Difference between revisions of "HAEM5:T-prolymphocytic leukaemia"

| [unchecked revision] | [unchecked revision] |

m |

|||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

|} | |} | ||

==Definition / Description of Disease== | ==Definition / Description of Disease== | ||

| − | T-prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) is an aggressive form of T-cell leukemia marked by the proliferation of small to medium-sized prolymphocytes exhibiting a mature post-thymic T-cell phenotype. This condition is characterized by the juxtaposition of TCL1A or MTCP1 genes to a TR locus, typically the TRA/TRD locus. | + | T-prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) is an aggressive form of T-cell leukemia marked by the proliferation of small to medium-sized prolymphocytes exhibiting a mature post-thymic T-cell phenotype. This condition is characterized by the juxtaposition of TCL1A or MTCP1 genes to a TR locus, typically the TRA/TRD locus.<ref name=":5">Elenitoba-Johnson K, et al. T-prolymphocytic leukemia. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Haematolymphoid tumours [Internet]. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024 [cited 2024 June 12]. (WHO classification of tumors series, 5th ed.; vol. 11). Available from: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chaptercontent/63/209</ref> |

==Synonyms / Terminology== | ==Synonyms / Terminology== | ||

T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia | T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia | ||

==Epidemiology / Prevalence== | ==Epidemiology / Prevalence== | ||

| − | T-PLL is | + | T-PLL is an uncommon disease, accounting for approximately 2% of all mature lymphoid leukemias in adults. It mainly affects older individuals, with a median onset age of 65 years, ranging from 30 to 94 years. The disorder exhibits a slight male predominance, with a male to female ratio of 1.33:1.<ref name=":5" /> |

==Clinical Features== | ==Clinical Features== | ||

| − | The most prevalent symptom of the disease is a leukemic presentation, characterized by a rapid, exponential increase in lymphocyte counts, which exceed 100 × 10^9/L in 75% of patients. Approximately 30% of patients may initially experience an asymptomatic, slow-progressing phase, but this typically develops into an active disease state. | + | The most prevalent symptom of the disease is a leukemic presentation, characterized by a rapid, exponential increase in lymphocyte counts, which exceed 100 × 10^9/L in 75% of patients. Approximately 30% of patients may initially experience an asymptomatic, slow-progressing phase, but this typically develops into an active disease state.<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":6" /> |

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|'''Signs and Symptoms''' | |'''Signs and Symptoms''' | ||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

Peripheral blood, bone marrow, spleen (mostly red pulp), liver, lymph node (mostly paracortical), and sometimes skin and serosa (primarily pleura). Extra lymphatic and extramedullary atypical manifestations including skin, muscles and intestines are particularly common in relapse. | Peripheral blood, bone marrow, spleen (mostly red pulp), liver, lymph node (mostly paracortical), and sometimes skin and serosa (primarily pleura). Extra lymphatic and extramedullary atypical manifestations including skin, muscles and intestines are particularly common in relapse. | ||

==Morphologic Features== | ==Morphologic Features== | ||

| − | Blood smears in T-PLL typically reveal anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukocytosis, with atypical lymphocytes in three morphological forms. The most common form (75% of cases) features medium-sized cells with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, moderately condensed chromatin, a single visible nucleolus, and slightly basophilic cytoplasm. In 20% of cases, the cells appear as a small cell variant with densely condensed chromatin and an inconspicuous nucleolus. About 5% of cases exhibit a cerebriform variant with irregular nuclei resembling those in mycosis fungoides. Regardless of the nuclear features, a common morphological characteristic is the presence of cytoplasmic protrusions or blebs.<ref>{{Cite journal|last= | + | Blood smears in T-PLL typically reveal anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukocytosis, with atypical lymphocytes in three morphological forms. The most common form (75% of cases) features medium-sized cells with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, moderately condensed chromatin, a single visible nucleolus, and slightly basophilic cytoplasm. In 20% of cases, the cells appear as a small cell variant with densely condensed chromatin and an inconspicuous nucleolus. About 5% of cases exhibit a cerebriform variant with irregular nuclei resembling those in mycosis fungoides. Regardless of the nuclear features, a common morphological characteristic is the presence of cytoplasmic protrusions or blebs.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Gutierrez|first=Marc|last2=Bladek|first2=Patrick|last3=Goksu|first3=Busra|last4=Murga-Zamalloa|first4=Carlos|last5=Bixby|first5=Dale|last6=Wilcox|first6=Ryan|date=2023-07-28|title=T-Cell Prolymphocytic Leukemia: Diagnosis, Pathogenesis, and Treatment|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37569479|journal=International Journal of Molecular Sciences|volume=24|issue=15|pages=12106|doi=10.3390/ijms241512106|issn=1422-0067|pmc=PMC10419310|pmid=37569479}}</ref>Bone marrow aspirates show clusters of these neoplastic cells, with a mixed pattern of involvement including diffuse and interstitial, in trephine core biopsy.<ref name=":6" /> |

