Atypical Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (aCML), BCR-ABL1 Negative

editPREVIOUS EDITIONThis page from the 4th edition of Haematolymphoid Tumours is being updated. See 5th edition Table of Contents.

Primary Author(s)*

Linsheng Zhang, MD, PhD

Cancer Category/Type

Myeloid neoplasm

Cancer Sub-Classification / Subtype

Myelodysplastic/Myeloproliferative Neoplasm

Definition / Description of Disease

Atypical chronic myeloid leukemia, BCR-ABL1-negative (aCML) presents with myelodysplastic as well as myeloproliferative features at the time of disease onset[1][2]. The characteristic finding is blood leukocytosis with increase of dysplastic neutrophils and immature granulocytes. Bone marrow shows multilineage dysplasia.

- Before the diagnosis of aCML can be rendered, myeloid neoplasms with well defined genetic abnormalities such as BCR-ABL1 fusion; rearrangement of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, FGFR1, or PCM1-JAK2 must be ruled out.

- Myeloid neoplasm with features of aCML developed after chemo or radiation therapy is classified as therapy-related myeloid neoplasm.

Synonyms / Terminology

Atypical chronic myeloid leukemia, Philadelphia chromosome-negative (Ph-)

Atypical chronic myeloid leukemia, BCR-ABL1-negative

Epidemiology / Prevalence

The incidence of aCML is low; it is estimated that there are 1-2 aCML cases for every 100 cases of BCR-ABL1-positive chronic myeloid leukemia[3][4].

The median patient age at diagnosis is in the seventh or eighth decade of life[4][5][6]. Rare cases of aCML has also been reported in teenagers. The reported male-to female ratio is approximately 1:1[1].

Clinical Features

The primary symptoms are related to splenomegaly and blood cell changes like anemia and/or thrombocytopenia[5][7][6].

Sites of Involvement

- Blood and bone marrow are always involved.

- Involvement of spleen and liver is common.

