Difference between revisions of "GTS5:Turner syndrome"

Templates/files updated (unreviewed pages in bold): GTS5:Turner syndrome, File:I(X)(q10).tif, File:46,X,psu idic(X)(q13.2).png, File:46,X,del(X)(p21.1).png, File:46,X,del(X)(q21.3).png, File:FISH for turner syndrome.tif, File:Interphase FISH for turner syndrome.tif, File:SRY in 45,X-46,XY.tif, File:Interphase SRY.tif

| [checked revision] | [pending revision] |

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Under Construction}} | {{Under Construction}} | ||

| − | <span style="color:#0070C0">(''General Instructions – The focus of these pages is the clinically significant genetic alterations in each disease type. This is based on up-to-date knowledge from multiple resources such as PubMed and the WHO classification books. The CCGA is meant to be a supplemental resource to the WHO classification books; the CCGA captures in a continually updated wiki- | + | <span style="color:#0070C0">(''General Instructions – The focus of these pages is the clinically significant genetic alterations in each disease type. This is based on up-to-date knowledge from multiple resources such as PubMed and the WHO classification books. The CCGA is meant to be a supplemental resource to the WHO classification books; the CCGA captures in a continually updated wiki-style manner the current genetics/genomics knowledge of each disease, which evolves more rapidly than books can be revised and published. If the same disease is described in multiple WHO classification books, the genetics-related information for that disease will be consolidated into a single main page that has this template (other pages would only contain a link to this main page). Use [https://www.genenames.org/ <u>HUGO-approved gene names and symbols</u>] (italicized when appropriate), [https://varnomen.hgvs.org/ <u>HGVS-based nomenclature for variants</u>], as well as generic names of drugs and testing platforms or assays if applicable. Please complete tables whenever possible and do not delete them (add N/A if not applicable in the table and delete the examples); to add (or move) a row or column in a table, click nearby within the table and select the > symbol that appears. Please do not delete or alter the section headings. The use of bullet points alongside short blocks of text rather than only large paragraphs is encouraged. Additional instructions below in italicized blue text should not be included in the final page content. Please also see'' </span><u>''[[Author_Instructions]]''</u><span style="color:#0070C0"> ''and [[Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)|<u>FAQs</u>]] as well as contact your [[Leadership|<u>Associate Editor</u>]] or [mailto:CCGA@cancergenomics.org <u>Technical Support</u>].)''</span> |

==Primary Author(s)*== | ==Primary Author(s)*== | ||

| − | + | Kathleen M. Bone, PhD, Medical College of Wisconsin | |

==WHO Classification of Disease== | ==WHO Classification of Disease== | ||

| − | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

!Structure | !Structure | ||

| Line 10: | Line 9: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Book | |Book | ||

| − | | | + | |Genetic Tumor Syndromes (5th ed.) |

|- | |- | ||

|Category | |Category | ||

| − | | | + | |DNA repair and genomic instability |

|- | |- | ||

|Family | |Family | ||

| − | | | + | |Chromosomal and non-dysjunction (aneuploidy) syndromes |

|- | |- | ||

|Type | |Type | ||

| − | | | + | |N/A |

|- | |- | ||

|Subtype(s) | |Subtype(s) | ||

| − | | | + | |Turner Syndrome |

|} | |} | ||

==Related Terminology== | ==Related Terminology== | ||

| − | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ | |+ | ||

|Acceptable | |Acceptable | ||

| − | | | + | |45,X syndrome; Ullrich-Turner syndrome |

|- | |- | ||

|Not Recommended | |Not Recommended | ||

| − | | | + | |45,XO syndrome |

|} | |} | ||

==Definition/Description of Disease== | ==Definition/Description of Disease== | ||