==Immunophenotype== | ==Immunophenotype== | ||

| − | T-cell prolymphocytes show strong staining with alpha-naphthyl acetate esterase and acid phosphatase, presenting a distinctive dot-like pattern, but cytochemistry is not commonly used for diagnosis. | + | T-cell prolymphocytes show strong staining with alpha-naphthyl acetate esterase and acid phosphatase, presenting a distinctive dot-like pattern, but cytochemistry is not commonly used for diagnosis.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Yang|first=K.|last2=Bearman|first2=R. M.|last3=Pangalis|first3=G. A.|last4=Zelman|first4=R. J.|last5=Rappaport|first5=H.|date=1982-08|title=Acid phosphatase and alpha-naphthyl acetate esterase in neoplastic and non-neoplastic lymphocytes. A statistical analysis|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6179423|journal=American Journal of Clinical Pathology|volume=78|issue=2|pages=141–149|doi=10.1093/ajcp/78.2.141|issn=0002-9173|pmid=6179423}}</ref> |

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

|Yes | |Yes | ||

|Yes | |Yes | ||

| − | |These genetic abnormalities serve as diagnostic markers and generally indicate an aggressive disease. This is due to their role in overexpressing oncogenes like TCL1A. | + | |These genetic abnormalities serve as diagnostic markers and generally indicate an aggressive disease. This is due to their role in overexpressing oncogenes like TCL1A. Major diagnostic criteria.<ref name=":6" /> |

|- | |- | ||

|t(X;14)(q28;q11.2) | |t(X;14)(q28;q11.2) | ||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

| | | | ||

|Yes | |Yes | ||

| − | | | + | |Major diagnostic criteria.<ref name=":6" /> |

|} | |} | ||

==Individual Region Genomic Gain / Loss / LOH== | ==Individual Region Genomic Gain / Loss / LOH== | ||

| − | Approximately 70-80% of T-PLL karyotypes are complex, which is considered minor diagnostic criteria, and usually include 3-5 or more structural aberrations. Common cytogenetic abnormalities include those of chromosome 8, such as idic(8)(p11.2), t(8;8)(p11.2;q12), and trisomy 8q. Other frequent changes are deletions in 12p13 and 22q, gains in 8q24 (MYC), and abnormalities in chromosomes 5p, 6, and 17. | + | Approximately 70-80% of T-PLL karyotypes are complex, which is considered minor diagnostic criteria, and usually include 3-5 or more structural aberrations. Common cytogenetic abnormalities include those of chromosome 8, such as idic(8)(p11.2), t(8;8)(p11.2;q12), and trisomy 8q. Other frequent changes are deletions in 12p13 and 22q, gains in 8q24 (MYC), and abnormalities in chromosomes 5p, 6, and 17. A list of clinically significant and/or recurrent CNAs and CN-LOH with potential or strong diagnostic, prognostic and treatment implications in T-PLL |

