HAEM4Backup:Pure Erythroid Leukemia

Primary Author(s)*

Ashwini Yenamandra PhD FACMG

Cancer Category/Type

Cancer Sub-Classification / Subtype

Pure Erythroid Leukemia (PEL) is now the only type of Acute Erythroid Leukemia (AEL).

Definition / Description of Disease

In the 2008 WHO classification, Acute Erythroid leukemia (AEL) was classified into two subtypes: Erythroleukemia (erythroid/myeloid) and Pure Erythroid Leukemia (PEL). However, in the 2016 WHO update, Erythroleukemia was merged into myelodysplastic syndrome, while PEL is now the only type of AEL[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]. PEL is a distinct entity in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system within the section of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML), Not Otherwise Specified. PEL is a rare form of acute leukemia with an aggressive clinical course and is characterized by an uncontrolled proliferation of immature erythroid precursors (proerythroblastic or undifferentiated)[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12].

Synonyms / Terminology

Also known as AML-M6b and Di Guglielmo syndrome due to the recognition of the work of Di Guglielmo[1][2].

Epidemiology / Prevalence

PEL is extremely rare with a small number of reported cases, accounting for 3-5% of AML cases[1][2][10]. Median survival is usually three months[12].

Clinical Features

PEL has an aggressive clinical course with neoplastic proliferation of immature erythroid precursor (proerythroblastic or undifferentiated) cells. Average survival rate is three months[1][10]. PEL is characterized by neoplastic proliferation composed of >80% immature erythroid precursors of which proerythroblasts constitute ≥30%[12]. Clinical features include profound anemia, circulating erythroblasts, pancytopenia, extensive bone marrow involvement, fatigue, infections, weight loss, fever, night sweats, hemoglobin level under 10.0 g/dL, and thrombocytopenia[1][10].

Sites of Involvement

Bone marrow, Blood

Morphologic Features

PEL is characterized by medium to large erythroblasts with round nuclei, fine chromatin and one or more nucleoli (proerythroblast). Cytoplasm is deeply basophilic, often granular with demarcated vacuoles and are often Periodic-Acid-Schiff stain (PAS) positive. Blasts can be small and may resemble lymphoblasts[1]. Cells are usually negative for Myeloperoxidase (MPO) and Sudan Black (SBB). Bone marrow biopsy may have undifferentiated cells[1].

Immunophenotype

Differentiated PEL may express Glycophorin and hemoglobin A, absence of myeloperoxidase (MPO) and other myeloid markers[1]. Blasts are negative for HLA-Dr and CD34 but positive for CD117[1]. Immature forms can be negative for Glycophorin or weekly expressed. Positive for Carbonic anhydrase 1, Gero antobody against the Gerbich blood group or CD36 especially at earlier stages of differentiation. CD41 and CD61 are negative[1][12].

| Finding | Marker |

|---|---|

| Positive (universal) | Hemoglobin A, Glycophorin A, Spectrin, ABH blood group antigens, and HLA-DR |

| Positive (subset) | CD13, CD33, CD34, CD117 (KIT), and MPO, Gerbich blood group (Gero) antibody, carbonic anhydrase 1, and CD36, CD41 and CD61 |

| Negative (universal) | Myeloid-associated markers such as MPO,CD13,CD33,CD61, B and T Cell markers -CD10, CD19, CD79a, CD2, CD3, CD5, monocytic markers CD11c CD14

Megakaryoblastic markers: CD61, Others: CD34, anti-kappa, anti-lambda, CD45 |

| Negative (subset) | HLA-DR, CD34, Glycophorin A |

Chromosomal Rearrangements (Gene Fusions)