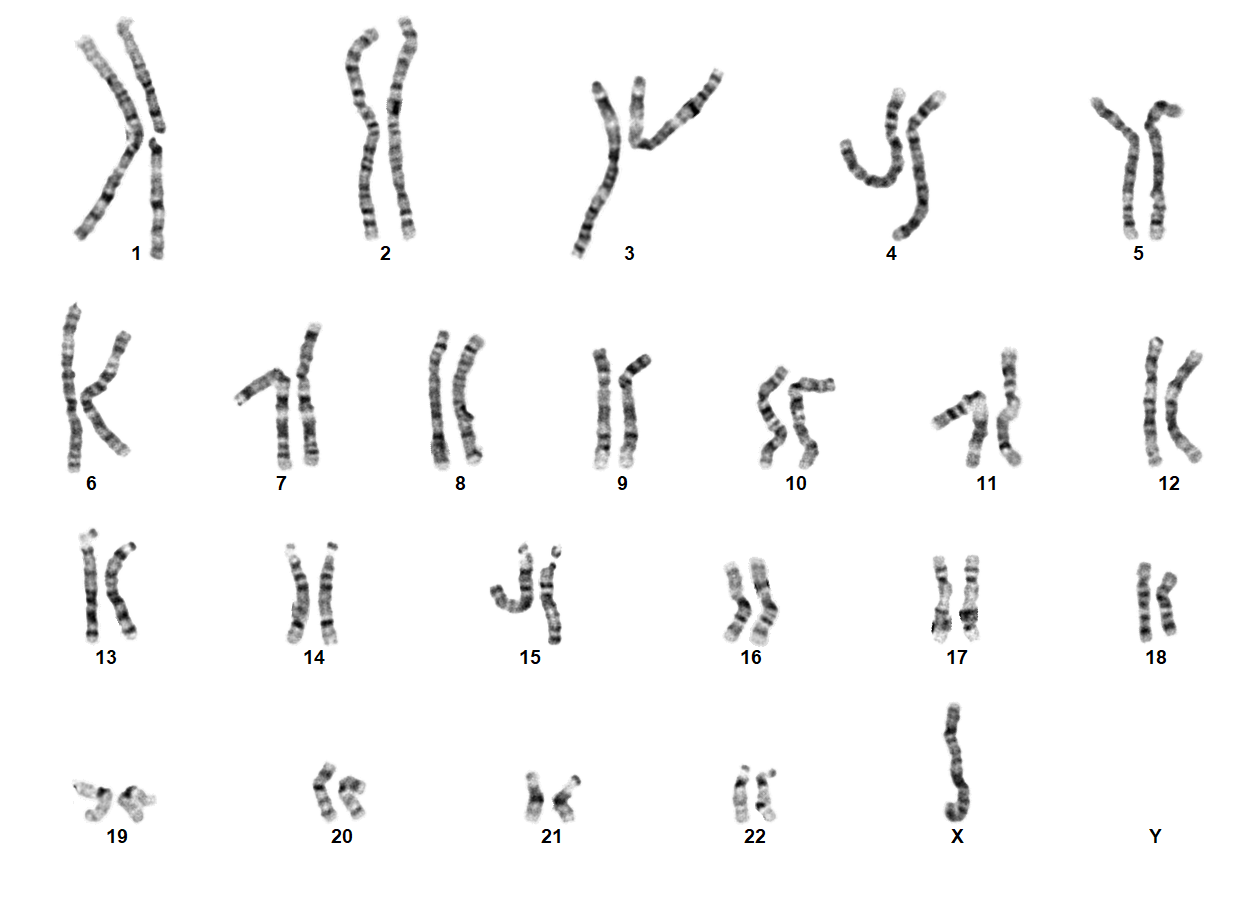

| − | + | Turner Syndrome (TS) is a rare chromosomal disorder resulting from complete or partial loss of the second sex chromosome. The most common clinical manifestations include short stature, ovarian failure, primary or secondary amenorrhea associated with hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, congenital lymphedema of the hands and feet, Madelung deformity of the forearm and wrist, webbed neck, cardiac anomalies such as coarctation of the aorta, bicuspid aortic valves, mitral valve prolapse, hypertension, ischemic heart disease and arteriosclerosis, impaired glucose tolerance, thyroid disease and hearing loss.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Gravholt|first=Claus H.|date=2005-11|title=Clinical practice in Turner syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16929365|journal=Nature Clinical Practice. Endocrinology & Metabolism|volume=1|issue=1|pages=41–52|doi=10.1038/ncpendmet0024|issn=1745-8366|pmid=16929365}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bondy|first=Carolyn A.|last2=Bakalov|first2=Vladimir K.|date=2006-07|title=Investigation of cardiac status and bone mineral density in Turner syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16624607|journal=Growth hormone & IGF research: official journal of the Growth Hormone Research Society and the International IGF Research Society|volume=16 Suppl A|pages=S103–108|doi=10.1016/j.ghir.2006.03.008|issn=1096-6374|pmid=16624607}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Dhooge|first=Ingeborg J. M.|last2=De Vel|first2=E.|last3=Verhoye|first3=C.|last4=Lemmerling|first4=M.|last5=Vinck|first5=B.|date=2005-03|title=Otologic disease in turner syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15793396|journal=Otology & Neurotology: Official Publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology|volume=26|issue=2|pages=145–150|doi=10.1097/00129492-200503000-00003|issn=1531-7129|pmid=15793396}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Güngör|first=N.|last2=Böke|first2=B.|last3=Belgin|first3=E.|last4=Tunçbilek|first4=E.|date=2000-10|title=High frequency hearing loss in Ullrich-Turner syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11039128|journal=European Journal of Pediatrics|volume=159|issue=10|pages=740–744|doi=10.1007/pl00008338|issn=0340-6199|pmid=11039128}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Zinn|first=A. R.|last2=Tonk|first2=V. S.|last3=Chen|first3=Z.|last4=Flejter|first4=W. L.|last5=Gardner|first5=H. A.|last6=Guerra|first6=R.|last7=Kushner|first7=H.|last8=Schwartz|first8=S.|last9=Sybert|first9=V. P.|date=1998-12|title=Evidence for a Turner syndrome locus or loci at Xp11.2-p22.1|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9837829|journal=American Journal of Human Genetics|volume=63|issue=6|pages=1757–1766|doi=10.1086/302152|issn=0002-9297|pmc=1377648|pmid=9837829}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Sävendahl|first=L.|last2=Davenport|first2=M. L.|date=2000-10|title=Delayed diagnoses of Turner's syndrome: proposed guidelines for change|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11035820|journal=The Journal of Pediatrics|volume=137|issue=4|pages=455–459|doi=10.1067/mpd.2000.107390|issn=0022-3476|pmid=11035820}}</ref> Despite considerable phenotypic variability, short stature and gonadal dysgenesis are the most consistent findings. While individuals with TS may experience impairments in nonverbal developmental skills, they generally have normal intellectual ability.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kesler|first=Shelli R.|date=2007-07|title=Turner syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17562588|journal=Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America|volume=16|issue=3|pages=709–722|doi=10.1016/j.chc.2007.02.004|issn=1056-4993|pmc=2023872|pmid=17562588}}</ref> TS should be suspected prenatally when a prenatal ultrasound reveals fetal hydrops, cystic hygroma, or cardiac defects. Approximately 50% of TS patients have monosomy X (45,X), while the remaining 50% exhibit various structural abnormalities of the X chromosome or mosaicism with a normal female or normal male cell line. | |

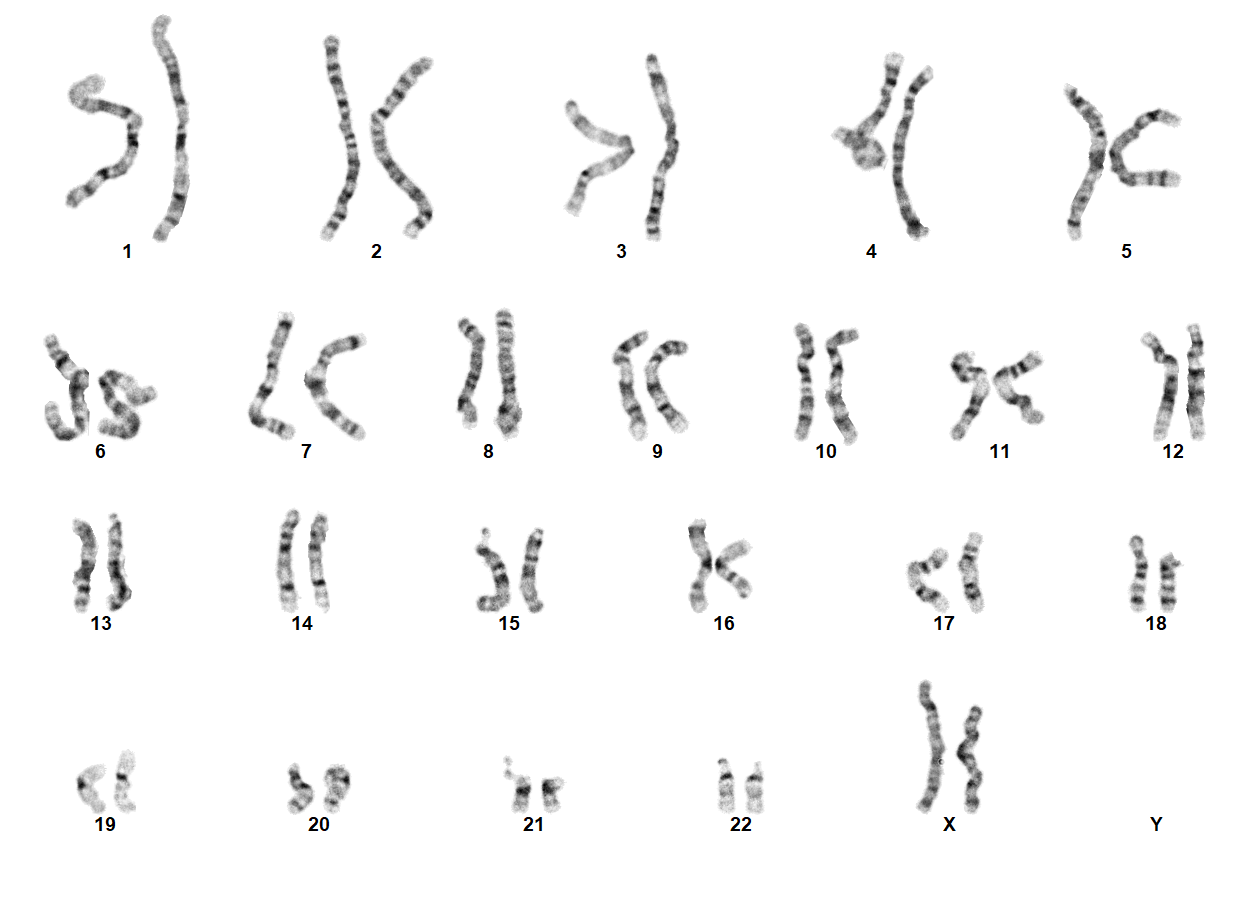

| + | [[File:45,X.png|center|thumb|G-banded chromosome analysis of a PHA-stimulated peripheral blood specimen from a patient with Turner Syndrome and a 45,X karyotype; Courtesy of Wisconsin Diagnostics Laboratories]] | ||

| + | [[File:Ring(X).tif|center|thumb|G-banded chromosome analysis of a PHA-stimulated peripheral blood specimen from a patient with variant Turner syndrome and a karyotype of 46,X,r(X)(p21q22)/45,X; Courtesy of Wisconsin Diagnostics Laboratories]] | ||

| + | [[File:I(X)(q10).tif|center|thumb|G-banded chromosome analysis of a PHA-stimulated peripheral blood specimen from a patient with variant Turner syndrome and a karyotype of 46,X,i(X)(q10); Courtesy of Wisconsin Diagnostics Laboratories]] | ||

