual Region Genomic Gain/Loss/LOH

- Characteristic Chromosomal Patterns

- Gene Mutations (SNV/INDEL)

BCR-ABL1 positive AML is an emerging entity. The proliferation of BCR-ABL1 positive blasts present a diagnostic dilemma. While it may be difficult, it is essential to distinguish between BCR-ABL1 positive AML and CML-MBC, in order to choose the most appropriate therapy (e.g., intensive induction chemotherapy versus tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) followed by an early allogeneic stem cell transplant). After the exclusion of acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage (a separate entity according to WHO) by flow cytometry, it is helpful to note any past history of antecedent hematological disease. Absence of basophilia and absence of splenomegaly favour the diagnosis of BCR-ABL1 positive AML (over CML-MBC). The detection of p190 transcript and the occurrence of any BCR-ABL1 transcript in less than 100% of metaphases supports the diagnosis of AML rather than CML. Persistent CCyR (Complete Cytogenetic Response) after conventional chemotherapy is unusual for CML-MBC and supports the diagnosis of BCR-ABL1 positive AML[1].

The overall prognosis of BCR-ABL1 positive AML is generally unfavourable. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for AML categorise this entity into the poor-risk group, comparable with complex aberrant karyotype AML[3]. It appears that the prognosis of BCR-ABL1 positive AML depends more on the genetic background (concurrent aberrations) than on BCR-ABL1 itself. Unlike in CML, BCR-ABL1 does not appear to be the key driver in AML though may provide a proliferative advantage to a particular BCR-ABL1 positive subclone There is currently no standardized treatment approach for BCR-ABL1 positive AML. Therapy with TKI alone does not produce sustained responses in BCR-ABL1 positive AML. This may be due to a very rapid clonal evolution, resulting in resistance in a much higher proportion of patients and in a significantly shorter time than in CML[1].

End of V4 Section

Individual Region Genomic Gain/Loss/LOH

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: Includes aberrations not involving gene rearrangements. Details on clinical significance such as prognosis and other important information can be provided in the notes section. Can refer to CGC workgroup tables as linked on the homepage if applicable. Please include references throughout the table. Do not delete the table.)

| Chr # | Gain, Loss, Amp, LOH | Minimal Region Cytoband and/or Genomic Coordinates [Genome Build; Size] | Relevant Gene(s) | Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Significance - D, P, T | Established Clinical Significance Per Guidelines - Yes or No (Source) | Clinical Relevance Details/Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE:

7 |

EXAMPLE: Loss | EXAMPLE:

chr7 |

EXAMPLE:

Unknown |

EXAMPLE: D, P | EXAMPLE: No | EXAMPLE:

Presence of monosomy 7 (or 7q deletion) is sufficient for a diagnosis of AML with MDS-related changes when there is ≥20% blasts and no prior therapy (add reference). Monosomy 7/7q deletion is associated with a poor prognosis in AML (add references). |

| EXAMPLE:

8 |

EXAMPLE: Gain | EXAMPLE:

chr8 |

EXAMPLE:

Unknown |

EXAMPLE: D, P | EXAMPLE:

Common recurrent secondary finding for t(8;21) (add references). | |

| EXAMPLE:

17 |

EXAMPLE: Amp | EXAMPLE:

17q12; chr17:39,700,064-39,728,658 [hg38; 28.6 kb] |

EXAMPLE:

ERBB2 |

EXAMPLE: D, P, T | EXAMPLE:

Amplification of ERBB2 is associated with HER2 overexpression in HER2 positive breast cancer (add references). Add criteria for how amplification is defined. | |

editv4:Genomic Gain/Loss/LOHThe content below was from the old template. Please incorporate above.

AML with BCR-ABL1 carries unique genome imbalances. Nacheva et al., used array comparative genomic hybridisation (CGH) to perform a comparative study between several BCR-ABL1 positive entities. BCR-ABL1 positive AML displays characteristic of lymphoid disease (found in BCR-ABL1 positive ALL and CML): deletions of IKZF1 and/or CDKN2A/B genes were recurrent findings in BCR-ABL1 positive AML as well as cryptic deletions within the immunoglobulin IGH and T cell receptor gene (TRG alpha) complexes[4]. Importantly, these aberrations were found to be absent in CML-MBC and hence they are potentially a helpful diagnostic tool for difficult cases.