Morphologic Features

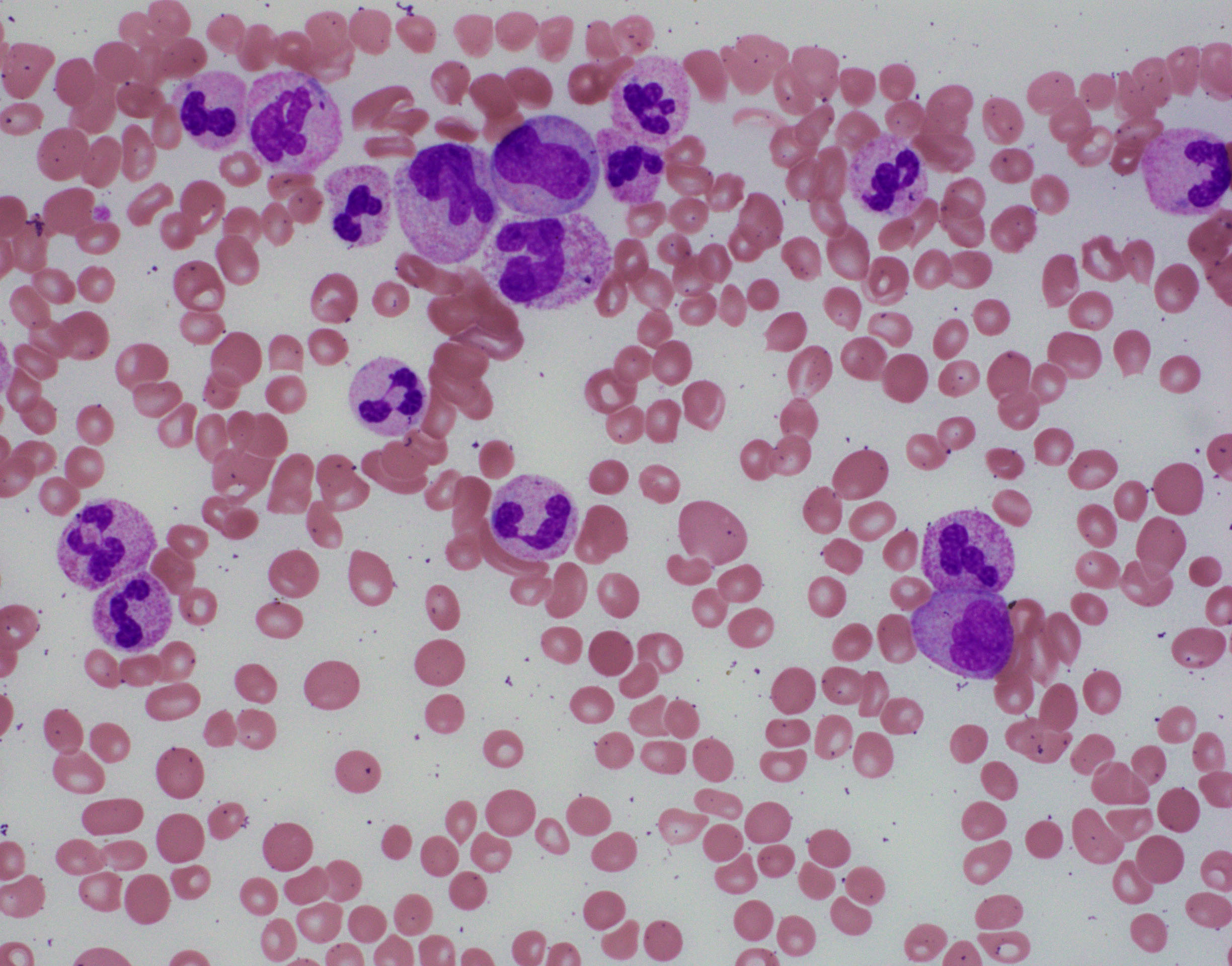

BLOOD:

- The white blood cell count (WBC) ≥13 x 109/L, cases >300 x 109/L have been reported.

- Immature granulocytes, including promyelocytes, myelocytes, and metamyelocytes ≥10% of the leukocytes.

- Monocytes <10%.

- Mild basophilia.

- Dysplastic features observed in granulocytes:

- Acquired Pelger-Huët anomaly

- Other nuclear abnormalities (hypersegmentation with abnormally clumped nuclear chromatin or bizarrely segmented nuclei)

- Multiple nuclear projections

- Abnormal cytoplasmic granularity (usually hypogranularity).

- The syndrome of abnormal chromatin clumping is considered to be a morphologic variant of aCML[8].

- Neutrophil nuclei show large well-separated blocks of heterochromatin and euchromatin

- Anemia and thrombocytopenia are common.