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

|No | |No | ||

|No | |No | ||

| − | |Recurrent secondary finding (70-80% of cases). Minor diagnostic criteria. <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Staber|first=Philipp B.|last2=Herling|first2=Marco|last3=Bellido|first3=Mar|last4=Jacobsen|first4=Eric D.|last5=Davids|first5=Matthew S.|last6=Kadia|first6=Tapan Mahendra|last7=Shustov|first7=Andrei|last8=Tournilhac|first8=Olivier|last9=Bachy|first9=Emmanuel|date=2019-10-03|title=Consensus criteria for diagnosis, staging, and treatment response assessment of T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31292114|journal=Blood|volume=134|issue=14|pages=1132–1143|doi=10.1182/blood.2019000402|issn=1528-0020|pmc=7042666|pmid=31292114}}</ref> | + | |Recurrent secondary finding (70-80% of cases). Minor diagnostic criteria. <ref name=":6">{{Cite journal|last=Staber|first=Philipp B.|last2=Herling|first2=Marco|last3=Bellido|first3=Mar|last4=Jacobsen|first4=Eric D.|last5=Davids|first5=Matthew S.|last6=Kadia|first6=Tapan Mahendra|last7=Shustov|first7=Andrei|last8=Tournilhac|first8=Olivier|last9=Bachy|first9=Emmanuel|date=2019-10-03|title=Consensus criteria for diagnosis, staging, and treatment response assessment of T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31292114|journal=Blood|volume=134|issue=14|pages=1132–1143|doi=10.1182/blood.2019000402|issn=1528-0020|pmc=7042666|pmid=31292114}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

|5 | |5 | ||

| Line 142: | Line 142: | ||

|Yes | |Yes | ||

|No | |No | ||

| − | |Minor diagnostic criteria | + | |Minor diagnostic criteria. <ref name=":6" /> |

|- | |- | ||

|6 | |6 | ||

| Line 160: | Line 160: | ||

|Yes | |Yes | ||

|Yes | |Yes | ||

| − | |Frequent, Minor diagnostic criteria. | + | |Frequent, Minor diagnostic criteria.<ref name=":6" /> |

|- | |- | ||

|12 | |12 | ||

| Line 169: | Line 169: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |Minor diagnostic criteria | + | |Minor diagnostic criteria.<ref name=":6" /> |

|- | |- | ||

|13 | |13 | ||

| Line 178: | Line 178: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |Minor diagnostic criteria | + | |Minor diagnostic criteria.<ref name=":6" /> |

|- | |- | ||

|17 | |17 | ||

| Line 194: | Line 194: | ||

del(22q) | del(22q) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

22q11-12 <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Stengel|first=Anna|last2=Kern|first2=Wolfgang|last3=Zenger|first3=Melanie|last4=Perglerová|first4=Karolina|last5=Schnittger|first5=Susanne|last6=Haferlach|first6=Torsten|last7=Haferlach|first7=Claudia|date=2014-12-06|title=A Comprehensive Cytogenetic and Molecular Genetic Characterization of Patients with T-PLL Revealed Two Distinct Genetic Subgroups and JAK3 Mutations As an Important Prognostic Marker|url=https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V124.21.1639.1639|journal=Blood|volume=124|issue=21|pages=1639–1639|doi=10.1182/blood.v124.21.1639.1639|issn=0006-4971}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Fang|first=Hong|last2=Beird|first2=Hannah C.|last3=Wang|first3=Sa A.|last4=Ibrahim|first4=Andrew F.|last5=Tang|first5=Zhenya|last6=Tang|first6=Guilin|last7=You|first7=M. James|last8=Hu|first8=Shimin|last9=Xu|first9=Jie|date=2023-09|title=T-prolymphocytic leukemia: TCL1 or MTCP1 rearrangement is not mandatory to establish diagnosis|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37443196|journal=Leukemia|volume=37|issue=9|pages=1919–1921|doi=10.1038/s41375-023-01956-3|issn=1476-5551|pmid=37443196}}</ref> | 22q11-12 <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Stengel|first=Anna|last2=Kern|first2=Wolfgang|last3=Zenger|first3=Melanie|last4=Perglerová|first4=Karolina|last5=Schnittger|first5=Susanne|last6=Haferlach|first6=Torsten|last7=Haferlach|first7=Claudia|date=2014-12-06|title=A Comprehensive Cytogenetic and Molecular Genetic Characterization of Patients with T-PLL Revealed Two Distinct Genetic Subgroups and JAK3 Mutations As an Important Prognostic Marker|url=https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V124.21.1639.1639|journal=Blood|volume=124|issue=21|pages=1639–1639|doi=10.1182/blood.v124.21.1639.1639|issn=0006-4971}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Fang|first=Hong|last2=Beird|first2=Hannah C.|last3=Wang|first3=Sa A.|last4=Ibrahim|first4=Andrew F.|last5=Tang|first5=Zhenya|last6=Tang|first6=Guilin|last7=You|first7=M. James|last8=Hu|first8=Shimin|last9=Xu|first9=Jie|date=2023-09|title=T-prolymphocytic leukemia: TCL1 or MTCP1 rearrangement is not mandatory to establish diagnosis|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37443196|journal=Leukemia|volume=37|issue=9|pages=1919–1921|doi=10.1038/s41375-023-01956-3|issn=1476-5551|pmid=37443196}}</ref> | ||