Most cases will have monosomy 7, trisomy 8 or complex karyotypes in addition to the t(9;22)(q34.1;q11.2)[5].

| Chromosome Number | Gain/Loss/Amp/LOH | Region |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | Loss | chr7 |

| 8 | Gain | chr8 |

End of V4 Section

Characteristic Chromosomal or Other Global Mutational Patterns

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: Included in this category are alterations such as hyperdiploid; gain of odd number chromosomes including typically chromosome 1, 3, 5, 7, 11, and 17; co-deletion of 1p and 19q; complex karyotypes without characteristic genetic findings; chromothripsis; microsatellite instability; homologous recombination deficiency; mutational signature pattern; etc. Details on clinical significance such as prognosis and other important information can be provided in the notes section. Please include references throughout the table. Do not delete the table.)

| Chromosomal Pattern | Molecular Pathogenesis | Prevalence -

Common >20%, Recurrent 5-20% or Rare <5% (Disease) |

Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Significance - D, P, T | Established Clinical Significance Per Guidelines - Yes or No (Source) | Clinical Relevance Details/Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE:

Co-deletion of 1p and 18q |

EXAMPLE: See chromosomal rearrangements table as this pattern is due to an unbalanced derivative translocation associated with oligodendroglioma (add reference). | EXAMPLE: Common (Oligodendroglioma) | EXAMPLE: D, P | ||

| EXAMPLE:

Microsatellite instability - hypermutated |

EXAMPLE: Common (Endometrial carcinoma) | EXAMPLE: P, T | |||

editv4:Characteristic Chromosomal Aberrations / PatternsThe content below was from the old template. Please incorporate above.

In AML, BCR-ABL1 has been described together with different class II aberrations such as CBFB-MYH11, RUNX1- RUNX1T1 and PML-RARA[1]. In AML, BCR-ABL1 seems to cooperate with several AML-specific aberrations such as inv(16), t(8;21) and myelodysplasia-related cytogenetic aberrations[1][6]. (For diagnostic purpose, note that inv(16) is not restricted to AML and can also be found in CML-MBC).

End of V4 Section

Gene Mutations (SNV/INDEL)

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: This table is not meant to be an exhaustive list; please include only genes/alterations that are recurrent or common as well either disease defining and/or clinically significant. If a gene has multiple mechanisms depending on the type or site of the alteration, add multiple entries in the table. For clinical significance, denote associations with FDA-approved therapy (not an extensive list of applicable drugs) and NCCN or other national guidelines if applicable; Can also refer to CGC workgroup tables as linked on the homepage if applicable as well as any high impact papers or reviews of gene mutations in this entity. Details on clinical significance such as prognosis and other important information such as concomitant and mutually exclusive mutations can be provided in the notes section. Please include references throughout the table. Do not delete the table.)

| Gene | Genetic Alteration | Tumor Suppressor Gene, Oncogene, Other | Prevalence -

Common >20%, Recurrent 5-20% or Rare <5% (Disease) |

Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Significance - D, P, T | Established Clinical Significance Per Guidelines - Yes or No (Source) | Clinical Relevance Details/Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE:EGFR

|

EXAMPLE: Exon 18-21 activating mutations | EXAMPLE: Oncogene | EXAMPLE: Common (lung cancer) | EXAMPLE: T | EXAMPLE: Yes (NCCN) | EXAMPLE: Exons 18, 19, and 21 mutations are targetable for therapy. Exon 20 T790M variants cause resistance to first generation TKI therapy and are targetable by second and third generation TKIs (add references). |

| EXAMPLE: TP53; Variable LOF mutations

|

EXAMPLE: Variable LOF mutations | EXAMPLE: Tumor Supressor Gene | EXAMPLE: Common (breast cancer) | EXAMPLE: P | EXAMPLE: >90% are somatic; rare germline alterations associated with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (add reference). Denotes a poor prognosis in breast cancer. | |

| EXAMPLE: BRAF; Activating mutations | EXAMPLE: Activating mutations | EXAMPLE: Oncogene | EXAMPLE: Common (melanoma) | EXAMPLE: T | ||

Note: A more extensive list of mutations can be found in cBioportal, COSMIC, and/or other databases. When applicable, gene-specific pages within the CCGA site directly link to pertinent external content.

editv4:Gene Mutations (SNV/INDEL)The content below was from the old template. Please incorporate above.