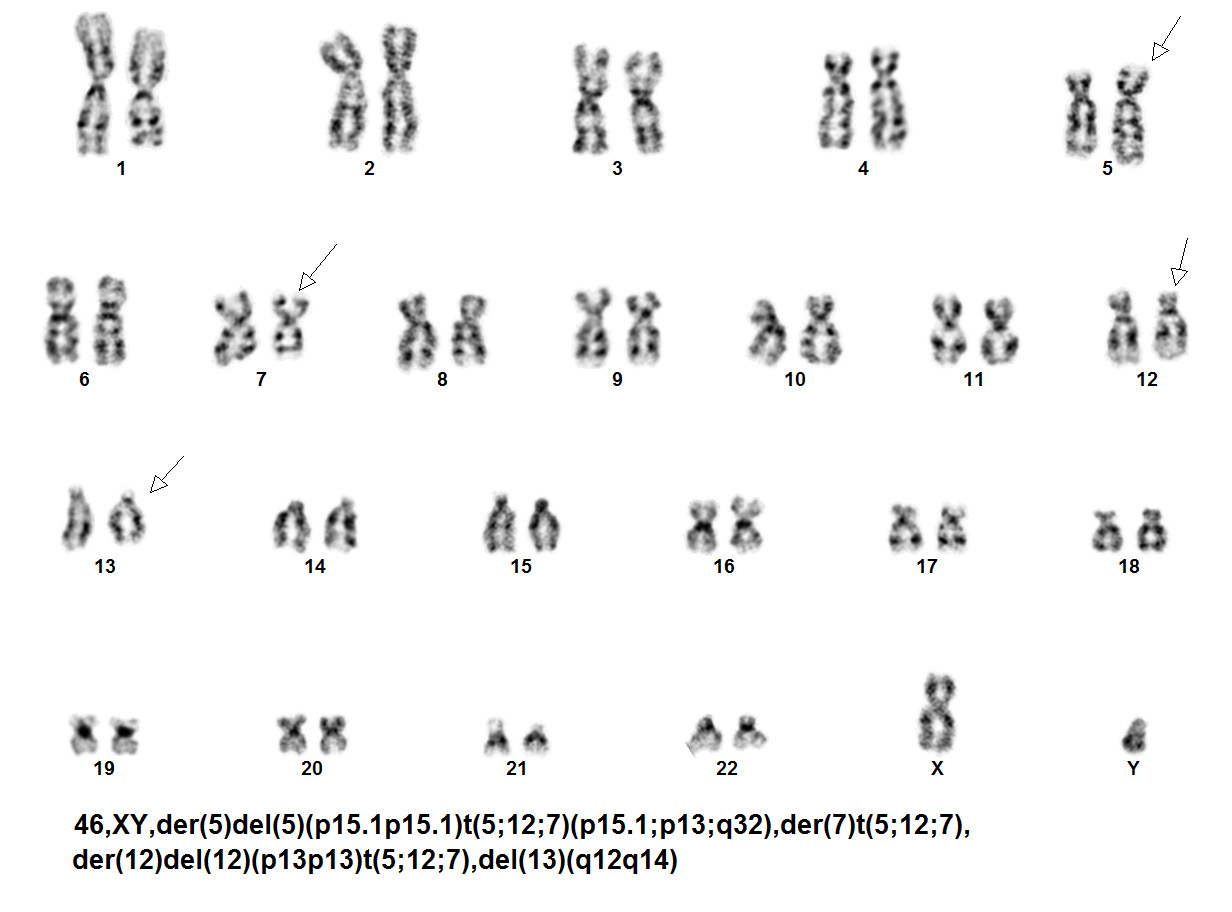

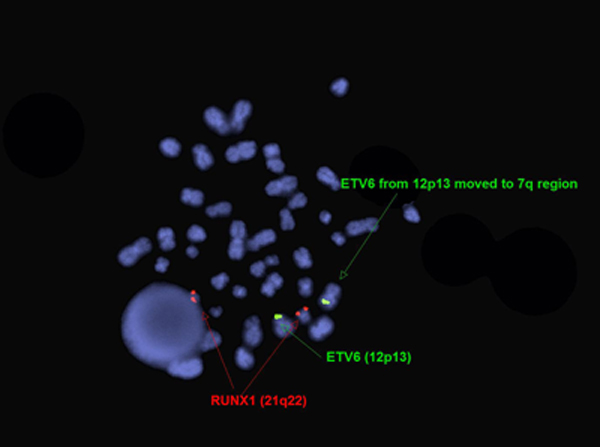

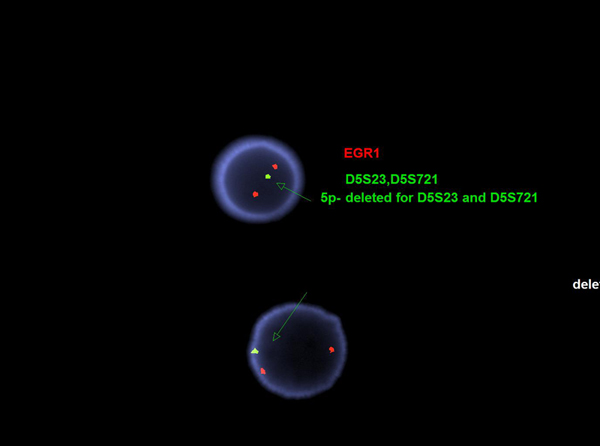

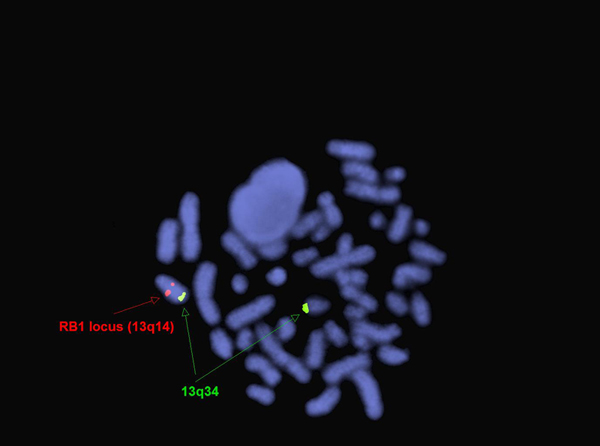

The genetic abnormalities that have been identified in PEL are similar to that of AML and MDS and consists of complex chromosomal abnormalities including -5/del(5q), -7/del(7q), +8 and/or RUNX1 and TP53 mutations[1]. Rearrangement of NFIA-CBFA2T3 with t(1;16)(p31;q24) and MYND8-RELA with t(11;20)(p11;q11) have been reported in rare cases[10]. A complex karyotype with 46,XY,der(5)del(5)(p15.1p15.1)t(5;12;7)(p15.1;p13;q32),der(7)t(5;12;7),der(12)del(12)p13p13)t(5;12;7),del(13)(q12q14) was reported in a two year old boy with PEL[11].

| Chromosomal Rearrangement | Genes in Fusion (5’ or 3’ Segments) | Pathogenic Derivative | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| t(1;16)(p31;q24) | 5’NFIA/ 3’CBFA2T3 | der(16) | Rare |

| t(11;20)(p11;q11) | 5’MYND8/ 3’RELA | der(11) | Rare |

Characteristic Chromosomal Aberrations / Patterns

Genomic Gain/Loss/LOH

Not Applicable

| Chromosome Number | Gain/Loss/Amp/LOH | Region |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | Loss | Whole chromosome or q-arm |

| 7 | Loss | Whole chromosome or q-arm |

| 8 | Gain | Whole chromosome |

| 17 | Loss | P-arm |

Gene Mutations (SNV/INDEL)

JAK2, FLT3, RAS, NPM1, and CEBPA mutations have been reported to be rare in PEL[10][11][12]. Intraclonal heterogeneity and founder mutations of TP53 were reported in 92% (11 out of 12 cases) while co-occurrence of TP53 mutation and deletion due to chromosome 17p abnormalities were detected in 73% of PEL cases[13].