| Line 203: | Line 201: | ||

| | | | ||

|Leading to the dysregulation of genes such as BCL11B, which is crucial in T-cell development and function.<ref name=":0" /> | |Leading to the dysregulation of genes such as BCL11B, which is crucial in T-cell development and function.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| − | Minor diagnostic criteria | + | Minor diagnostic criteria.<ref name=":6" /> |

|} | |} | ||

==Characteristic Chromosomal Patterns== | ==Characteristic Chromosomal Patterns== | ||

| Line 225: | Line 223: | ||

|} | |} | ||

==Gene Mutations (SNV / INDEL)== | ==Gene Mutations (SNV / INDEL)== | ||

| − | + | Although gene alterations are not yet established as diagnostic criteria and are still under investigation for T-PLL, the mutational landscape of T-PLL reveals significant insights. This landscape highlights the deregulation of DNA repair mechanisms and epigenetic modulators, alongside the frequent mutational activation of the IL2RG-JAK1-JAK3-STAT5B pathway in the pathogenesis of T-PLL. These discoveries open up potential avenues for novel targeted therapies in treating this aggressive form of leukemia.<ref name=":3" /> | |

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 370: | Line 368: | ||

[[Category:DISEASE]] | [[Category:DISEASE]] | ||

[[Category:Diseases T]] | [[Category:Diseases T]] | ||

| − | |||

Revision as of 16:18, 12 June 2024

Haematolymphoid Tumours (5th ed.)

| This page is under construction |

(General Instructions – The main focus of these pages is the clinically significant genetic alterations in each disease type. Use HUGO-approved gene names and symbols (italicized when appropriate), HGVS-based nomenclature for variants, as well as generic names of drugs and testing platforms or assays if applicable. Please complete tables whenever possible and do not delete them (add N/A if not applicable in the table and delete the examples); to add (or move) a row or column to a table, click nearby within the table and select the > symbol that appears to be given options. Please do not delete or alter the section headings. The use of bullet points alongside short blocks of text rather than only large paragraphs is encouraged. Additional instructions below in italicized blue text should not be included in the final page content. Please also see Author_Instructions and FAQs as well as contact your Associate Editor or Technical Support)

Primary Author(s)*

Parastou Tizro, MD, Celeste Eno, PHD, Sumire Kitahara, MD

WHO Classification of Disease

(Will be autogenerated; Book will include name of specific book and have a link to the online WHO site)

| Structure | Disease |

|---|---|

| Book | |

| Category | |

| Family | |

| Type | |

| Subtype(s) |

Definition / Description of Disease

T-prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) is an aggressive form of T-cell leukemia marked by the proliferation of small to medium-sized prolymphocytes exhibiting a mature post-thymic T-cell phenotype. This condition is characterized by the juxtaposition of TCL1A or MTCP1 genes to a TR locus, typically the TRA/TRD locus.[1]

Synonyms / Terminology

T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Epidemiology / Prevalence

T-PLL is an uncommon disease, accounting for approximately 2% of all mature lymphoid leukemias in adults. It mainly affects older individuals, with a median onset age of 65 years, ranging from 30 to 94 years. The disorder exhibits a slight male predominance, with a male to female ratio of 1.33:1.[1]

Clinical Features

The most prevalent symptom of the disease is a leukemic presentation, characterized by a rapid, exponential increase in lymphocyte counts, which exceed 100 × 10^9/L in 75% of patients. Approximately 30% of patients may initially experience an asymptomatic, slow-progressing phase, but this typically develops into an active disease state.[1][2]

| Signs and Symptoms | B symptoms (Fever, night sweats, weight loss)

Hepatosplenomegaly (Frequently observed) Generalized lymphadenopathy with slightly enlarged lymph nodes (Frequently observed) Cutaneous involvement (20%) Malignant effusions (15%) Asymptomatic and indolent phase (30% of cases) |

| Laboratory Findings | Anemia and thrombocytopenia

Marked lymphocytosis > 100 × 10^9/L (75% of cases) Atypical lymphocytosis > 5 × 10^9/L Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (increased-may reflect disease burden) β 2 microglobulin (B2M) (increased-may reflect disease burden) |

Sites of Involvement

Peripheral blood, bone marrow, spleen (mostly red pulp), liver, lymph node (mostly paracortical), and sometimes skin and serosa (primarily pleura). Extra lymphatic and extramedullary atypical manifestations including skin, muscles and intestines are particularly common in relapse.