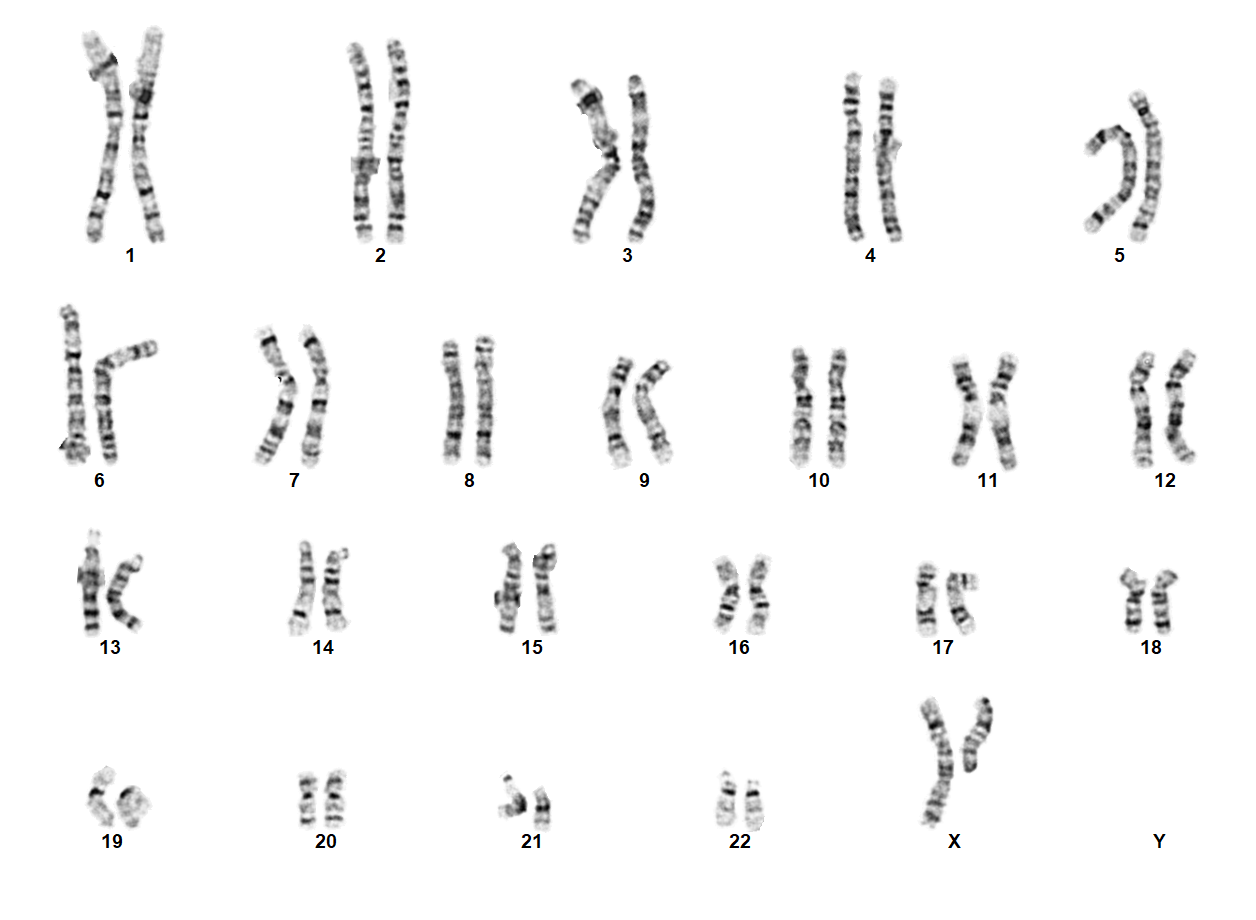

| + | [[File:46,X,psu idic(X)(q13.2).png|center|thumb|G-banded chromosome analysis of a PHA-stimulated peripheral blood specimen from a patient with variant Turner syndrome and a karyotype of 46,X,psu idic(X)(q13.2)/45,X; Courtesy of Wisconsin Diagnostics Laboratories]] | ||

| + | [[File:46,X,del(X)(p21.1).png|center|thumb|G-banded chromosome analysis of a PHA-stimulated peripheral blood specimen from a patient with variant Turner syndrome and a karyotype of 46,X,del(X)(p21.1)/45,X; Courtesy of Wisconsin Diagnostics Laboratories]] | ||

| + | [[File:46,X,del(X)(q21.3).png|center|thumb|G-banded chromosome analysis of a PHA-stimulated peripheral blood specimen from a patient with variant Turner syndrome and a karyotype of 46,X,del(X)(q21.3)/45,X; Courtesy of Wisconsin Diagnostics Laboratories]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In 45,X females, ovarian tissue is generally replaced with streak gonads, and most TS individuals are thus infertile. While spontaneous pregnancies have been reported in ~2-8% of TS females, it has been speculated that a normal cell line is present in the gonads of such individuals.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Pasquino|first=A. M.|last2=Passeri|first2=F.|last3=Pucarelli|first3=I.|last4=Segni|first4=M.|last5=Municchi|first5=G.|date=1997-06|title=Spontaneous pubertal development in Turner's syndrome. Italian Study Group for Turner's Syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9177387|journal=The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism|volume=82|issue=6|pages=1810–1813|doi=10.1210/jcem.82.6.3970|issn=0021-972X|pmid=9177387}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hovatta|first=O.|date=1999-04|title=Pregnancies in women with Turner's syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10344582|journal=Annals of Medicine|volume=31|issue=2|pages=106–110|issn=0785-3890|pmid=10344582}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hadnott|first=Tracy N.|last2=Gould|first2=Harley N.|last3=Gharib|first3=Ahmed M.|last4=Bondy|first4=Carolyn A.|date=2011-06|title=Outcomes of spontaneous and assisted pregnancies in Turner syndrome: the U.S. National Institutes of Health experience|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21496813|journal=Fertility and Sterility|volume=95|issue=7|pages=2251–2256|doi=10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.085|issn=1556-5653|pmc=3130000|pmid=21496813}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Birkebaek|first=N. H.|last2=Crüger|first2=D.|last3=Hansen|first3=J.|last4=Nielsen|first4=J.|last5=Bruun-Petersen|first5=G.|date=2002-01|title=Fertility and pregnancy outcome in Danish women with Turner syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11903353|journal=Clinical Genetics|volume=61|issue=1|pages=35–39|doi=10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.610107.x|issn=0009-9163|pmid=11903353}}</ref> In individuals with mosaic TS and Y chromosomal material, external genitalia may vary from normal male to ambiguous to female with TS characteristics. The Y chromosome, if present, may also be structurally abnormal. A patient with TS showing evidence of virilization is more likely to be mosaic for a Y-containing cell line, which increases the risk for gonadoblastoma.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Gravholt|first=Claus H.|last2=Andersen|first2=Niels H.|last3=Christin-Maitre|first3=Sophie|last4=Davis|first4=Shanlee M.|last5=Duijnhouwer|first5=Anthonie|last6=Gawlik|first6=Aneta|last7=Maciel-Guerra|first7=Andrea T.|last8=Gutmark-Little|first8=Iris|last9=Fleischer|first9=Kathrin|date=2024-06-05|title=Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38748847|journal=European Journal of Endocrinology|volume=190|issue=6|pages=G53–G151|doi=10.1093/ejendo/lvae050|issn=1479-683X|pmid=38748847}}</ref> Screening for Y chromosomal material, by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or a molecular method, is recommended in such cases. | ||

| + | |||

==Epidemiology/Prevalence== | ==Epidemiology/Prevalence== | ||

| − | + | TS and its variants occur in approximately 1 in 2000 to 1 in 2500 live-born females.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Cui|first=Xiaoxiao|last2=Cui|first2=Yazhou|last3=Shi|first3=Liang|last4=Luan|first4=Jing|last5=Zhou|first5=Xiaoyan|last6=Han|first6=Jinxiang|date=2018-11|title=A basic understanding of Turner syndrome: Incidence, complications, diagnosis, and treatment|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30560013|journal=Intractable & Rare Diseases Research|volume=7|issue=4|pages=223–228|doi=10.5582/irdr.2017.01056|issn=2186-3644|pmc=6290843|pmid=30560013}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Nielsen|first=J.|last2=Wohlert|first2=M.|date=1991-05|title=Chromosome abnormalities found among 34,910 newborn children: results from a 13-year incidence study in Arhus, Denmark|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2037286|journal=Human Genetics|volume=87|issue=1|pages=81–83|doi=10.1007/BF01213097|issn=0340-6717|pmid=2037286}}</ref> However, TS is among the most common chromosomal disorders, affecting 1–2% of conceptions, with approximately 99% of affected pregnancies resulting in pregnancy loss.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Urbach|first=Achia|last2=Benvenisty|first2=Nissim|date=2009|title=Studying early lethality of 45,XO (Turner's syndrome) embryos using human embryonic stem cells|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19137066|journal=PloS One|volume=4|issue=1|pages=e4175|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0004175|issn=1932-6203|pmc=2613558|pmid=19137066}}</ref> The true prevalence of TS is difficult to ascertain, as many individuals remain undiagnosed or are only diagnosed later in adulthood.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Gunther|first=Daniel F.|last2=Eugster|first2=Erica|last3=Zagar|first3=Anthony J.|last4=Bryant|first4=Constance G.|last5=Davenport|first5=Marsha L.|last6=Quigley|first6=Charmian A.|date=2004-09|title=Ascertainment bias in Turner syndrome: new insights from girls who were diagnosed incidentally in prenatal life|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15342833|journal=Pediatrics|volume=114|issue=3|pages=640–644|doi=10.1542/peds.2003-1122-L|issn=1098-4275|pmid=15342833}}</ref> | |