| Gene | Mutation | Oncogene/Tumor Suppressor/Other | Presumed Mechanism (LOF/GOF/Other; Driver/Passenger) | Prevalence (COSMIC/TCGA/Other) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE TP53 | EXAMPLE R273H | EXAMPLE Tumor Suppressor | EXAMPLE LOF | EXAMPLE 20% |

Other Mutations

| Type | Gene/Region/Other |

|---|---|

| Concomitant Mutations | EXAMPLE IDH1 R123H |

| Secondary Mutations | EXAMPLE Trisomy 7 |

| Mutually Exclusive | EXAMPLE EGFR Amplification |

Epigenomics (Methylation)

Not Applicable

Genes and Main Pathways Involved

The molecular mechanism is not completely understood.

Diagnostic Testing Methods

Morphology and IHC.

Clinical Significance (Diagnosis, Prognosis and Therapeutic Implications)

PEL has rapid and aggressive clinical course. Patients with PEL are treated similar to other types of AML. Stem cell transplantation (SCT) may have an improvement in the outcome of the disease. No therapeutic agents for specific target pathways are currently available[3].

Familial Forms

Not Applicable

Other Information

Differential Diagnosis: PEL without morphological differentiation of erythroid maturation can be difficult to distinguish from megakaryoblastic leukemia (AML), ALL or lymphoma. The erythroid precursor immunophenotype helps in the diagnosis. Some cases can be complex with concurrent erythroid megakaryocytic involvement[1].