Morphologic Features

Blood smears in T-PLL typically reveal anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukocytosis, with atypical lymphocytes in three morphological forms. The most common form (75% of cases) features medium-sized cells with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, moderately condensed chromatin, a single visible nucleolus, and slightly basophilic cytoplasm. In 20% of cases, the cells appear as a small cell variant with densely condensed chromatin and an inconspicuous nucleolus. About 5% of cases exhibit a cerebriform variant with irregular nuclei resembling those in mycosis fungoides. Regardless of the nuclear features, a common morphological characteristic is the presence of cytoplasmic protrusions or blebs.[3]Bone marrow aspirates show clusters of these neoplastic cells, with a mixed pattern of involvement including diffuse and interstitial, in trephine core biopsy.[2]

Immunophenotype

T-cell prolymphocytes show strong staining with alpha-naphthyl acetate esterase and acid phosphatase, presenting a distinctive dot-like pattern, but cytochemistry is not commonly used for diagnosis.[4]

| Finding | Marker |

|---|---|

| Positive (universal) | cyTCL1 (highest specificity), CD2, CD3 (may be weak), CD5, CD7 (strong), TCR-α/β, S100 (30% of cases) |

| Positive (subset) | CD4 (in some cases CD4+/CD8+ or CD4-/CD8+), CD52 (therapeutic target), activation markers are variable (CD25, CD38, CD43, CD26, CD27) |

| Negative (universal) | TdT, CD1a, CD57, CD16, HTLV1 |

| Negative (subset) | CD8 (in some cases CD4+/CD8+ or CD4-/CD8+) |

Chromosomal Rearrangements (Gene Fusions)

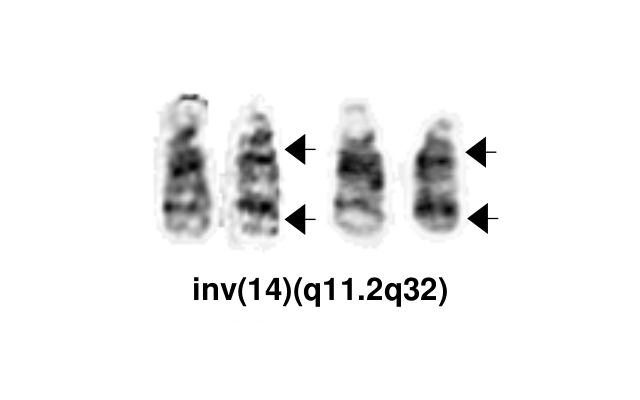

Rearrangements involving the TCL1 (T-cell leukemia/lymphoma1) family genes—TCL1A, MTCP1 (mature T-cell proliferation), or TCL1B (also known as TCL1/MTCP1-like 1 [TML1])—are relatively specific to T-PLL. These are present in more than 90% of cases, either as inv(14)(q11q32) or t(14;14)(q11;q32) (involving TCL1A or TCL1B), or t(X;14)(q28;q11) (involving MTCP1). T-PLL-ISG).

| Chromosomal Rearrangement | Genes in Fusion (5’ or 3’ Segments) | Pathogenic Derivative | Prevalence | Diagnostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Prognostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Therapeutic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inv(14)(q11.2q32.1)

t(14;14)(q11.2;q32.1) |

TCL1A/B ,TRD | inv(14) ~60%

t(14;14) ~25% |

Yes | Yes | Yes | These genetic abnormalities serve as diagnostic markers and generally indicate an aggressive disease. This is due to their role in overexpressing oncogenes like TCL1A. Major diagnostic criteria.[2] | |

| t(X;14)(q28;q11.2) | MTCP1, TRD | Low (5%) | Yes | Major diagnostic criteria.[2] |