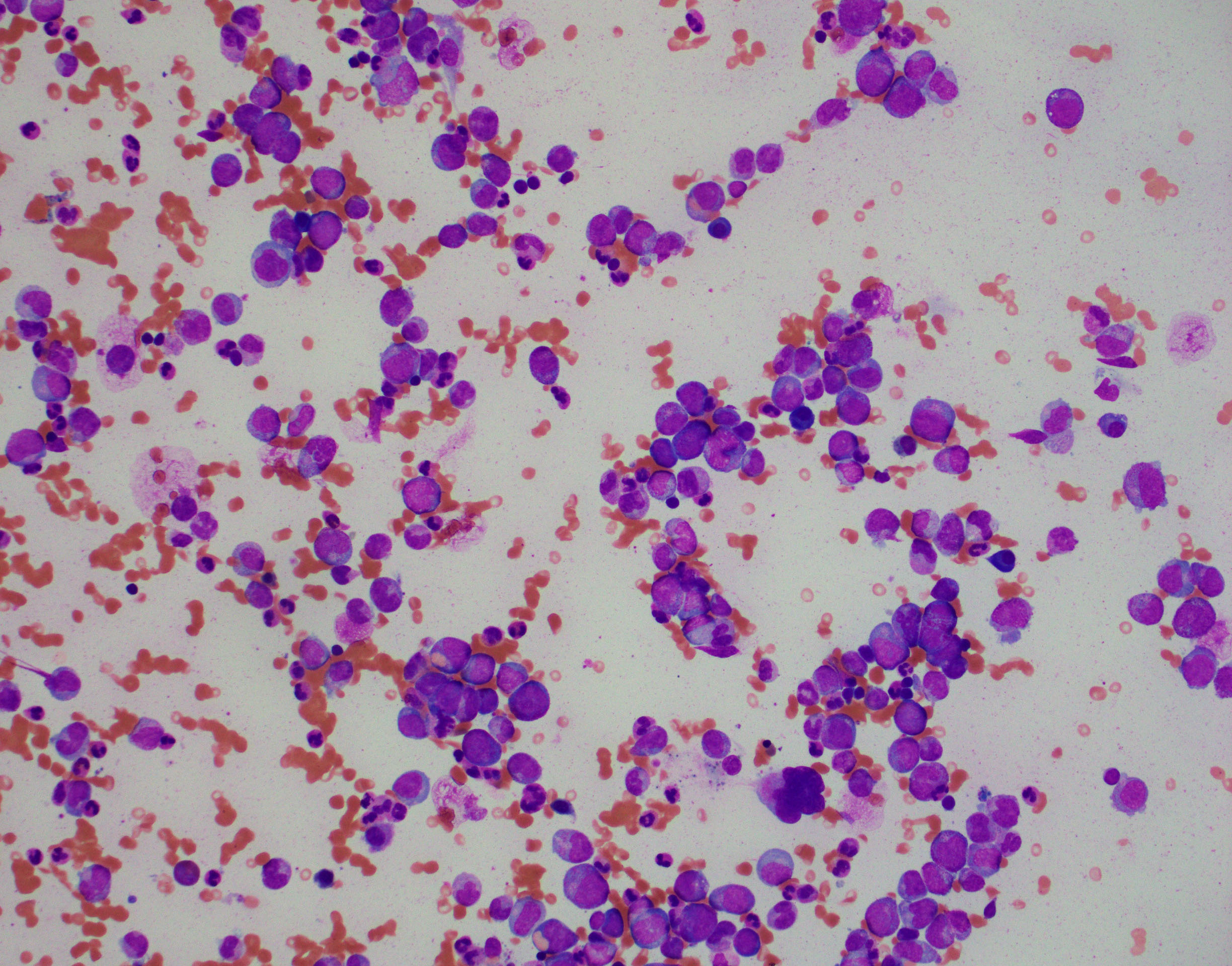

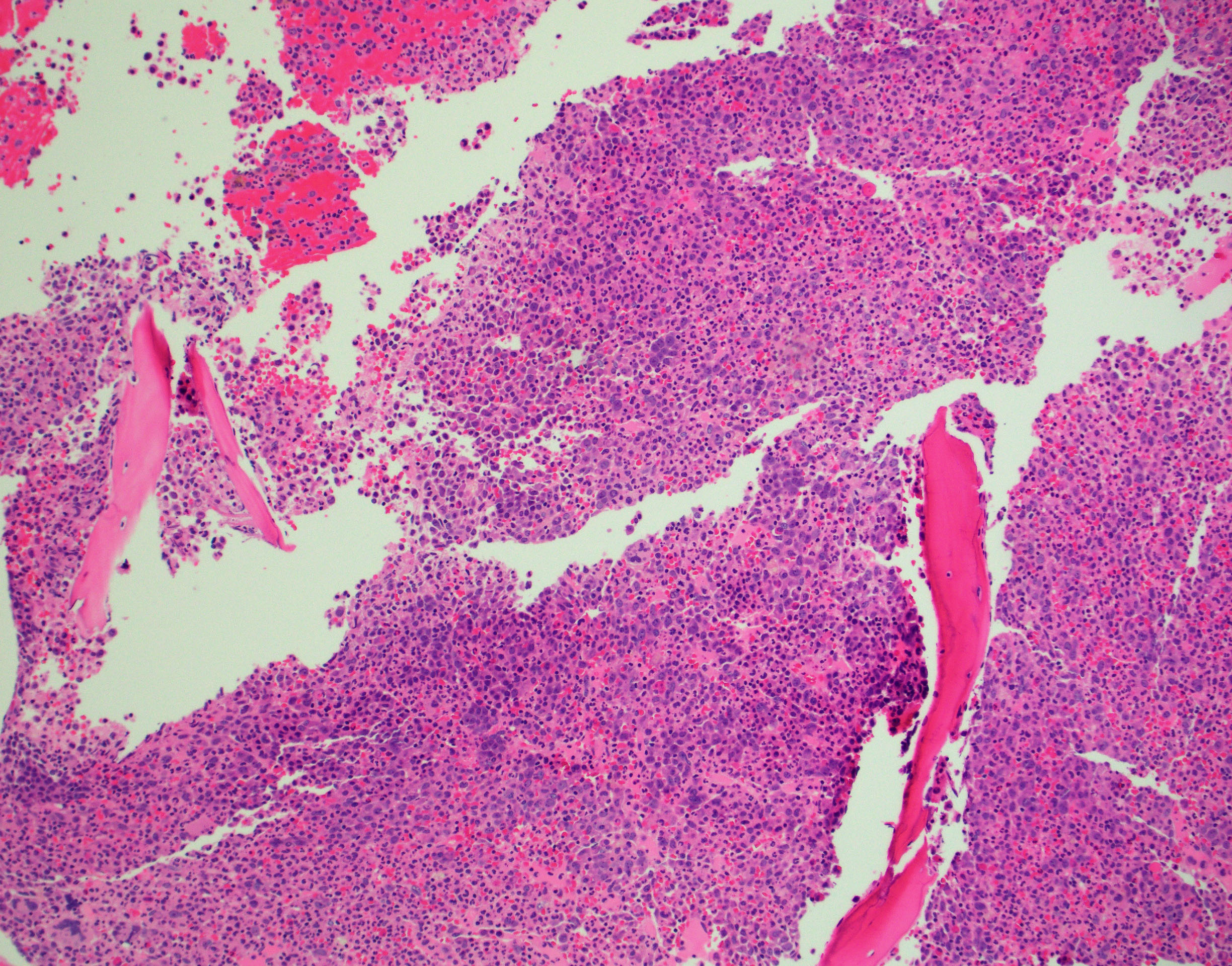

BONE MARROW:

- Hypercellular with markedly increased myeloid-to-erythroid ratio (usually >10:1)

- Features of trilineage dysplasia

- Dyserythropoiesis is present in about 40% of cases.

- Dysgranulopoiesis with the changes in the neutrophil lineage similar to those in the blood.

- Megakaryocytes quantitatively variable, usually normal or increased, frequently with dysmegakaryopoiesis, including micromegakaryocytes and small megakaryocytes with hypolobated nuclei.

- Mild fibrosis seen in some cases; may be more conspicuous with disease progression.

By definition, blasts <20% of blood leukocytes (usually <5%) and <20% of bone marrow nucleated cells.

Immunophenotype

No specific immunophenotypic characteristics (flow cytometric analysis of blood and bone marrow usually report as normal, except mildly increased myeloblasts in some cases).

Chromosomal Rearrangements (Gene Fusions)

None.

Characteristic Chromosomal Aberrations / Patterns

None.

Genomic Gain/Loss/LOH

Karyotypic abnormalities are reported in as many as 80% of cases.

- Trisomy 8 and del(20q) most common.

- Abnormalities of chromosomes 13, 14, 17, 19 and 12 are also common [5][6].

- Isolated isochromosome 17q rare (most present with features of CMML instead of aCML).

Gene Mutations (SNV/INDEL)

| Gene | Mutation | Oncogene/Tumor Suppressor/Other | Presumed Mechanism (LOF/GOF/Other; Driver/Passenger) | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SETBP1 | D868N, S869N, G870S, I871T and D880N[9] | Other: conferring self-renewal capability to myeloid progenitors[10] | GOF | 25-38%[11][12] |