Coinciding molecular events such as NPM1 mutations have been reported[2].

| Gene | Mutation | Oncogene/Tumor Suppressor/Other | Presumed Mechanism (LOF/GOF/Other; Driver/Passenger) | Prevalence (COSMIC/TCGA/Other) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPM1 |

Other Mutations

| Type | Gene/Region/Other |

|---|---|

| Concomitant Mutations | |

| Secondary Mutations | |

| Mutually Exclusive |

End of V4 Section

Epigenomic Alterations

Not applicable

Genes and Main Pathways Involved

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: Please include references throughout the table. Do not delete the table.)

| Gene; Genetic Alteration | Pathway | Pathophysiologic Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE: BRAF and MAP2K1; Activating mutations | EXAMPLE: MAPK signaling | EXAMPLE: Increased cell growth and proliferation |

| EXAMPLE: CDKN2A; Inactivating mutations | EXAMPLE: Cell cycle regulation | EXAMPLE: Unregulated cell division |

| EXAMPLE: KMT2C and ARID1A; Inactivating mutations | EXAMPLE: Histone modification, chromatin remodeling | EXAMPLE: Abnormal gene expression program |

editv4:Genes and Main Pathways InvolvedThe content below was from the old template. Please incorporate above.

The BCR gene product has serine/threonine kinase activity and is a GTPase-activating protein for p21rac[7]. The ABL1 gene is a proto-oncogene that encodes a protein tyrosine kinase involved in a variety of cellular processes, including cell division, adhesion, differentiation, and response to stress. The activity of this protein is negatively regulated by its SH3 domain, whereby deletion of the region encoding this domain results in an oncogene[8]. The t(9,22)(q34;q11) leads to the formation of a Philadelphia chromosome and generates an active chimeric BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase. The fusion gene is created by juxtaposing the ABL1 gene on chromosome 9 (region q34) to a part of BCR (breakpoint cluster region) gene on chromosome 22 (region q11). This is a reciprocal translocation, creating an elongated chromosome 9 (der 9), and a truncated chromosome 22 (the Philadelphia chromosome, 22q-), the oncogenic BCR-ABL1 being found on the shorter derivative 22 chromosome[9][10]. This gene encodes for a BCR-ABL1 fusion protein, a tyrosine kinase. Tyrosine kinase activities are typically regulated in an auto-inhibitory manner, but the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene codes for a protein that is continuously activated, causing unregulated cell division. This is a result of the replacement of the myristoylated cap region which causes a conformational change rendering the kinase domain inactive, with a truncated portion of the BCR protein[11]. The enzyme is responsible for the uncontrolled growth of leukemic cells which survive better than normal blood cells. As a result of BCR/ABL1 variable splicing (fusion RNA and hybrid proteins), two transcripts p190 and p210 are found for BCR-ABL1 positive AML.

End of V4 Section

Genetic Diagnostic Testing Methods

Bone marrow with myeloid blasts >20% combined with detection of t(9,22) by karytoype analysis or BCR-ABL1 using FISH or reverse transcriptase-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)[1]. A graphic of the clinical path for the differential diagnosis of BCR-ABL1 positive acute myeloid leukemia and chronic myeloid leukemia-myeloid blast crisis (CML-MBC) is presented[1].