Individual Region Genomic Gain / Loss / LOH

Approximately 70-80% of T-PLL karyotypes are complex, which is considered minor diagnostic criteria, and usually include 3-5 or more structural aberrations. Common cytogenetic abnormalities include those of chromosome 8, such as idic(8)(p11.2), t(8;8)(p11.2;q12), and trisomy 8q. Other frequent changes are deletions in 12p13 and 22q, gains in 8q24 (MYC), and abnormalities in chromosomes 5p, 6, and 17. A list of clinically significant and/or recurrent CNAs and CN-LOH with potential or strong diagnostic, prognostic and treatment implications in T-PLL

| Chr # | Gain / Loss / Amp / LOH | Minimal Region Genomic Coordinates [Genome Build] | Minimal Region Cytoband | Diagnostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Prognostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Therapeutic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | Gain | idic(8)(p11)

t(8;8)(p11;q12) trisomy 8q |

idic(8)(p11.2)

t(8;8)(p11.2;q12) trisomy 8q |

Yes | No | No | Recurrent secondary finding (70-80% of cases). Minor diagnostic criteria. [2] |

| 5 | Abnormality | 5p, 5q[5] | Yes | Yes | No | Minor diagnostic criteria. [2] | |

| 6 | Abnormality | 6p | No | ||||

| 11 | Loss | 11q | ch11q21-q23.3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Frequent, Minor diagnostic criteria.[2] |

| 12 | Loss | 12p | 12p13 | Yes | Minor diagnostic criteria.[2] | ||

| 13 | Loss | 13q | 13q14.3 | Yes | Minor diagnostic criteria.[2] | ||

| 17 | Abnormality | 17p, 17q | 17p13 | Yes | Yes (resistance to therapy) | ||

| 22 | Loss | Monosomy 22

del(22q) |

(most common) |

Leading to the dysregulation of genes such as BCL11B, which is crucial in T-cell development and function.[7]

Minor diagnostic criteria.[2] |

Characteristic Chromosomal Patterns

| Chromosomal Pattern | Diagnostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Prognostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Therapeutic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| inv(14)(q11q32)

t(14;14)(q11.2;q32.1) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | EXAMPLE:

See chromosomal rearrangements table as this pattern is due to an unbalanced derivative translocation associated with oligodendroglioma (add reference). |

Gene Mutations (SNV / INDEL)

Although gene alterations are not yet established as diagnostic criteria and are still under investigation for T-PLL, the mutational landscape of T-PLL reveals significant insights. This landscape highlights the deregulation of DNA repair mechanisms and epigenetic modulators, alongside the frequent mutational activation of the IL2RG-JAK1-JAK3-STAT5B pathway in the pathogenesis of T-PLL. These discoveries open up potential avenues for novel targeted therapies in treating this aggressive form of leukemia.[8]

| Gene; Genetic Alteration | Presumed Mechanism (Tumor Suppressor Gene [TSG] / Oncogene / Other) | Prevalence (COSMIC / TCGA / Other) | Concomitant Mutations | Mutually Exclusive Mutations | Diagnostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Prognostic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Therapeutic Significance (Yes, No or Unknown) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATM | TSG | 53% (COSMIC) | ATM mutation/deletion | None specified | Yes | Yes | Yes (PARP inhibitors, NCT03263637) | Deletions of or missense mutations at the ATM locus are found in up to 80% to 90% of T-PLL cases. (T-PLL-ISG). |

| FBXW10 | TSG | 72% (COSMIC) | JAK/STAT pathway | None specified | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | |

| IL2RG, JAK1, JAK3, STAT5B | Oncogene | 8% JAK1

34% JAK3 16% STAT5B 2% IL2RG (COSMIC) |

ATM, TP53, Epigenetic modifiers [9][10] | Typically, mutations within this pathway occur in a mutually exclusive manner.[8] | Yes | Yes | The cumulative prevalence of these mutations in T-PLL is approximately 60%. (Dr jaffe book) | |

| EZH2 | Oncogene, TSG | 16% (COSMIC) | JAK/STAT pathway[9][10] | None specified | No | Yes | See note | EZH2 inhibitors like tazemetostat have shown efficacy in other hematologic malignancies, providing a rationale for their potential use in T-PLL |

| BCOR | TSG | 8% (COSMIC) | JAK/STAT pathway[9][10] | None specified | No | Yes | Yes?? | |

| SAMHD1 | TSG | ~7-20%[11][12] | None specified | Yes | SAMHD1 mutations may indicate a defective DNA damage response and aggressive disease [11] | |||

| CHEK2 | TSG | 5% (COSMIC) | ATM, TP53, JAK/STAT pathway, Epigenetic modifiers | None specified | No | Yes | No | CHEK2 mutations may indicate a defective DNA damage response and aggressive disease [8][13] |

| TP53 | TSG | 2% (COSMIC) | ATM, JAK/STAT pathway, Epigenetic modifiers | None specified | No | Yes | Associated with resistance to therapy | Mutations in TP53 are less frequent than deletions[14] |