Other Mutations

| Gene/Mutation | Prevalence[4] |

|---|---|

| RAS (KRAS/NRAS) | 35% |

| ETNK1: H243Y and N244S | 8.8%[13] |

| JAK2: V617F | 7% |

| CSF3R | <10% |

| CALR | <10% |

| APC2 | 6%[12] |

Mutations in TET2, ASXL1, EZH2 and SRSF2 (overlapping with CMML) are not uncommon in aCML[14].

Epigenomics (Methylation)

Not well studied yet.

Genes and Main Pathways Involved

Frequently involved:

- Cell proliferation and survival (SETBP1)

Less commonly involved:

- JAK/STAT pathway (JAK2)

- PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK (CSF3R)

Diagnostic Testing Methods

Blood cell counts and blood smear review (differential cell counts and dysplastic features).

Bone marrow aspirate smear review and biopsy histopathology (abnormal maturation pattern, blast percentage, etc.).

Molecular/genetic studies are of critical importance to establish clonal evidence and rule out other entities with well defined genetic abnormalities.

- Chromosome analysis

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to rule out PDGFRA, PDGFRB or FGFR1 rearrangement, BCR-ABL1 and PCM1-JAK2 fusion.

- Next generation sequencing-based mutation profiling to detect mutations supporting a clonal process.

Clinical Significance (Diagnosis, Prognosis and Therapeutic Implications)

Genetic abnormalities and mutations in related genes provide evidence of a clonal process to support a neoplastic process. However, they are not specific for aCML.

The prognostic value of molecular/genetic abnormalities are not well studied yet.