==Genetic Abnormalities: Germline== | ==Genetic Abnormalities: Germline== | ||

| − | |||

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 46: | Line 53: | ||

!Notes | !Notes | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |< | + | |''SHOX''||Whole or partial X chromosome loss encompassing gene||Haploinsufficiency||''De novo'', complete penetrance, complete expressivity |

| − | + | |The ''short stature homeobox'' (''SHOX'') gene belongs to the paired homeobox family and is located in the pseudoautosomal region 1 (PAR1) on the short arms of the X (Xp22.3) and Y (Yp11.3) chromosomes.<ref name=":3" /> It plays a crucial role in skeletal development, particularly in the growth plates of bones, where it regulates the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes, the cells responsible for cartilage formation. ''SHOX'' is vital for normal bone growth and stature, and pathogenic variants or deletions in this gene are associated with TS and other syndromes, including Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis, and idiopathic short stature.<ref name=":2" /> Both males and females typically have two copies of the ''SHOX'' gene, as it escapes X chromosome inactivation.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":4" /> | |

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |< | + | |''SRY'' |

| − | | | + | |Presence of Y chromosomal material |

| − | | | + | |N/A |

| − | | | + | |N/A |

| − | | | + | |The presence of Y chromosomal material, specifically the ''sex-determining region Y'' (''SRY)'' gene carries a risk of developing gonadoblastoma, with reported incidences ranging from 7% to 33%.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Gravholt|first=C. H.|last2=Fedder|first2=J.|last3=Naeraa|first3=R. W.|last4=Müller|first4=J.|date=2000-09|title=Occurrence of gonadoblastoma in females with Turner syndrome and Y chromosome material: a population study|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10999808|journal=The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism|volume=85|issue=9|pages=3199–3202|doi=10.1210/jcem.85.9.6800|issn=0021-972X|pmid=10999808}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Mazzanti|first=Laura|last2=Cicognani|first2=Alessandro|last3=Baldazzi|first3=Lilia|last4=Bergamaschi|first4=Rosalba|last5=Scarano|first5=Emanuela|last6=Strocchi|first6=Simona|last7=Nicoletti|first7=Annalisa|last8=Mencarelli|first8=Francesca|last9=Pittalis|first9=Mariacarla|date=2005-06-01|title=Gonadoblastoma in Turner syndrome and Y-chromosome-derived material|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15880570|journal=American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A|volume=135|issue=2|pages=150–154|doi=10.1002/ajmg.a.30569|issn=1552-4825|pmid=15880570}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kwon|first=Ahreum|last2=Hyun|first2=Sei Eun|last3=Jung|first3=Mo Kyung|last4=Chae|first4=Hyun Wook|last5=Lee|first5=Woo Jung|last6=Kim|first6=Tae Hyuk|last7=Kim|first7=Duk Hee|last8=Kim|first8=Ho-Seong|date=2017-06|title=Risk of Gonadoblastoma Development in Patients with Turner Syndrome with Cryptic Y Chromosome Material|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28349385|journal=Hormones & Cancer|volume=8|issue=3|pages=166–173|doi=10.1007/s12672-017-0291-8|issn=1868-8500|pmc=PMC10355848|pmid=28349385}}</ref> The risk is higher with the presence of the ''testis-specific protein Y-linked 1'' (''TSPY1)'' gene, which promotes germ cell proliferation, increasing the risk for tumor development.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bianco|first=Bianca|last2=Lipay|first2=Mônica|last3=Guedes|first3=Alexis|last4=Oliveira|first4=Kelly|last5=Verreschi|first5=Ieda T. N.|date=2009-03|title=SRY gene increases the risk of developing gonadoblastoma and/or nontumoral gonadal lesions in Turner syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19188812|journal=International Journal of Gynecological Pathology: Official Journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists|volume=28|issue=2|pages=197–202|doi=10.1097/PGP.0b013e318186a825|issn=1538-7151|pmid=19188812}}</ref> TSPY1 expression can synergize with other tumor-promoting factors, such as octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4), KIT proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase (c-KIT), and KIT ligand (KITLG), maintaining germ cells in a proliferative, undifferentiated state.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Li|first=Yunmin|last2=Tabatabai|first2=Z. Laura|last3=Lee|first3=Tin-Lap|last4=Hatakeyama|first4=Shingo|last5=Ohyama|first5=Chikara|last6=Chan|first6=Wai-Yee|last7=Looijenga|first7=Leendert H. J.|last8=Lau|first8=Yun-Fai Chris|date=2007-10|title=The Y-encoded TSPY protein: a significant marker potentially plays a role in the pathogenesis of testicular germ cell tumors|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17521702|journal=Human Pathology|volume=38|issue=10|pages=1470–1481|doi=10.1016/j.humpath.2007.03.011|issn=0046-8177|pmc=2744854|pmid=17521702}}</ref> |

| − | |- | ||

| − | | | ||

| − | | | ||

| − | | | ||

| − | | | ||

| − | | | ||

|} | |} | ||

==Genetic Abnormalities: Somatic== | ==Genetic Abnormalities: Somatic== | ||

| − | + | N/A | |

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

!Notes | !Notes | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |N/A||N/A||N/A||N/A |

| − | + | |N/A | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

==Genes and Main Pathways Involved== | ==Genes and Main Pathways Involved== | ||

| − | + | N/A | |

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

!Gene; Genetic Alteration!!Pathway!!Pathophysiologic Outcome | !Gene; Genetic Alteration!!Pathway!!Pathophysiologic Outcome | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |N/A |

| − | | | + | |N/A |

| − | | | + | |N/A |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

==Genetic Diagnostic Testing Methods== | ==Genetic Diagnostic Testing Methods== | ||