Note: A more extensive list of mutations can be found in cBioportal (https://www.cbioportal.org/), COSMIC (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), ICGC (https://dcc.icgc.org/) and/or other databases. When applicable, gene-specific pages within the CCGA site directly link to pertinent external content.

Epigenomic Alterations

Research indicates that epigenetic modifications in the regulatory regions of key oncogenes and genes involved in DNA damage response and T-cell receptor regulation are clearly present. These changes are closely associated with the transcriptional dysregulation that forms the core lesions of T-PLL.[15]

Genes and Main Pathways Involved

Put your text here and fill in the table (Instructions: Can include references in the table. Do not delete table.)

| Gene; Genetic Alteration | Pathway | Pathophysiologic Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| TCL1A/B rearrangement | AKT signaling and TCR signal amplification pathways | Increased cell survival and proliferation |

| MTCP1 | AKT signaling and TCR signal amplification pathways | Increased cell survival and proliferation |

| ATM, CHEK2 | DNA damage repair pathway | Genomic instability |

| JAK1, JAK3, STAT5B | JAK-STAT pathway | Unchecked cell growth and survival |

| IL2RG | JAK-STAT pathway, Cytokine signaling | Promoting lymphocyte proliferation |

| EZH2 | Transcription regulator | Altering the epigenetic landscape |

Genetic Diagnostic Testing Methods

Cytogenetics (FISH, CpG-stimulated Karyotype, SNP microarray), PCR for TRB/TRG and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). The genetic diagnostic process involves detecting clonal rearrangements of the TR gene and rearrangements of the TCL1 gene at the TRB or TRG loci.

Familial Forms

There is no noticeable familial clustering. However, a subset of cases may develop in the context of ataxia-telangiectasia (AT), which is characterized by germline mutations in the ATM gene. Here there is a combined heterozygosity in the form of biallelic inactivating mutations of the ATM tumor suppressor gene.[16] Penetrance of the tumor phenotype is about 10% to 15% by early adulthood.[17] It represents nearly 3% of all malignancies in patients with ataxia-telangiectasia.[18]

Additional Information

In T-PLL, the rapid growth of the disease necessitates immediate initiation of treatment. The most effective first-line treatment is alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 antibody with remission rates over 80%. However, these remissions usually last only 1-2 years. To potentially extend remission, eligible patients are advised to undergo allogeneic blood stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) during their first complete remission, which can lead to longer remission durations of over 4-5 years for 15-30% of patients. Consequently, the prognosis for T-PLL remains poor, with median overall survival times under two years and five-year survival rates below 5%. Ongoing research is exploring molecularly targeted drugs and signaling pathway inhibitors, for routine clinical use in treating T-PLL.

Links

(use the "Link" icon that looks like two overlapping circles at the top of the page) (Instructions: Highlight text to which you want to add a link in this section or elsewhere, select the "Link" icon at the top of the page, and search the name of the internal page to which you want to link this text, or enter an external internet address by including the "http://www." portion.)

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 Elenitoba-Johnson K, et al. T-prolymphocytic leukemia. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Haematolymphoid tumours [Internet]. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024 [cited 2024 June 12]. (WHO classification of tumors series, 5th ed.; vol. 11). Available from: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chaptercontent/63/209

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Staber, Philipp B.; et al. (2019-10-03). "Consensus criteria for diagnosis, staging, and treatment response assessment of T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia". Blood. 134 (14): 1132–1143. doi:10.1182/blood.2019000402. ISSN 1528-0020. PMC 7042666 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 31292114. - ↑ Gutierrez, Marc; et al. (2023-07-28). "T-Cell Prolymphocytic Leukemia: Diagnosis, Pathogenesis, and Treatment". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 24 (15): 12106. doi:10.3390/ijms241512106. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC PMC10419310 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 37569479 Check|pmid=value (help).CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ↑ Yang, K.; et al. (1982-08). "Acid phosphatase and alpha-naphthyl acetate esterase in neoplastic and non-neoplastic lymphocytes. A statistical analysis". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 78 (2): 141–149. doi:10.1093/ajcp/78.2.141. ISSN 0002-9173. PMID 6179423. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Tirado, Carlos A.; et al. (2012-08-20). ""T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL), a heterogeneous disease exemplified by two cases and the important role of cytogenetics: a multidisciplinary approach"". Experimental Hematology & Oncology. 1 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/2162-3619-1-21. ISSN 2162-3619. PMC 3514161. PMID 23211026.