Links

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Arber DA, et al., (2008). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th edition. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW, Editors. IARC Press: Lyon, France, p135-136.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Qiu, Shaowei; et al. (2017). "An analysis of 97 previously diagnosed de novo adult acute erythroid leukemia patients following the 2016 revision to World Health Organization classification". BMC cancer. 17 (1): 534. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3528-6. ISSN 1471-2407. PMC 5550989. PMID 28793875.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Zuo, Zhuang; et al. (2010). "Acute erythroid leukemia". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 134 (9): 1261–1270. doi:10.1043/2009-0350-RA.1. ISSN 1543-2165. PMID 20807044.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Arber, Daniel A.; et al. (2016). "The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia". Blood. 127 (20): 2391–2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. ISSN 1528-0020. PMID 27069254.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Zuo, Zhuang; et al. (2012). "Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with erythroid predominance exhibits clinical and molecular characteristics that differ from other types of AML". PloS One. 7 (7): e41485. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041485. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3402404. PMID 22844482.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Grossmann, V.; et al. (2013). "Acute erythroid leukemia (AEL) can be separated into distinct prognostic subsets based on cytogenetic and molecular genetic characteristics". Leukemia. 27 (9): 1940–1943. doi:10.1038/leu.2013.144. ISSN 1476-5551. PMID 23648669.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Porwit, Anna; et al. (2011). "Acute myeloid leukemia with expanded erythropoiesis". Haematologica. 96 (9): 1241–1243. doi:10.3324/haematol.2011.050526. ISSN 1592-8721. PMC 3166090. PMID 21880638.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Hasserjian, Robert P.; et al. (2010). "Acute erythroid leukemia: a reassessment using criteria refined in the 2008 WHO classification". Blood. 115 (10): 1985–1992. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-09-243964. ISSN 1528-0020. PMC 2942006. PMID 20040759.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Wang, Sa A.; et al. (2015). "Acute Erythroleukemias, Acute Megakaryoblastic Leukemias, and Reactive Mimics: A Guide to a Number of Perplexing Entities". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 144 (1): 44–60. doi:10.1309/AJCPRKYAT6EZQHC7. ISSN 1943-7722. PMID 26071461.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Wang, Wei; et al. (2017). "Pure erythroid leukemia". American Journal of Hematology. 92 (3): 292–296. doi:10.1002/ajh.24626. ISSN 1096-8652. PMID 28006859.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 A, Yenamandra (2016). "Acute Erythroblastic Leukemia (AEL): A Rare Subset of De Novo AML with A Complex Rearrangement Involving ETV6 Locus and Loss of RB1 Locus". International Clinical Pathology Journal. 2 (2). doi:10.15406/icpjl.2016.02.00032.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Fs, Khan (2017). "Pure Erythroid Leukemia: The Sole Acute Erythroid Leukemia". International Journal of Bone Marrow Research. 1 (1): 001–005. doi:10.29328/journal.ijbmr.1001001.

- ↑ Montalban-Bravo, Guillermo; et al. (2017). "More than 1 TP53 abnormality is a dominant characteristic of pure erythroid leukemia". Blood. 129 (18): 2584–2587. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-11-749903. ISSN 1528-0020. PMC 5418636. PMID 28246192.

Notes

*Primary authors will typically be those that initially create and complete the content of a page. If a subsequent user modifies the content and feels the effort put forth is of high enough significance to warrant listing in the authorship section, please contact the CCGA coordinators (contact information provided on the homepage). Additional global feedback or concerns are also welcome.

- Translocation

- Translocation Chromosome 1

- Translocation Chromosome 16

- Translocation Chromosome 11

- Translocation Chromosome 20

- Structural Chromosome Abnormalities

- Structural Chromosome Abnormalities in AML

- Structural Abnormalities Chromosome 1

- Structural Abnormalities Chromosome 16

- Structural Abnormalities Chromosome 11

- Structural Abnormalities Chromosome 20

- Loss Chromosome 5

- Loss Chromosome 7

- Loss Chromosome 17

- Gain Chromosome 8

- Fusion Genes in AML

- Fusion Genes N

- Fusion Genes C

- Fusion Genes M

- Fusion Genes R

- Oncogenes in AML

- Oncogenes R

- Tumor Suppressor Genes in AML

- Tumor Suppressor Genes T

- Recently Added Pages