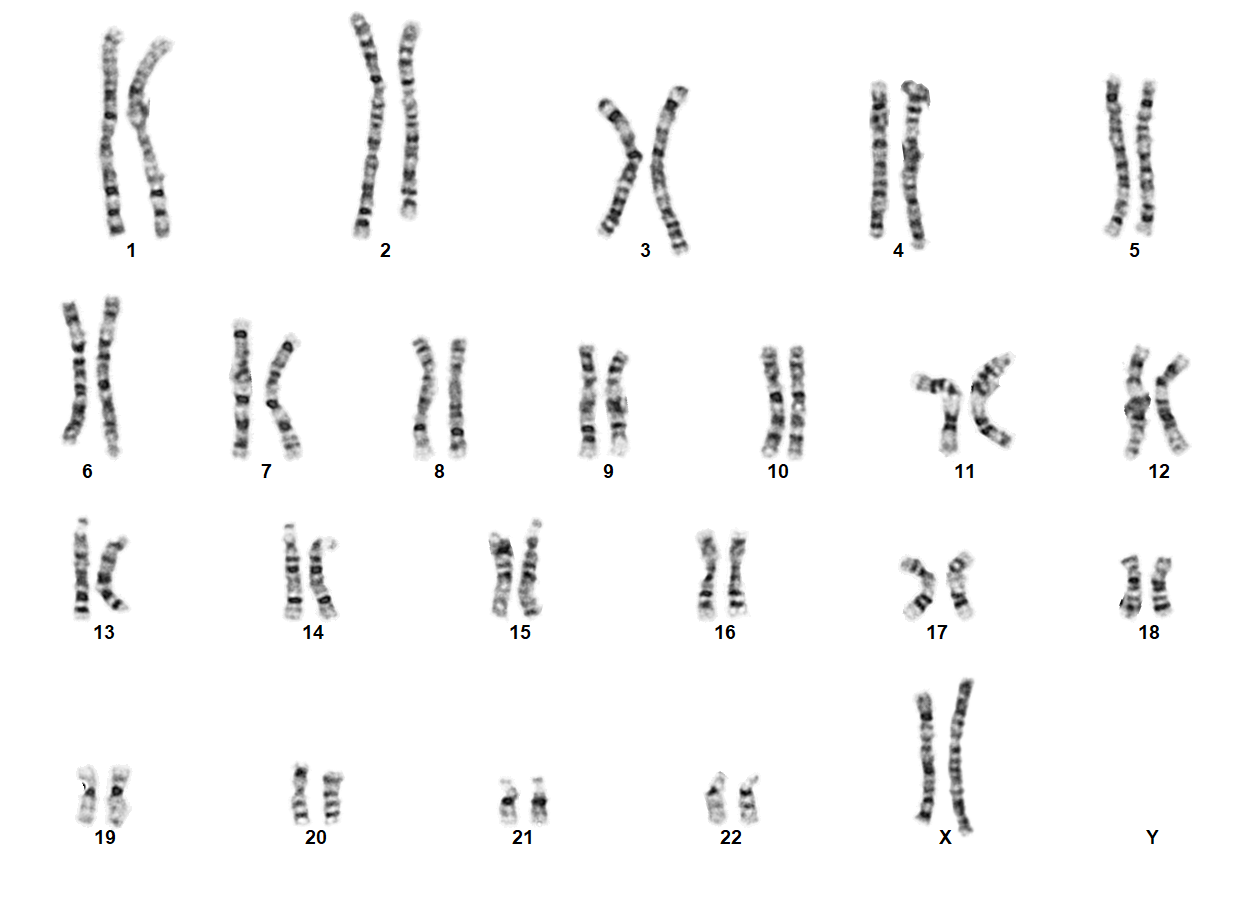

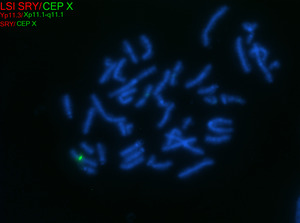

| − | + | TS can be diagnosed prenatally through chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis, followed by G-banded chromosome analysis or karyotyping. Postnatal confirmation requires chromosome analysis of a phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated peripheral blood (PB) specimen. In cases of mosaicism, the karyotype may appear normal, so additional diagnostic methods may be necessary. If TS is strongly suspected, a FISH study using an X chromosome centromere probe may be performed alongside karyotyping. Furthermore, if clinical suspicion remains high despite normal results from chromosome analysis and FISH, chromosome analysis of a skin fibroblast culture may be indicated. | |

| + | [[File:FISH for turner syndrome.tif|center|thumb|Metaphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis for the X chromosome centromere (green) in an individual with non-mosaic Turner syndrome and a 45,X karyotype.]] | ||

| + | [[File:Interphase FISH for turner syndrome.tif|center|thumb|Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis for the X chromosome centromere (green) in an individual with non-mosaic Turner syndrome and a 45,X karyotype.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

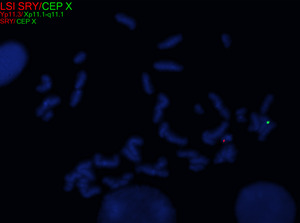

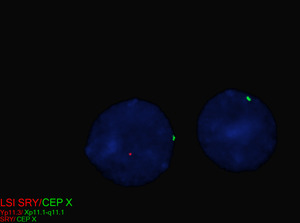

| + | In patients with TS who exhibit signs of virilization, the presence of Y chromosomal material is a significant concern, as it increases the risk for the development of gonadoblastoma, a type of germ cell tumor.<ref name=":1" /> To detect Y chromosomal material, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a sensitive and specific molecular method used for screening. PCR involves amplifying DNA sequences specific to the Y chromosome, such as ''SRY'' (sex-determining region Y), ''TSPY1'' (testis-specific protein Y-encoded), or other Y-specific markers.<ref name=":5" /> This technique can identify even low levels of mosaicism, which might not be detectable by conventional karyotyping or FISH. FISH can also be used to screen for SRY. When Y chromosomal material is confirmed, preventive measures, such as gonadectomy, are typically recommended to reduce the risk of malignancy.<ref name=":1" /> PCR is particularly valuable in cases where clinical findings and standard cytogenetic testing are inconclusive but there is strong clinical suspicion of Y chromosomal mosaicism. This molecular approach complements cytogenetic methods, providing a comprehensive evaluation for patients with TS and virilization. | ||

| + | [[File:SRY in 45,X-46,XY.tif|center|thumb|Metaphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis for SRY (red) and the X chromosome centromere (green) in an individual with Turner syndrome and a 45,X/46,XY karyotype.]] | ||

| + | [[File:Interphase SRY.tif|center|thumb|Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis for SRY (red) and the X chromosome centromere (green) in an individual with Turner syndrome and a 45,X/46,XY karyotype.]] | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

==Additional Information== | ==Additional Information== | ||

Put your text here | Put your text here | ||

| Line 113: | Line 97: | ||

Put a link here or anywhere appropriate in this page <span style="color:#0070C0">(''Instructions: Highlight the text to which you want to add a link in this section or elsewhere, select the "Link" icon at the top of the wiki page, and search the name of the internal page to which you want to link this text, or enter an external internet address by including the "<nowiki>http://www</nowiki>." portion.'')</span> | Put a link here or anywhere appropriate in this page <span style="color:#0070C0">(''Instructions: Highlight the text to which you want to add a link in this section or elsewhere, select the "Link" icon at the top of the wiki page, and search the name of the internal page to which you want to link this text, or enter an external internet address by including the "<nowiki>http://www</nowiki>." portion.'')</span> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | <references /> | |

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<nowiki>*</nowiki>Primary authors will typically be those that initially create and complete the content of a page. If a subsequent user modifies the content and feels the effort put forth is of high enough significance to warrant listing in the authorship section, please contact the [[Leadership|''<u>Associate Editor</u>'']] or other CCGA representative. When pages have a major update, the new author will be acknowledged at the beginning of the page, and those who contributed previously will be acknowledged below as a prior author. | <nowiki>*</nowiki>Primary authors will typically be those that initially create and complete the content of a page. If a subsequent user modifies the content and feels the effort put forth is of high enough significance to warrant listing in the authorship section, please contact the [[Leadership|''<u>Associate Editor</u>'']] or other CCGA representative. When pages have a major update, the new author will be acknowledged at the beginning of the page, and those who contributed previously will be acknowledged below as a prior author. | ||

Prior Author(s): | Prior Author(s): | ||

| − | [[Category:GTS5]][[Category:DISEASE]] | + | [[Category:GTS5]] |

| + | [[Category:DISEASE]] | ||

| Line 129: | Line 114: | ||

==Primary Author(s)*== | ==Primary Author(s)*== | ||

Kathleen Bone, PhD, Medical College of Wisconsin | Kathleen Bone, PhD, Medical College of Wisconsin | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 174: | Line 127: | ||

|Haploinsufficiency | |Haploinsufficiency | ||

|''De novo'', complete penetrance, complete expressivity | |''De novo'', complete penetrance, complete expressivity | ||

| − | |The ''short stature homeobox'' (''SHOX'') gene belongs to the paired homeobox family and is located in the pseudoautosomal region 1 (PAR1) on the short arms of the X (Xp22.3) and Y (Yp11.3) chromosomes.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Rao|first=E.|last2=Weiss|first2=B.|last3=Fukami|first3=M.|last4=Rump|first4=A.|last5=Niesler|first5=B.|last6=Mertz|first6=A.|last7=Muroya|first7=K.|last8=Binder|first8=G.|last9=Kirsch|first9=S.|date=1997-05|title=Pseudoautosomal deletions encompassing a novel homeobox gene cause growth failure in idiopathic short stature and Turner syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9140395|journal=Nature Genetics|volume=16|issue=1|pages=54–63|doi=10.1038/ng0597-54|issn=1061-4036|pmid=9140395}}</ref> It plays a crucial role in skeletal development, particularly in the growth plates of bones, where it regulates the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes, the cells responsible for cartilage formation. ''SHOX'' is vital for normal bone growth and stature, and pathogenic variants or deletions in this gene are associated with TS and other syndromes, including Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis, and idiopathic short stature.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last=Binder|first=Gerhard|date=2011-02|title=Short stature due to SHOX deficiency: genotype, phenotype, and therapy|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21325865|journal=Hormone Research in Paediatrics|volume=75|issue=2|pages=81–89|doi=10.1159/000324105|issn=1663-2826|pmid=21325865}}</ref> Both males and females typically have two copies of the ''SHOX'' gene, as it escapes X chromosome inactivation.<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Berletch|first=Joel B.|last2=Yang|first2=Fan|last3=Xu|first3=Jun|last4=Carrel|first4=Laura|last5=Disteche|first5=Christine M.|date=2011-08|title=Genes that escape from X inactivation|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21614513|journal=Human Genetics|volume=130|issue=2|pages=237–245|doi=10.1007/s00439-011-1011-z|issn=1432-1203|pmc=3136209|pmid=21614513}}</ref> | + | |The ''short stature homeobox'' (''SHOX'') gene belongs to the paired homeobox family and is located in the pseudoautosomal region 1 (PAR1) on the short arms of the X (Xp22.3) and Y (Yp11.3) chromosomes.<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal|last=Rao|first=E.|last2=Weiss|first2=B.|last3=Fukami|first3=M.|last4=Rump|first4=A.|last5=Niesler|first5=B.|last6=Mertz|first6=A.|last7=Muroya|first7=K.|last8=Binder|first8=G.|last9=Kirsch|first9=S.|date=1997-05|title=Pseudoautosomal deletions encompassing a novel homeobox gene cause growth failure in idiopathic short stature and Turner syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9140395|journal=Nature Genetics|volume=16|issue=1|pages=54–63|doi=10.1038/ng0597-54|issn=1061-4036|pmid=9140395}}</ref> It plays a crucial role in skeletal development, particularly in the growth plates of bones, where it regulates the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes, the cells responsible for cartilage formation. ''SHOX'' is vital for normal bone growth and stature, and pathogenic variants or deletions in this gene are associated with TS and other syndromes, including Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis, and idiopathic short stature.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last=Binder|first=Gerhard|date=2011-02|title=Short stature due to SHOX deficiency: genotype, phenotype, and therapy|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21325865|journal=Hormone Research in Paediatrics|volume=75|issue=2|pages=81–89|doi=10.1159/000324105|issn=1663-2826|pmid=21325865}}</ref> Both males and females typically have two copies of the ''SHOX'' gene, as it escapes X chromosome inactivation.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last=Berletch|first=Joel B.|last2=Yang|first2=Fan|last3=Xu|first3=Jun|last4=Carrel|first4=Laura|last5=Disteche|first5=Christine M.|date=2011-08|title=Genes that escape from X inactivation|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21614513|journal=Human Genetics|volume=130|issue=2|pages=237–245|doi=10.1007/s00439-011-1011-z|issn=1432-1203|pmc=3136209|pmid=21614513}}</ref> |