- ↑ Stengel, Anna; et al. (2014-12-06). "A Comprehensive Cytogenetic and Molecular Genetic Characterization of Patients with T-PLL Revealed Two Distinct Genetic Subgroups and JAK3 Mutations As an Important Prognostic Marker". Blood. 124 (21): 1639–1639. doi:10.1182/blood.v124.21.1639.1639. ISSN 0006-4971.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Fang, Hong; et al. (2023-09). "T-prolymphocytic leukemia: TCL1 or MTCP1 rearrangement is not mandatory to establish diagnosis". Leukemia. 37 (9): 1919–1921. doi:10.1038/s41375-023-01956-3. ISSN 1476-5551. PMID 37443196 Check

|pmid=value (help). Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Kiel, Mark J.; et al. (2014-08-28). "Integrated genomic sequencing reveals mutational landscape of T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia". Blood. 124 (9): 1460–1472. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-03-559542. ISSN 1528-0020. PMC 4148768. PMID 24825865.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 Andersson, E. I.; et al. (2018-03). "Discovery of novel drug sensitivities in T-PLL by high-throughput ex vivo drug testing and mutation profiling". Leukemia. 32 (3): 774–787. doi:10.1038/leu.2017.252. ISSN 1476-5551. PMID 28804127. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 Pinter-Brown, Lauren C. (2021-12-30). "JAK/STAT: a pathway through the maze of PTCL?". Blood. 138 (26): 2747–2748. doi:10.1182/blood.2021014238. ISSN 0006-4971.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Johansson, Patricia; et al. (2018-01-19). "SAMHD1 is recurrently mutated in T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia". Blood Cancer Journal. 8 (1): 11. doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0036-5. ISSN 2044-5385. PMC 5802577. PMID 29352181.

- ↑ Schrader, A.; et al. (2018-02-15). "Actionable perturbations of damage responses by TCL1/ATM and epigenetic lesions form the basis of T-PLL". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 697. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02688-6. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5814445. PMID 29449575.

- ↑ Braun, Till; et al. (2021). "Advanced Pathogenetic Concepts in T-Cell Prolymphocytic Leukemia and Their Translational Impact". Frontiers in Oncology. 11: 775363. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.775363. ISSN 2234-943X. PMC 8639578 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 34869023 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Stengel, Anna; et al. (2016-01). "Genetic characterization of T-PLL reveals two major biologic subgroups and JAK3 mutations as prognostic marker". Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer. 55 (1): 82–94. doi:10.1002/gcc.22313. ISSN 1098-2264. PMID 26493028. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Tian, Shulan; et al. (2021-04-15). "Epigenetic alteration contributes to the transcriptional reprogramming in T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 8318. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87890-9. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8050249 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 33859327 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Suarez, Felipe; et al. (2015-01-10). "Incidence, presentation, and prognosis of malignancies in ataxia-telangiectasia: a report from the French national registry of primary immune deficiencies". Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 33 (2): 202–208. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.56.5101. ISSN 1527-7755. PMID 25488969.

- ↑ Taylor, A. M.; et al. (1996-01-15). "Leukemia and lymphoma in ataxia telangiectasia". Blood. 87 (2): 423–438. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 8555463.

- ↑ Li, Geling; et al. (2017-12-26). "T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia in an adolescent with ataxia-telangiectasia: novel approach with a JAK3 inhibitor (tofacitinib)". Blood Advances. 1 (27): 2724–2728. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2017010470. ISSN 2473-9529. PMC 5745136. PMID 29296924.

Notes

*Primary authors will typically be those that initially create and complete the content of a page. If a subsequent user modifies the content and feels the effort put forth is of high enough significance to warrant listing in the authorship section, please contact the CCGA coordinators (contact information provided on the homepage). Additional global feedback or concerns are also welcome.