Approximately 20-40% of aCML evolves to acute myeloid leukemia[4]; most of the remaining patients die of marrow failure[7][15].

Predictors of worse prognosis:

- Age > 65 years

- Female sex

- White blood cell count > 50 x 109/L, thrombocytopenia and hemoglobin level < 10 g/dL[15].

- Increased blasts in blood and/or bone marrow.

Familial Forms

None

Other Information

None

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Orazi A, et al., (2017). Atypical chronic myeloid leukaemia, BCR-ABL1-negative, in World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Revised 4th edition. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Arber DA, Hasserjian RP, Le Beau MM, Orazi A, and Siebert R, Editors. IARC Press: Lyon, France, p87-89.

- ↑ Czader, M and Orazi, A. Chapter 45. Myelodysplastic/Myeloproliferative Neoplasms and Related Diseases. In Orazi A, Foucar K, Knowles DM. eds. Knowles Neoplastic Hematopathology. Riverwoods, IL: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2013:1148-1150.

- ↑ A, Orazi; et al. (2008). "The Myelodysplastic/Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Myeloproliferative Diseases With Dysplastic Features". PMID 18480833.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Sa, Wang; et al. (2014). "Atypical Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Is Clinically Distinct From Unclassifiable Myelodysplastic/Myeloproliferative Neoplasms". doi:10.1182/blood-2014-02-553800. PMC 4067498. PMID 24627528.CS1 maint: PMC format (link)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Jm, Hernández; et al. (2000). "Clinical, Hematological and Cytogenetic Characteristics of Atypical Chronic Myeloid Leukemia". PMID 10847463.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 P, Martiat; et al. (1991). "Philadelphia-negative (Ph-) Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML): Comparison With Ph+ CML and Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia. The Groupe Français De Cytogénétique Hématologique". PMID 2070054.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 R, Kurzrock; et al. (2001). "BCR Rearrangement-Negative Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Revisited". PMID 11387365.

- ↑ Brizard, A.; et al. (1989). "THREE CASES OF MYELODYSPLASTIC-MYELOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDER WITH ABNORMAL CHROMATIN CLUMPING IN GRANULOCYTES". British Journal of Haematology. 72 (2): 294–295. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.1989.tb07703.x. ISSN 0007-1048.

- ↑ R, Acuna-Hidalgo; et al. (2017). "Overlapping SETBP1 Gain-Of-Function Mutations in Schinzel-Giedion Syndrome and Hematologic Malignancies". doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006683. PMC 5386295. PMID 28346496.CS1 maint: PMC format (link)

- ↑ Oakley, Kevin; et al. (2012). "Setbp1 promotes the self-renewal of murine myeloid progenitors via activation of Hoxa9 and Hoxa10". Blood. 119 (25): 6099–6108. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-10-388710. ISSN 0006-4971. PMC 3383018. PMID 22566606.CS1 maint: PMC format (link)

- ↑ Mughal, T. I.; et al. (2015). "An International MDS/MPN Working Group's perspective and recommendations on molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical characterization of myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms". Haematologica. 100 (9): 1117–1130. doi:10.3324/haematol.2014.114660. ISSN 0390-6078. PMC 4800699. PMID 26341525.CS1 maint: PMC format (link)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Palomo, Laura; et al. (2020). "Molecular landscape and clonal architecture of adult myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms". Blood. doi:10.1182/blood.2019004229. ISSN 0006-4971.

- ↑ Gambacorti-Passerini, Carlo B.; et al. (2015). "Recurrent ETNK1 mutations in atypical chronic myeloid leukemia". Blood. 125 (3): 499–503. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-06-579466. ISSN 0006-4971.

- ↑ Faisal, Muhammad; et al. (2019). "Comprehensive mutation profiling and mRNA expression analysis in atypical chronic myeloid leukemia in comparison with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia". Cancer Medicine. 8 (2): 742–750. doi:10.1002/cam4.1946. PMC 6382710. PMID 30635983.CS1 maint: PMC format (link)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 M, Breccia; et al. (2006). "Identification of Risk Factors in Atypical Chronic Myeloid Leukemia". PMID 17043019.

Notes

*Primary authors will typically be those that initially create and complete the content of a page. If a subsequent user modifies the content and feels the effort put forth is of high enough significance to warrant listing in the authorship section, please contact the CCGA coordinators (contact information provided on the homepage). Additional global feedback or concerns are also welcome.