|} | |} | ||

==Genetic Abnormalities: Somatic== | ==Genetic Abnormalities: Somatic== | ||

| Line 215: | Line 168: | ||

If TS is strongly suspected, a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) study using an X chromosome centromere probe may be performed alongside karyotyping. Furthermore, if clinical suspicion remains high despite normal results from chromosome analysis and FISH, a chromosome analysis of a skin fibroblast culture may be indicated. | If TS is strongly suspected, a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) study using an X chromosome centromere probe may be performed alongside karyotyping. Furthermore, if clinical suspicion remains high despite normal results from chromosome analysis and FISH, a chromosome analysis of a skin fibroblast culture may be indicated. | ||

| − | In patients with TS who exhibit signs of virilization, the presence of Y chromosomal material is a significant concern, as it increases the risk for the development of gonadoblastoma, a type of germ cell tumor.<ref name=":1" /> To detect Y chromosomal material, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a sensitive and specific molecular method used for screening. PCR involves amplifying DNA sequences specific to the Y chromosome, such as SRY (sex-determining region Y), TSPY (testis-specific protein Y-encoded), or other Y-specific markers.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Mendes|first=J. R.|last2=Strufaldi|first2=M. W.|last3=Delcelo|first3=R.|last4=Moisés|first4=R. C.|last5=Vieira|first5=J. G.|last6=Kasamatsu|first6=T. S.|last7=Galera|first7=M. F.|last8=Andrade|first8=J. A.|last9=Verreschi|first9=I. T.|date=1999-01|title=Y-chromosome identification by PCR and gonadal histopathology in Turner's syndrome without overt Y-mosaicism|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10341852|journal=Clinical Endocrinology|volume=50|issue=1|pages=19–26|doi=10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00607.x|issn=0300-0664|pmid=10341852}}</ref> This technique can identify even low levels of mosaicism, which might not be detectable by conventional karyotyping or FISH. When Y chromosomal material is confirmed, preventive measures, such as gonadectomy, are typically recommended to reduce the risk of malignancy.<ref name=":1" /> PCR is particularly valuable in cases where clinical findings and standard cytogenetic testing are inconclusive but there is strong clinical suspicion of Y chromosomal mosaicism. This molecular approach complements cytogenetic methods, providing a comprehensive evaluation for patients with TS and virilization. | + | In patients with TS who exhibit signs of virilization, the presence of Y chromosomal material is a significant concern, as it increases the risk for the development of gonadoblastoma, a type of germ cell tumor.<ref name=":1" /> To detect Y chromosomal material, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a sensitive and specific molecular method used for screening. PCR involves amplifying DNA sequences specific to the Y chromosome, such as SRY (sex-determining region Y), TSPY (testis-specific protein Y-encoded), or other Y-specific markers.<ref name=":5">{{Cite journal|last=Mendes|first=J. R.|last2=Strufaldi|first2=M. W.|last3=Delcelo|first3=R.|last4=Moisés|first4=R. C.|last5=Vieira|first5=J. G.|last6=Kasamatsu|first6=T. S.|last7=Galera|first7=M. F.|last8=Andrade|first8=J. A.|last9=Verreschi|first9=I. T.|date=1999-01|title=Y-chromosome identification by PCR and gonadal histopathology in Turner's syndrome without overt Y-mosaicism|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10341852|journal=Clinical Endocrinology|volume=50|issue=1|pages=19–26|doi=10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00607.x|issn=0300-0664|pmid=10341852}}</ref> This technique can identify even low levels of mosaicism, which might not be detectable by conventional karyotyping or FISH. When Y chromosomal material is confirmed, preventive measures, such as gonadectomy, are typically recommended to reduce the risk of malignancy.<ref name=":1" /> PCR is particularly valuable in cases where clinical findings and standard cytogenetic testing are inconclusive but there is strong clinical suspicion of Y chromosomal mosaicism. This molecular approach complements cytogenetic methods, providing a comprehensive evaluation for patients with TS and virilization. |

==Additional Information== | ==Additional Information== | ||

Revision as of 12:53, 10 March 2025

| This page is under construction |

(General Instructions – The focus of these pages is the clinically significant genetic alterations in each disease type. This is based on up-to-date knowledge from multiple resources such as PubMed and the WHO classification books. The CCGA is meant to be a supplemental resource to the WHO classification books; the CCGA captures in a continually updated wiki-style manner the current genetics/genomics knowledge of each disease, which evolves more rapidly than books can be revised and published. If the same disease is described in multiple WHO classification books, the genetics-related information for that disease will be consolidated into a single main page that has this template (other pages would only contain a link to this main page). Use HUGO-approved gene names and symbols (italicized when appropriate), HGVS-based nomenclature for variants, as well as generic names of drugs and testing platforms or assays if applicable. Please complete tables whenever possible and do not delete them (add N/A if not applicable in the table and delete the examples); to add (or move) a row or column in a table, click nearby within the table and select the > symbol that appears. Please do not delete or alter the section headings. The use of bullet points alongside short blocks of text rather than only large paragraphs is encouraged. Additional instructions below in italicized blue text should not be included in the final page content. Please also see Author_Instructions and FAQs as well as contact your Associate Editor or Technical Support.)

Primary Author(s)*

Kathleen M. Bone, PhD, Medical College of Wisconsin

WHO Classification of Disease

| Structure | Disease |

|---|---|

| Book | Genetic Tumor Syndromes (5th ed.) |

| Category | DNA repair and genomic instability |

| Family | Chromosomal and non-dysjunction (aneuploidy) syndromes |

| Type | N/A |

| Subtype(s) | Turner Syndrome |

Related Terminology

| Acceptable | 45,X syndrome; Ullrich-Turner syndrome |

| Not Recommended | 45,XO syndrome |

Definition/Description of Disease

Turner Syndrome (TS) is a rare chromosomal disorder resulting from complete or partial loss of the second sex chromosome. The most common clinical manifestations include short stature, ovarian failure, primary or secondary amenorrhea associated with hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, congenital lymphedema of the hands and feet, Madelung deformity of the forearm and wrist, webbed neck, cardiac anomalies such as coarctation of the aorta, bicuspid aortic valves, mitral valve prolapse, hypertension, ischemic heart disease and arteriosclerosis, impaired glucose tolerance, thyroid disease and hearing loss.[1][2][3][4][5][6] Despite considerable phenotypic variability, short stature and gonadal dysgenesis are the most consistent findings. While individuals with TS may experience impairments in nonverbal developmental skills, they generally have normal intellectual ability.[7] TS should be suspected prenatally when a prenatal ultrasound reveals fetal hydrops, cystic hygroma, or cardiac defects. Approximately 50% of TS patients have monosomy X (45,X), while the remaining 50% exhibit various structural abnormalities of the X chromosome or mosaicism with a normal female or normal male cell line.