Familial Forms

Not applicable

Additional Information

Not applicable

Links

Vogel A, et al. Acute Myeloid Leukemia with BCR-ABL1. SH2017-0299. Presentation at Society for Hematopathology / European Association for Haematopathology (SH/EAHP) 2017 Workshop. https://www.sh-eahp.org/images/2017_Workshop/3_3SH-EAHP%202017_AML%20with%20BCR-ABL1_%20AV%20FINAL.pdf (accessed 29th June 2018)

References

(use the "Cite" icon at the top of the page) (Instructions: Add each reference into the text above by clicking where you want to insert the reference, selecting the “Cite” icon at the top of the wiki page, and using the “Automatic” tab option to search by PMID to select the reference to insert. If a PMID is not available, such as for a book, please use the “Cite” icon, select “Manual” and then “Basic Form”, and include the entire reference. To insert the same reference again later in the page, select the “Cite” icon and “Re-use” to find the reference; DO NOT insert the same reference twice using the “Automatic” tab as it will be treated as two separate references. The reference list in this section will be automatically generated and sorted.)

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Neuendorff, Nina Rosa; et al. (2016). "BCR-ABL-positive acute myeloid leukemia: a new entity? Analysis of clinical and molecular features". Annals of Hematology. 95 (8): 1211–1221. doi:10.1007/s00277-016-2721-z. ISSN 1432-0584. PMID 27297971.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Arber DA, et al., (2017). Acute Myeloid Leukemia, in Hematopathology, 2nd Edition. Jaffe E, Arer DA, Campo E, Harris NL, and Quintanilla-Fend L, Editors. Elsevier:Philadelphia, PA, p817-846.

- ↑ O’Donnell MR, Tallman MS, (2016). NCCN Clinical Practise Guidelines in Oncology: AML. Version 1. Available at: NCCN.org.

- ↑ Nacheva, Ellie P.; et al. (2013). "Does BCR/ABL1 positive acute myeloid leukaemia exist?". British Journal of Haematology. 161 (4): 541–550. doi:10.1111/bjh.12301. ISSN 1365-2141. PMID 23521501.

- ↑ Arber DA, et al., (2017). Acute myeloid leukaemia with recurrent genetic abnormalities, in World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Revised 4th edition. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Arber DA, Hasserjian RP, Le Beau MM, Orazi A, and Siebert R, Editors. Revised 4th Edition. IARC Press: Lyon, France, p140.

- ↑ Bacher, Ulrike; et al. (2011). "Subclones with the t(9;22)/BCR-ABL1 rearrangement occur in AML and seem to cooperate with distinct genetic alterations". British Journal of Haematology. 152 (6): 713–720. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08472.x. ISSN 1365-2141. PMID 21275954.

- ↑ Maru, Y.; et al. (1991). "The BCR gene encodes a novel serine/threonine kinase activity within a single exon". Cell. 67 (3): 459–468. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90521-y. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 1657398.

- ↑ Wang, Jean Y. J. (2014). "The capable ABL: what is its biological function?". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 34 (7): 1188–1197. doi:10.1128/MCB.01454-13. ISSN 1098-5549. PMC 3993570. PMID 24421390.

- ↑ Kurzrock, Razelle; et al. (2003). "Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias: from basic mechanisms to molecular therapeutics". Annals of Internal Medicine. 138 (10): 819–830. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-10-200305200-00010. ISSN 1539-3704. PMID 12755554.

- ↑ Melo, J. V. (1996). "The diversity of BCR-ABL fusion proteins and their relationship to leukemia phenotype". Blood. 88 (7): 2375–2384. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 8839828.

- ↑ Nagar, Bhushan; et al. (2003). "Structural basis for the autoinhibition of c-Abl tyrosine kinase". Cell. 112 (6): 859–871. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00194-6. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 12654251.

Notes

*Primary authors will typically be those that initially create and complete the content of a page. If a subsequent user modifies the content and feels the effort put forth is of high enough significance to warrant listing in the authorship section, please contact the Associate Editor or other CCGA representative. When pages have a major update, the new author will be acknowledged at the beginning of the page, and those who contributed previously will be acknowledged below as a prior author.

Prior Author(s):

*Citation of this Page: “Acute myeloid leukaemia with BCR::ABL1 fusion”. Compendium of Cancer Genome Aberrations (CCGA), Cancer Genomics Consortium (CGC), updated 02/11/2025, https://ccga.io/index.php/HAEM5:Acute_myeloid_leukaemia_with_BCR::ABL1_fusion.