In 45,X females, ovarian tissue is generally replaced with streak gonads, and most TS individuals are thus infertile. While spontaneous pregnancies have been reported in ~2-8% of TS females, it has been speculated that a normal cell line is present in the gonads of such individuals.[8][9][10][11] In individuals with mosaic TS and Y chromosomal material, external genitalia may vary from normal male to ambiguous to female with TS characteristics. The Y chromosome, if present, may also be structurally abnormal. A patient with TS showing evidence of virilization is more likely to be mosaic for a Y-containing cell line, which increases the risk for gonadoblastoma.[1][12] Screening for Y chromosomal material, by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or a molecular method, is recommended in such cases.

Epidemiology/Prevalence

TS and its variants occur in approximately 1 in 2000 to 1 in 2500 live-born females.[13][14] However, TS is among the most common chromosomal disorders, affecting 1–2% of conceptions, with approximately 99% of affected pregnancies resulting in pregnancy loss.[15] The true prevalence of TS is difficult to ascertain, as many individuals remain undiagnosed or are only diagnosed later in adulthood.[16]

Genetic Abnormalities: Germline

| Gene | Genetic Variant or Variant Type | Molecular Pathogenesis | Inheritance, Penetrance, Expressivity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHOX | Whole or partial X chromosome loss encompassing gene | Haploinsufficiency | De novo, complete penetrance, complete expressivity | The short stature homeobox (SHOX) gene belongs to the paired homeobox family and is located in the pseudoautosomal region 1 (PAR1) on the short arms of the X (Xp22.3) and Y (Yp11.3) chromosomes.[17] It plays a crucial role in skeletal development, particularly in the growth plates of bones, where it regulates the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes, the cells responsible for cartilage formation. SHOX is vital for normal bone growth and stature, and pathogenic variants or deletions in this gene are associated with TS and other syndromes, including Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis, and idiopathic short stature.[18] Both males and females typically have two copies of the SHOX gene, as it escapes X chromosome inactivation.[18][19] |

| SRY | Presence of Y chromosomal material | N/A | N/A | The presence of Y chromosomal material, specifically the sex-determining region Y (SRY) gene carries a risk of developing gonadoblastoma, with reported incidences ranging from 7% to 33%.[20][21][22] The risk is higher with the presence of the testis-specific protein Y-linked 1 (TSPY1) gene, which promotes germ cell proliferation, increasing the risk for tumor development.[23] TSPY1 expression can synergize with other tumor-promoting factors, such as octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4), KIT proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase (c-KIT), and KIT ligand (KITLG), maintaining germ cells in a proliferative, undifferentiated state.[24] |

Genetic Abnormalities: Somatic

N/A

| Gene | Genetic Variant or Variant Type | Molecular Pathogenesis | Inheritance, Penetrance, Expressivity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Genes and Main Pathways Involved

N/A

| Gene; Genetic Alteration | Pathway | Pathophysiologic Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

Genetic Diagnostic Testing Methods

TS can be diagnosed prenatally through chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis, followed by G-banded chromosome analysis or karyotyping. Postnatal confirmation requires chromosome analysis of a phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated peripheral blood (PB) specimen. In cases of mosaicism, the karyotype may appear normal, so additional diagnostic methods may be necessary. If TS is strongly suspected, a FISH study using an X chromosome centromere probe may be performed alongside karyotyping. Furthermore, if clinical suspicion remains high despite normal results from chromosome analysis and FISH, chromosome analysis of a skin fibroblast culture may be indicated.

In patients with TS who exhibit signs of virilization, the presence of Y chromosomal material is a significant concern, as it increases the risk for the development of gonadoblastoma, a type of germ cell tumor.[12] To detect Y chromosomal material, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a sensitive and specific molecular method used for screening. PCR involves amplifying DNA sequences specific to the Y chromosome, such as SRY (sex-determining region Y), TSPY1 (testis-specific protein Y-encoded), or other Y-specific markers.[25] This technique can identify even low levels of mosaicism, which might not be detectable by conventional karyotyping or FISH. FISH can also be used to screen for SRY. When Y chromosomal material is confirmed, preventive measures, such as gonadectomy, are typically recommended to reduce the risk of malignancy.[12] PCR is particularly valuable in cases where clinical findings and standard cytogenetic testing are inconclusive but there is strong clinical suspicion of Y chromosomal mosaicism. This molecular approach complements cytogenetic methods, providing a comprehensive evaluation for patients with TS and virilization.

Additional Information

Put your text here

Links

Put a link here or anywhere appropriate in this page (Instructions: Highlight the text to which you want to add a link in this section or elsewhere, select the "Link" icon at the top of the wiki page, and search the name of the internal page to which you want to link this text, or enter an external internet address by including the "http://www." portion.)

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Gravholt, Claus H. (2005-11). "Clinical practice in Turner syndrome". Nature Clinical Practice. Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1 (1): 41–52. doi:10.1038/ncpendmet0024. ISSN 1745-8366. PMID 16929365. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Bondy, Carolyn A.; et al. (2006-07). "Investigation of cardiac status and bone mineral density in Turner syndrome". Growth hormone & IGF research: official journal of the Growth Hormone Research Society and the International IGF Research Society. 16 Suppl A: S103–108. doi:10.1016/j.ghir.2006.03.008. ISSN 1096-6374. PMID 16624607. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Dhooge, Ingeborg J. M.; et al. (2005-03). "Otologic disease in turner syndrome". Otology & Neurotology: Official Publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 26 (2): 145–150. doi:10.1097/00129492-200503000-00003. ISSN 1531-7129. PMID 15793396. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Güngör, N.; et al. (2000-10). "High frequency hearing loss in Ullrich-Turner syndrome". European Journal of Pediatrics. 159 (10): 740–744. doi:10.1007/pl00008338. ISSN 0340-6199. PMID 11039128. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Zinn, A. R.; et al. (1998-12). "Evidence for a Turner syndrome locus or loci at Xp11.2-p22.1". American Journal of Human Genetics. 63 (6): 1757–1766. doi:10.1086/302152. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1377648. PMID 9837829. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Sävendahl, L.; et al. (2000-10). "Delayed diagnoses of Turner's syndrome: proposed guidelines for change". The Journal of Pediatrics. 137 (4): 455–459. doi:10.1067/mpd.2000.107390. ISSN 0022-3476. PMID 11035820. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Kesler, Shelli R. (2007-07). "Turner syndrome". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 16 (3): 709–722. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2007.02.004. ISSN 1056-4993. PMC 2023872. PMID 17562588. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Pasquino, A. M.; et al. (1997-06). "Spontaneous pubertal development in Turner's syndrome. Italian Study Group for Turner's Syndrome". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 82 (6): 1810–1813. doi:10.1210/jcem.82.6.3970. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 9177387. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Hovatta, O. (1999-04). "Pregnancies in women with Turner's syndrome". Annals of Medicine. 31 (2): 106–110. ISSN 0785-3890. PMID 10344582. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Hadnott, Tracy N.; et al. (2011-06). "Outcomes of spontaneous and assisted pregnancies in Turner syndrome: the U.S. National Institutes of Health experience". Fertility and Sterility. 95 (7): 2251–2256. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.085. ISSN 1556-5653. PMC 3130000. PMID 21496813. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Birkebaek, N. H.; et al. (2002-01). "Fertility and pregnancy outcome in Danish women with Turner syndrome". Clinical Genetics. 61 (1): 35–39. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.610107.x. ISSN 0009-9163. PMID 11903353. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 Gravholt, Claus H.; et al. (2024-06-05). "Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome". European Journal of Endocrinology. 190 (6): G53–G151. doi:10.1093/ejendo/lvae050. ISSN 1479-683X. PMID 38748847 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Cui, Xiaoxiao; et al. (2018-11). "A basic understanding of Turner syndrome: Incidence, complications, diagnosis, and treatment". Intractable & Rare Diseases Research. 7 (4): 223–228. doi:10.5582/irdr.2017.01056. ISSN 2186-3644. PMC 6290843. PMID 30560013. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Nielsen, J.; et al. (1991-05). "Chromosome abnormalities found among 34,910 newborn children: results from a 13-year incidence study in Arhus, Denmark". Human Genetics. 87 (1): 81–83. doi:10.1007/BF01213097. ISSN 0340-6717. PMID 2037286. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Urbach, Achia; et al. (2009). "Studying early lethality of 45,XO (Turner's syndrome) embryos using human embryonic stem cells". PloS One. 4 (1): e4175. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004175. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2613558. PMID 19137066.

- ↑ Gunther, Daniel F.; et al. (2004-09). "Ascertainment bias in Turner syndrome: new insights from girls who were diagnosed incidentally in prenatal life". Pediatrics. 114 (3): 640–644. doi:10.1542/peds.2003-1122-L. ISSN 1098-4275. PMID 15342833. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:3 - ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:2 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:4 - ↑ Gravholt, C. H.; et al. (2000-09). "Occurrence of gonadoblastoma in females with Turner syndrome and Y chromosome material: a population study". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 85 (9): 3199–3202. doi:10.1210/jcem.85.9.6800. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 10999808. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Mazzanti, Laura; et al. (2005-06-01). "Gonadoblastoma in Turner syndrome and Y-chromosome-derived material". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 135 (2): 150–154. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.30569. ISSN 1552-4825. PMID 15880570.

- ↑ Kwon, Ahreum; et al. (2017-06). "Risk of Gonadoblastoma Development in Patients with Turner Syndrome with Cryptic Y Chromosome Material". Hormones & Cancer. 8 (3): 166–173. doi:10.1007/s12672-017-0291-8. ISSN 1868-8500. PMC PMC10355848 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 28349385. Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ↑ Bianco, Bianca; et al. (2009-03). "SRY gene increases the risk of developing gonadoblastoma and/or nontumoral gonadal lesions in Turner syndrome". International Journal of Gynecological Pathology: Official Journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists. 28 (2): 197–202. doi:10.1097/PGP.0b013e318186a825. ISSN 1538-7151. PMID 19188812. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Li, Yunmin; et al. (2007-10). "The Y-encoded TSPY protein: a significant marker potentially plays a role in the pathogenesis of testicular germ cell tumors". Human Pathology. 38 (10): 1470–1481. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2007.03.011. ISSN 0046-8177. PMC 2744854. PMID 17521702. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:5

Notes

*Primary authors will typically be those that initially create and complete the content of a page. If a subsequent user modifies the content and feels the effort put forth is of high enough significance to warrant listing in the authorship section, please contact the Associate Editor or other CCGA representative. When pages have a major update, the new author will be acknowledged at the beginning of the page, and those who contributed previously will be acknowledged below as a prior author.

Prior Author(s):

THIS IS WEHRE THE OLD TEMPLATE BEGINS

| This page is under construction |

(General Instructions – The focus of these pages is the clinically significant genetic alterations in each disease type, which is based on current knowledge within the WHO classification books and using resources such as PubMed for the latest information. If the same disease is described in multiple WHO classification books, the genetics-related information for that disease will be consolidated into a single main page that has this template (other pages would only contain a link to this main page). Use HUGO-approved gene names and symbols (italicized when appropriate), HGVS-based nomenclature for variants, as well as generic names of drugs and testing platforms or assays if applicable. Please complete tables whenever possible and do not delete them (add N/A if not applicable in the table and delete the examples); to add (or move) a row or column in a table, click nearby within the table and select the > symbol that appears. Please do not delete or alter the section headings. The use of bullet points alongside short blocks of text rather than only large paragraphs is encouraged. Additional instructions below in italicized blue text should not be included in the final page content. Please also see Author_Instructions and FAQs as well as contact your Associate Editor or Technical Support)

Primary Author(s)*

Kathleen Bone, PhD, Medical College of Wisconsin

| Gene | Genetic Variant or Variant Type | Molecular Pathogenesis | Inheritance, Penetrance, Expressivity | Notes |

| SHOX | Whole or partial X chromosome loss encompassing gene | Haploinsufficiency | De novo, complete penetrance, complete expressivity | The short stature homeobox (SHOX) gene belongs to the paired homeobox family and is located in the pseudoautosomal region 1 (PAR1) on the short arms of the X (Xp22.3) and Y (Yp11.3) chromosomes.[1] It plays a crucial role in skeletal development, particularly in the growth plates of bones, where it regulates the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes, the cells responsible for cartilage formation. SHOX is vital for normal bone growth and stature, and pathogenic variants or deletions in this gene are associated with TS and other syndromes, including Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis, and idiopathic short stature.[2] Both males and females typically have two copies of the SHOX gene, as it escapes X chromosome inactivation.[2][3] |

Genetic Abnormalities: Somatic

N/A

| Gene | Genetic Variant or Variant Type | Molecular Pathogenesis | Inheritance, Penetrance, Expressivity | Notes |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Genes and Main Pathways Involved

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: Can include references in the table. Do not delete table.)

| Gene; Genetic Alteration | Pathway | Pathophysiologic Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE: BRAF and MAP2K1; Activating mutations | EXAMPLE: MAPK signaling | EXAMPLE: Increased cell growth and proliferation |

| EXAMPLE: CDKN2A; Inactivating mutations | EXAMPLE: Cell cycle regulation | EXAMPLE: Unregulated cell division |

| EXAMPLE: KMT2C and ARID1A; Inactivating mutations | EXAMPLE: Histone modification, chromatin remodeling | EXAMPLE: Abnormal gene expression program |

Genetic Diagnostic Testing Methods

TS can be diagnosed prenatally through chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis, followed by G-banded chromosome analysis or karyotyping. Postnatal confirmation requires chromosome analysis of a phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated peripheral blood (PB) specimen. In cases of mosaicism, the karyotype may appear normal, so additional diagnostic methods may be necessary.

If TS is strongly suspected, a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) study using an X chromosome centromere probe may be performed alongside karyotyping. Furthermore, if clinical suspicion remains high despite normal results from chromosome analysis and FISH, a chromosome analysis of a skin fibroblast culture may be indicated.

In patients with TS who exhibit signs of virilization, the presence of Y chromosomal material is a significant concern, as it increases the risk for the development of gonadoblastoma, a type of germ cell tumor.[4] To detect Y chromosomal material, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a sensitive and specific molecular method used for screening. PCR involves amplifying DNA sequences specific to the Y chromosome, such as SRY (sex-determining region Y), TSPY (testis-specific protein Y-encoded), or other Y-specific markers.[5] This technique can identify even low levels of mosaicism, which might not be detectable by conventional karyotyping or FISH. When Y chromosomal material is confirmed, preventive measures, such as gonadectomy, are typically recommended to reduce the risk of malignancy.[4] PCR is particularly valuable in cases where clinical findings and standard cytogenetic testing are inconclusive but there is strong clinical suspicion of Y chromosomal mosaicism. This molecular approach complements cytogenetic methods, providing a comprehensive evaluation for patients with TS and virilization.

Additional Information

Put your text here

Links

Put a link here or anywhere appropriate in this page (Instructions: Highlight the text to which you want to add a link in this section or elsewhere, select the "Link" icon at the top of the page, and search the name of the internal page to which you want to link this text, or enter an external internet address by including the "http://www." portion.)

References

- ↑ Rao, E.; et al. (1997-05). "Pseudoautosomal deletions encompassing a novel homeobox gene cause growth failure in idiopathic short stature and Turner syndrome". Nature Genetics. 16 (1): 54–63. doi:10.1038/ng0597-54. ISSN 1061-4036. PMID 9140395. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Binder, Gerhard (2011-02). "Short stature due to SHOX deficiency: genotype, phenotype, and therapy". Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 75 (2): 81–89. doi:10.1159/000324105. ISSN 1663-2826. PMID 21325865. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Berletch, Joel B.; et al. (2011-08). "Genes that escape from X inactivation". Human Genetics. 130 (2): 237–245. doi:10.1007/s00439-011-1011-z. ISSN 1432-1203. PMC 3136209. PMID 21614513. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:1 - ↑ Mendes, J. R.; et al. (1999-01). "Y-chromosome identification by PCR and gonadal histopathology in Turner's syndrome without overt Y-mosaicism". Clinical Endocrinology. 50 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00607.x. ISSN 0300-0664. PMID 10341852. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

(use the "Cite" icon at the top of the page) (Instructions: Add each reference into the text above by clicking where you want to insert the reference, selecting the “Cite” icon at the top of the page, and using the “Automatic” tab option to search by PMID to select the reference to insert. If a PMID is not available, such as for a book, please use the “Cite” icon, select “Manual” and then “Basic Form”, and include the entire reference. To insert the same reference again later in the page, select the “Cite” icon and “Re-use” to find the reference; DO NOT insert the same reference twice using the “Automatic” tab as it will be treated as two separate references. The reference list in this section will be automatically generated and sorted.)

Notes

*Primary authors will typically be those that initially create and complete the content of a page. If a subsequent user modifies the content and feels the effort put forth is of high enough significance to warrant listing in the authorship section, please contact the Associate Editor or other CCGA representative. When pages have a major update by a new author, the new author will be acknowledged at the beginning of the page, and those who contributed previously will be acknowledged below as a prior author. Additional global feedback or concerns are also welcome.

Prior Author(s):